Military history is an essential part of the traditions that are the key to what keeps the armed forces of any country closely knit and tells the coming generations to go beyond their call of duty. India’s military history is indeed remarkable, and has been a source of pride and inspiration for many regiments of the Indian army first, and later the two sister services.

Until 1947, our men fought under the flag of the Empire, but as a part of Indian regiments and were Indians in as much as an Indian soldier is today. To question their loyalties is to question the many traditions that are revered by so many of our units and regiments. They fought for Naam (of their Regiment or Unit) and Nishan (the Flags they carried into battles). Many of their tales of gallantry have been beautifully narrated by Philip Mason in his remarkable book: ‘A Matter of Honour’.

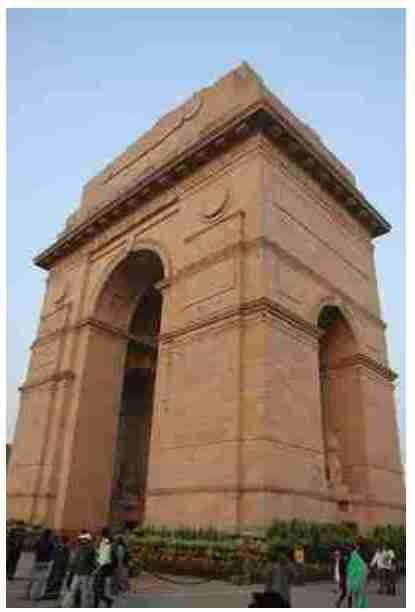

In the first World War (1914-18) over a million Indian soldiers were deployed against the German empire, of whom over 74,000 Indian soldiers died, and some 67,000 were wounded. And while the role of the Australians, New Zealanders, Canadians and South Africans have been remembered and even immortalised in films, the role of the tough but silent 1.3 million Indian soldiers has generally been ignored, but for the Salute to their sacrifices erected in the form of India Gate in Delhi, by the British leadership in India, after the war.

It was thus annoying to learn of the current Indian government’s decision to order the armed forces to shift the flame of the Amar Jawan – set to burn eternally under the India gate – to the new war memorial complex, adjacent to it. This led to a controversy, with a few of us, insisting that the military’s leadership had let down those who had died in the Great War, in the line of duty.

Apologists from the services – both, serving and retired – had argued that the shifting of the eternal flame – that was lit in memory of those who fell in the 1971 war – was being done to integrate all memorials in one place. If so, what should be the significance of the Teen Murti memorial or the Battle Honours army mess, or others elsewhere, hereafter?

The question is, can we so easily erase the memories associated with the India Gate, since successive prime ministers and other dignitaries have paid respects there, specially over nearly 50 Republic Days?

More so, as it had come to be associated by the public – that regularly flocked near it – as a connection with our brave hearts, even if they had fallen for the empire, with their names etched on India Gate or as was symbolised by the flame near the helmet atop the rifle of an unknown soldier who fell in the 1971 Indo-Pak war. Our military men often complain of the absence of a connection with the public, and when we had one, they’ve chosen to disconnect, in keeping with apparently a political diktat!

The question is, can we so easily erase the memories associated with the India Gate, since successive prime ministers and other dignitaries have paid respects there, specially over nearly 50 Republic Days?

It has been suggested that the decision to shift the eternal flame to the new National War Memorial – that was inaugurated in 2019 by the Prime Minister weeks before the last parliamentary elections – was to draw the focus of attention to the new War Memorial. It’s no doubt an impressive complex of murals and names of our post-independence wars.

But it could have been integrated with the India Gate, more so, as there is going to be a statue of Netaji SC Bose in between the two memorials. And, it is also worth mentioning here that there isn’t any mention in the memorial complex or a roll of honour of our gallant men who died in World War- II, which at its height saw more than 2.5 million India troops fighting across the globe. They, like those who fought and died in World War-I, were also Indians, and deserve our salutations.