Man, at times of his necessity for the good and for bad at times of war, used his brethren, his menials, slaves and even the quadruped animals and biped-birds too. But, a war between countries, gets all of them into action, leading to someone’s victory and huge loss of life for both the winner and the vanquished. There are no family members to cry for the animals, unlike the humans.

While the statistics on total soldiers killed in different wars are available, the data for non-humans killed in famous wars is rather sketchy. It is reported that sixteen million animals served in the armies of the first world war. Horses, elephants, camels, and other animals have been used for both transportation and mounted attack.

The Royal Society for Prevention of Cruelty to Animals estimates that 484,143 horses, mules, camels and bullocks were killed in British War service between 1914 and 1918. These animals had no voice and their ‘silent’ sacrifice is absolutely forgotten. On Veterans Day, all the soldiers are remembered, but, very few ever remember the service that these animals gave to their masters.

There are a few memorials for some canines and equines, but rarely for the rest such as the mules, bullocks, elephants and other pack animals. The birds who rendered great service in war are also scantily remembered.

In the First World War, Sinai/Mesopotamia campaigns, the ‘higher’ follower category of the non-combatant army personnel were the drivers of packed and wheeled transports with mules, bullocks and camels in the Supply and Transport Corps. There were separate Mule Corps, Bullock Corps and Camel Corps with mentions of various depot numbers.

There were two categories of followers viz.” public” and “private”. Public followers were paid by the government and private followers were paid by regiments. There were about 20,000 personnel in the three animal transport corps.

Horses

Horses and mules are the most commonly used animals in wars. Horses for mounted cavalry charges and mules as beasts of burden, for transporting goods to different areas.

Some 2,700 of 94,000 horses sent from USA to western war front, sank and died in a submarine attack on the animals transport ship, much before seeing action. By August 1917, the British Army had 368,000 horses and 82,000 mules in Belgium and France.

On Veterans Day, all the soldiers are remembered, but, very few ever remember the service that these animals gave to their masters.

By the end of the war most horses, as well as mules, were pulling gun limbers, ammunition trains, supply wagons and ambulances.Horse-drawn ambulances, though slow, were the most suitable in the front where the ground was full of craters and where the conventional motor ambulances could not be effectively used. Horses, mules, and dogs when injured were moaning and groaning in high pitch which was unbearable to the human ears. These animals, like soldiers, were hit by shells, bullets and shrapnels, and also poison gas.

There were numerous deaths of these animals by disease and wounds rather than direct bullets. Many a time, the horse was more valuable than a soldier. As these animals were taken right up to the war front, the animal deaths were also more. There was no “Horse Corps”.

Probably the Veterinary Corps would have directly taken charge of the horses. The last cavalry charge using horses took place in September 1918, when the Jodhpur Lancers, one of India’s elite cavalry regiments, attacked German and Turkish defences in the Mediterranean town of Haifa and won a great battle.

Mules

Mules were used by the British, American and Indian Armies, during World War I and II to carry supplies and equipment over difficult terrain. These pack animals are innately patient, cautious, and hardy. Mules could carry heavy loads of supplies where Jeeps and even pack horses could not travel. Mules were used in the Palestine, Sinai and Mesopotamian areas of WW I and in North Africa, Burma and Italy in WW II. They were also used for transporting supplies in mountainous regions.

In the Mule Corps of WW I, Palestine/Sinai/Mesopotamia sector, there were around 50 depots. They were numbered between 1 to 75, with some numbers missing in between. Some depots also were numbered with alphabets, such as‘A Depot’, ‘B Depot’, ‘C Complement’, ‘CB Depot’, ‘CC Rawalpindi’, Base Transport Depot (Field Section), etc. The number of animals in each depot is not known. In the Mule Corps which served in Mesopotamia, the soldiers Killed in Action (KIA) who belonged to these depots, are listed in the Basra Memorial.

Dogs

The dogs were land messengers to carry information while moving around trenches and battle areas, with canine expertise. Dogs have long been employed in a wide variety of military purposes, more recently focusing on guarding and bomb detection. They worked with their keen sense of smell and hearing, to locate wounded, immobile soldiers from trenches, and their companionship was invaluable. Like the Americans, British Forces also used dogs as mascots of their units.

The Germans had a force of 30,000 dogs, recruited for war purposes. They hunted for rats in trenches. They carried messages, food to some wounded soldiers, and did “mercy service” by staying with dying soldiers. They carried urgent messages in the tough forward areas. They were also used to lay communication lines. They pulled machine guns in the field. A post mortem of a dog named Dick showed shrapnel near his spine and a bullet in his chest, and he was in service till his death. “I have given my husband and my sons,” wrote one English woman, “and now that he too is required, I give my dog.” That must have been terrible for the lonely lady.

“Stubby” was a terrier pup of Private Robert Conroy of Britain who took it to France in his posting. Stubby had learnt the drills, calls, the salutes and was the mascot of 102nd Infantry of 26th Yankee Division. He used to give early warning barking in cases of enemy gassing, thereby saving many lives. He was also used for searching and finding lost soldiers in the front. In one instance, he was able to catch a German spy and consequently was promoted to the rank of Sergeant!

He was wounded in battle when he was hit by shrapnel and was hospitalised, but in hospital too, he cheered the wounded soldiers. Stubby received many awards in the 17 battles that he took part in.

Camels

Camels were first mentioned as being used in warfare sometime around 853 BCE. They were used extensively in both the World Wars as mounts in arid regions. They formed the Camel Cavalry, being better able to traverse sandy deserts than horses, and requiring far less water. In WW I, camels were of great use in the Sinai and Mesopotamia. During this war, there were seven depots of the Camel Corps, viz. the 3rd, 6th (Government Depot), 65th, 70th, 71st, Central Personnel Depot and the Indian Medical Service Depot. The number of camels in each depot does not find mention. The soldiers of the Camel Corps, KIA find mention in the Basra memorial.

Camels were also used by the Indian Army. The Camel tradition in India dates back to the time of Maharaja Rao Jodha of Jodhpur in the fifteenth century. When India became independent, the camel regiments of the Rajasthan region merged with that of the Indian Army. The Army used camels in both the 1948 and 1965 wars with Pakistan. After that, they were handed over to the BSF, who used the camels effectively in the 1971 war with Pakistan. As of now, the BSF uses camels for patrolling in the desert regions of Rajasthan.

Elephants

While elephants are not considered domesticable, they can be trained to serve as mounts, or for moving heavy loads. Sanskrit hymns record their use for military purposes as early as 1,100BCE A group of elephants was employed by Hannibal during the Second Punic War. They were employed as recently as in WW I by the British by both the Japanese and Allies in WW II.

It was reported that a few elephants in zoos and circus companies in Britain were conscripted for army service, within Britain. Elephants could perform the work of machines in locations where vehicles could not penetrate, so they found use in the Burma Campaign WWII.

Bullocks

Bullocks were used to haul transports in various sectors of World War I. The Bullock Corps of WW I had depots in Palestine/Sinai/Mesopotamia sector. These were the 1st(Lucknow),2nd, 4th,38th (half troop) attd Pontoon sec; 46th (half troop), 51st (half troop); 57th (half troop);58th, 61st, 67th and “C B” Depot. The soldiers KIA in these depots are commemorated in the Basra Memorial.

Pigeons

It is estimated that around 100,000 pigeons were used for carrying messages to soldiers behind enemy lines. They were kept in special cages and protected well. Their homing capability was used to the full. The army division HQ kept pigeon lofts and they used to get message carrying pigeon from the front on to the lofts.

In the field, soldiers used to carry mobile lofts, throughout their working areas. “Peerless Pilot” a pigeon of US forces delivered 196 messages, from the sea to the base. “Gay-Neck” was a trained carrier pigeon from India, to serve in France during WW1to carry messages of courage and hope.

The pigeon returned home as a hero and was immortalised by Dhan Gopal Mukerji in his book, Gay-Neck: The story of a Pigeon. Another war service pigeon, Cher Ami, carried messages and though shot and injured, saved 200 US soldiers of the “Lost Battalion,” who were behind the enemy lines. France honoured this pigeon with the “Croix de Guerre”.Around 20,000 pigeons died in service in World War I

Other living creatures

It may come us a surprise to some that slugs were used in WW I to detect mustard gas. In the battlefield, the slugs would visibly indicate their discomfort by closing their breathing pores and compressing their bodies in the presence of mustard gas. This gave soldiers in the trenches enough time to put on their gas masks to protect themselves from harmful levels of gas, saving many lives. Rats and pigs were also used in the Wars. One South African unit had a baboon called “Jackie” with sharp hearing, who would tug at men’s sleeves if he detected enemy advances.

Donkeys, pigs and magpies were used to give company to soldiers who had mortar shell shocks and the stress of war. Even cats were used as mascots and pets of soldiers and to hunt for rats in the trenches. Whales found themselves on the wing end of the stick as they were killed and processed for glycerine, for making bombs, rifle oil, fuel for stoves used in trenches and to treat trench foot. Around 175,000 whales were killed in the south Atlantic sea.

Veterinary services

Army Veterinary Corps did yeoman service in administering veterinary medicine and evacuation of the injured. Mobile veterinary service with evacuation stations cared for extensive emergency care in horse-drawn ambulances, or motor ambulances taking two animals at a time and in trains available at nearby railheads.

The watering and feeding of these injured animals were taken care of. Veterinary Hospitals cared for 2500 to 3500 animals per week. Between 18 August 1914 and 23 January 1919 over half a million sick and wounded animals passed through the British Army’s Mobile Veterinary Sections and Veterinary Evacuating Stations in Flanders and France.

In response to the military importance of horses and mules, the (Royal) Army Veterinary Corps established a system of veterinary medicine parallel to the casualty evacuation system of the Royal Army Medical Corps. The equivalent of the Field Ambulance was the Mobile Veterinary Section; animals needing more extensive emergency care were transferred to Veterinary Evacuation Stations (the equivalent of the Casualty Clearing Station) located at railheads.

They were moved either by horse-drawn ambulance or by special motor ambulances designed to carry two horses each. Like wounded soldiers, horses needing further medical or surgical attention were transported by barges or by rail to veterinary hospitals at the base on the French coast. Once the Veterinary Evacuating Stations had been established, special horse trains were introduced.

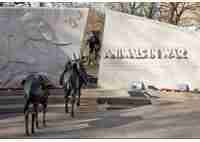

Memorials and decorations

The only famous memorial for “Animals in War” in Park Lane, London, has bronze mules, a bronze horse and a dog. Images of other animals used and lost in the war are sculpted in bas-relief on the walls, amongst them being a cat named Simon, a pigeon called GI Joe, a war dog called Rob, a police horse called Upstart and many others.

Warhorse “Blackie’s” grave in Liverpool, “Songster” the horse’s memorial at Loughborough, for the British Empire’s horses which fell in WW1, “Animals in War” (AIW) memorial at Hampstead Suburb of London, the Tunnellers Friends memorial for the Canaries and mice at Edinburgh, Scotland; Pigeons Memorial at Lille, France, are the other famous ones.

A medal called the PDSA Dickin Medal recognised as the animals Victoria Cross was instituted to recognise animal bravery. The medal was named after Maria Dickin, the founder of the PDSA (People’s Dispensary for Sick Animals). Between 1943 and 1949, 54 animals received the medal, including 32 pigeons, 18 dogs and 3 horses.