“May I have a light?” I looked up to see a Japanese – more or less my age – with an unlit cigarette in his hand. I reached for my lighter. He lit up. We were on a train travelling from Berne to Geneva in the autumn of 1980. “Indian?” he asked. “Yes” I replied. We got talking. He was an official in the UN and was returning to home and headquarters at Geneva. I was scheduled to lecture at the university. We chit-chatted for a while; he gave me some useful tips on what to see and where to eat in the city. Then, having exhausted the store of ‘safely tradable information’, we fell silent. I retrieved my book – ‘Defeat into Victory’, an account of the Second World War in Burma by Field Marshal William Slim. He opened the newspaper. We traveled in silence. After a while he asked “Are you a professor of Military History?” “No” I replied- “just interested. My father was in Burma during the war”. “Mine too” he said.

In December 1941, Japan invaded Burma and opened the longest land campaign of the entire war for Britain. There were two reasons for the Japanese invasion. First, cutting the overland supply route to China via the Burma Road would deprive Chiang Kaishek’s Nationalist Chinese armies of military equipment and pave the way for the conquest of China. Second, possession of Burma would position them at the doorway to India, where they believed a general insurrection would be triggered against the British once their troops established themselves within reach of Calcutta. Entering Burma from Thailand, the Japanese quickly captured Rangoon in 1942, cut off the Burma Road at source and deprived the Chinese of their only convenient supply base and port of entry. Winning battle after battle, they forced theallied forces to retreat into India. The situation was bleak. The British were heavily committed to the war in Europe and lacked the resources and organisation to recapture Burma. However, by1943 they got their act together. The High Command was overhauled; Wavell was replaced by Mountbatten and operational control was given to General William Slim, a brilliant officer. Slim imbued his men with a new spirit, rebuilt morale and forged the famous 14th Army, an efficient combat force made up of British, Indians and Africans. The Japanese, aware that the defenders were gathering strength, resolved to end the campaign with a bold thrust into India and a simultaneous attack in the Arakan in Burma.

In the ebb and flow of these large events chronicled in Military History, my father, a soldier, played a part — first in Kohima in clearing the Japanese from the Naga Hills, then in Imphal and finally in the deeply forested mountains of Arakan. Destiny took him there. In the blinding rain of the monsoons in 1943, the Supreme Allied Commander’s plane landed at Maugdow where the All-India Brigade of which his regiment was a part was headquartered. Mountbatten was accompanied by his Chief of Staff, Lt. Gen. Browning, who had been my father’s Adjutant at the Royal Military College in Sandhurst. He and the two other Indian commanders—Thimayya and Sen— were introduced to Mountbatten who made casual but searching enquiries regarding their war experience. IN DECEMBER 1941, JAPAN INVADED BURMA AND OPENED THE LONGEST LAND CAMPAIGN OF THE ENTIRE WAR FOR BRITAIN. THERE WERE TWO REASONS FOR THE JAPANESE INVASION. FIRST, CUTTING THE OVERLAND SUPPLY ROUTE TO CHINA VIA THE BURMA ROAD WOULD DEPRIVE CHIANG KAI-SHEK’S NATIONALIST CHINESE ARMIES OF MILITARY EQUIPMENT AND PAVE THE WAY FOR THE CONQUEST OF CHINA.

Thereafter he was closeted in the ‘conference tent’ with the senior commanders for a long time. As they came out he turned to Reggie Hutton, the Brigade commander and said, “All right Reggie let your All-Indian Brigade do it. But, by God, it is going to be tough”. Then, turning to the three of them he said, “Gentlemen, the Japanese are pulling out of upper Burma. You have been selected to intercept their withdrawal from there into the South. You will concentrate at Akyab, proceed to Myebon by sea, capture Kangaw, penetrate Japanese-held territory and convert the Japanese retreat into a rout. Is that clear?” It was.

My Japanese friend who had been listening intently leaned forward and asked “Did you say your father was in the All India Brigade?” “Yes”, I replied. Our conversation paused for a while as the waiter served coffee and croissants. Later, picking up the threads he persisted “Was he a junior officer at the time?” “Not really” I replied. “He was a battalion commander”. He digested the information and said “Which regiment?” “The Punjab Regiment” I replied. His face turned colour. Maybe it was a play of light and shade or maybe it was just my imagination but I thought he was going to be ill. “Are you okay?” I queried? He nodded. “Please carry on”.

After marching through hostile territory, the brigade finally landed at Myebon. Their dis-embarkation was not opposed.They proceeded to Kangaw, little knowing that forty-eight hours later they would be locked in a battle which was to last for a fortnight and claim the lives of three thousand men.

Mountbatten had been right. The withdrawal route of the Japanese was dominated by ‘Hill Feature 170; Melrose. It was firmly held by the Japanese and gave them the enormous advantage of having the ‘commanding heights’. Worse, intelligence reported that they had two brigades. The Indians had one. Brigadier Hutton realised that if the withdrawal had to be cut, the hills would have to be captured irrespective of the numerical disadvantage. He took the call. The first attack by the Hyderabadis under Thimayya mauled the enemy but did not achieve the objective. The second by the Baluchis under Sen met a similar fate. It was then that ‘Reggie’ asked the Punjabis to make a final effort. Artillery and air support was coordinated. The zero hour for the attack was set at 0700 hours on 29 January 1945. At dawn, as the leading companies moved forward, the Japanese opened machine gun fire. The artillery provided cover and laid out a smoke screen. The Punjabis began to climb the hill. Safe from amongst well dug bunkers the Japanese rained fire on them. The Indian casualties mounted as men began to drop. The air cover which was a key part of the plan failed to materialise – bad weather and bad luck. Taking a calculated risk, the commander pushed on. They were hardly a hundred yards from the top when the Japanese threw everything they had at them. In the face of such unrestrained fierceness, the advance faltered hovering uncertainly on the edge of stopping. For the commander, it was the moment of truth — to fight or flee? As he saw his men being mowed down by machine gun fire a rage erupted within him. Throwing caution to the winds he ran forward to be with them. The scales ‘tipped’. The troops rallied, ‘fixed bayonets’ and charged into the Japanese with obscenities and primeval war cries. A fierce hand to hand combat ensued. Neither side took or gave a quarter. The Japanese fought like tigers at bay. The conflict went on unabated through the night. The Japanese counter-attacked in wave after wave but the Indian line held firm. Then the last bullet was fired and there was silence.

Many years later Mountbatten would describe what took place as “The bloodiest battle of the Arakan” and correctly so. The price of victory was two thousand Japanese and eight hundred Indians dead in the course of a single encounter. Fifty officers and men would win awards for gallantry. The battalion commander would be decorated with the DSO for ‘unflinching devotion to duty and personal bravery’. But all that was to happen in the future.

At that particular moment, on the field of battle, the commander was looking at the Japanese soldiers who had been taken prisoners of war. They had assembled as soldiers do, neatly and in order. On seeing the Indian Colonel, their commander called his men to attention, stepped forward, saluted, unbuckled his sword, held it in both hands and bowed. The Indian was surprised to see that his face was streaked with tears. He understood the pain of defeat but why the tears? After all, this was war. One or the other side had to lose. How could the Japanese explain to the Indian that the tears were not of grief but of shame? How could he make him understand what it meant to be a Samurai? Given a choice he himself would have preferred the nobler course of Hara Keri than surrender. But fate had willed otherwise. The ancestral sword in his hands had been carried with pride by his forefathers. Now he was shaming them by handing it over. All this was unknown — unknowable — to the Indian commander. He came from a different culture and had no knowledge of what was going on in the mind of his adversary. Yet there was something in the manner and bearing of the officer in front of him which touched him deeply. He found himself moved. Without being told he somehow intuited that the moment on hand was not merely solemn but personal and deeply sacred. He accepted the sword and then inexplicably, impelled by an emotion which perhaps only a soldier can feel for a worthy opponent, bent forward and said clearly and loudly in the hearing of all “Colonel I accept the surrender but I receive your sword not as a token of defeat but as a gift from one soldier to another”. The Japanese least expecting this response looked up startled. The light bouncing from the tears on his cheeks, reflected an unspoken gratitude for the Indian’s remark. Coming as it did from the heart, it had touched his men and redeemed their—and his—honour. The Punjabis— Hindus and Muslims—who had gathered around also nodded in appreciation. Battle was battle. When it was on, they had fought each other with all their strength. And now that it was over there was no personal or national animosity. Maybe, the Gods who look after soldiers are different from those who look after other mortals for they bind them in strange webs of understanding and common codes of honour no matter which flags they fly.

The moment passed. He looked at the Signal Officer and nodded. The success signal was fired. Far away in the jungles below, Brigadier Reggie Hutton looked at the three red lights in the sky and smiled. His faith in his commanders had been vindicated. He would later explain that at stake that night was not only the battle objective but the larger issue as to whether Indians ‘had it in them’ to lead men in war. There had been sceptics who felt that his faith was misplaced. He looked at Melrose and smiled. Its capture had vindicated his faith. I looked out of the window lost in my thoughts. Suddenly I heard a sob to find that my Japanese friend had broken down. He swayed from side to side. His eyes were closed and it was clear that he was in the grip of an emotion more powerful than himself. He kept saying ‘karma, karma’ and talking to himself in his own language. After a while he looked up with eyes full of tears and holding both my hands said in a voice choked with emotion, “It was my father who gave battle to yours on Melrose. It was he who surrendered. Had your father not understood the depth of his feelings, he would have come back and died of shame. But in accepting our ancestral sword in the manner that he did, he restored honour to our family and my father to me. That makes us brothers — you and I.

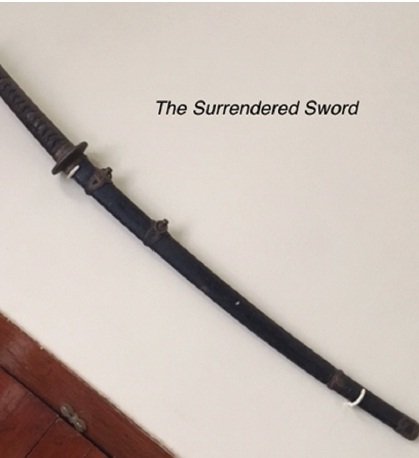

The train pulled into Geneva station. We got down. What had to be said had already been spoken. He bowed. Goodbye I said. Keep in touch. Incidentally, would you like me to restore the sword back to your family. He smiled, looked at me and said “Certainly not. The sword already rests in the house of a Samurai”.

That was the last I saw of him. Usha tells me that the probability of our meeting defies statistics. She should know. She studied economics and statistics. There was a World war going on. Good. My father was in the Indian army; his father was in the Japanese army; perfectly okay. They fought in the same theatre of war—Burma; understandable. They fought in the same battle; difficult but believable. The war finished, they went back to their families; plausible. But that their sons grew up in two different lands, happened to go to Berne at the same time, board the same train, get into the same compartment, share coffee and cigarettes, have a conversation on something that had happened four decades ago, discover their fathers had fought on opposite sides in the same battle — that undoubtedly is insane.

Personally, I do not believe that there are outcomes in life which are necessarily bound to happen?Yet, sometimes I am not so sure. You can never connect events by looking into the future; you can only connect them by looking at the past. Maybe, it is comforting to believe that because the dots connect backward, they will connect forward also. I don’t know. Perhaps in the end, you have to trust in something. The sword has a pride of place in our home. Whenever I see it, my mind goes back to the jungles of Arakan where in the midst of the madness of war, two soldiers were able to touch each other and their compatriots with lasting humanity.

Dr YSP Thorat was Fellow, Lincoln College, Oxford; Executive Director, RBI; Chairman NABARD; Chairman, Agriculture Mission, Government of Maharashtra. Presently, Director, Tata Chemicals, Britannia etc. He is son of Late General SPP Thorat.