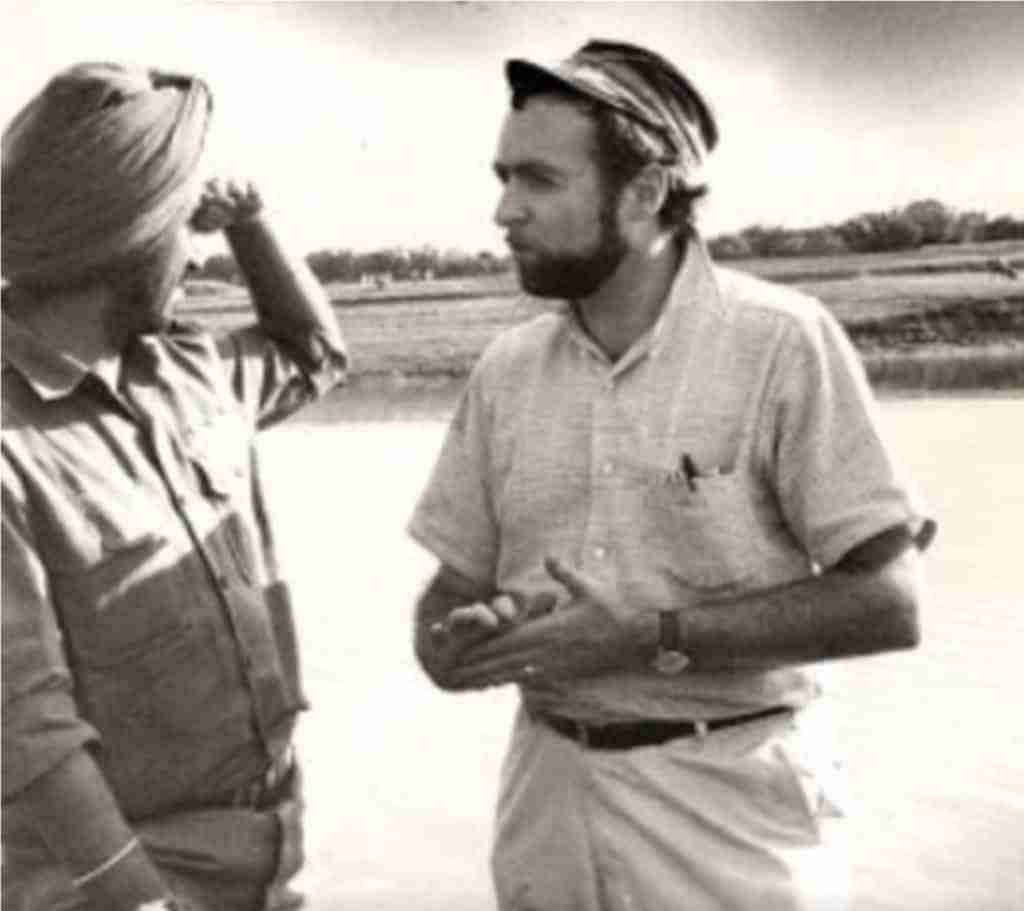

On 13 December 1971, when my battalion 4 GUARDS was at Demra, a suburb of Dacca, we were joined by a group of foreign journalists.

The Schanberg enigma

One amongst them was Sydney Schanberg, a Pulitzer Prize winner and author of “The Killing Fields” an account of the genocide unleashed by Pol Pot on his fellow Cambodians. Schanberg later became the editor of the New York Times. I quote directly from Sydney Schanberg’s account which appeared in the New York Times on 17 December and later:

Sydney Schanberg: “Seven Western journalists were the only foreigners to ride into Dacca with the leading Indian troops—4Guards(Infantry), 5 Independent Squadron(Tanks) and 65 Mountain Regiment (Artillery). The population turned out in droves to sit and watch the Indians rain down shells on the Pakistanis. ‘Good shooting,’ an officer from the command post yelled across after getting a report from the forward observer that they had got some enemy vehicles—the gun crew applauded…Two Indian light tanks captured from the Pakistanis appeared and moved into a position opposite Demra, one in a mango grove and the other 200yards to the left on an embankment. As the tanks were getting into position, Indian artillery shells whistled overhead on the way to the enemy positions. Columns of smoke rose from the buildings there. Then the tanks opened up, pummelling the eardrums and much more devastatingly, pummelling the enemy in the Adamjee Mills complex. Smoke columns began to mushroom from the factory buildings too”.

“After about twenty minutes of pummelling the area with shells, the two tanks opened up with machine guns, peppering the area in front of the buildings. A column of infantry (C Coy 4Guards commanded by Maj Tuffy Marwah and D Coy commanded by Capt Surinder Singh) began making its way forward and then turned right across a marsh towards the river. At about 12.30 pm the Commanding Officer of 4Guards Col Himmeth Singh decided to take the journalists forward to watch the infantry in action. “

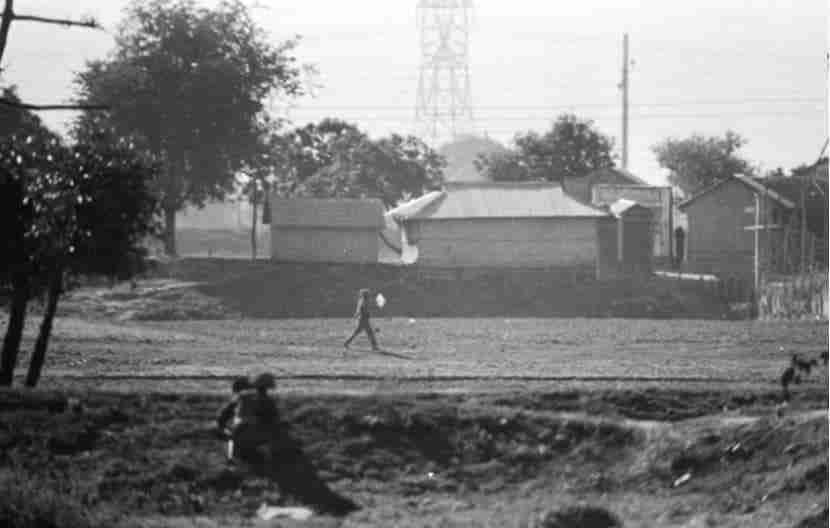

He went on to write, “We walked for about a minute when a Pakistani machine gun began spitting and bullets whizzed by. We flew unsmartly down the opposite embankment, sending up gravel and dust in the wake of our slide. The Pakistanis kept firing and hit a moat which crumbled. For an hour or so, the Pakistanis kept the Indians pinned down. Then the Indian Artillery Officer Major Dhillon appeared and taking position behind a wall yelled at the Pakistanis ‘I want you to put down your weapons and get a move on. I give you one minute. Get your men around you and move to that little boat. Don’t compel me to blast you with artillery. Get moving.’ Then at 1.45 pm, a Pakistani officer came into view on the opposite bank, waving what looked like a big white handkerchief, the scene ending what may have been the last battle of the war”.

by Schanberg.

He further wrote:“I don’t like sitting around praising armies. I don’t like armies because armies mean wars. But this (Indian) army was something. They were great all the way. There never was a black mark…I lived with the officers and I walked, rode with the jawans-and they were all great. Sure some of them were scared at first-they wouldn’t be human if they weren’t. But I never saw a man flinch because he was scared. There was a tremendous spirit in the Indian Army and it did one good to experience it. I have seen our boys in Vietnam—and this army was different. Their arms and equipment aren’t as good-but what they had were used with effect and boy! could they improvise. I saw heavy recoilless guns carried on shoulders, big guns pushed across marshes like ox-carts, by jawans, villagers, officers, everybody was in it together and they were perfect gentlemen. I never saw them do a thing wrong not even when they saw just how bestial the enemy had been.”

Pakistan’s moves

The final ignominy for the Pakistanis was to see the foreign journalists mounted on tanks which had once been theirs, enter Dacca with the leading elements of the Indian troops and be hailed by the jubilant crowds as liberators. Schanberg concludes:

“The road was filled with jubilant Bengalis and troops heading for Dacca on tanks, truck, scooter, bicycle, rickshaw and foot and hitching rides to get to the liberated capital—it was more a circus parade than a military convoy. All along the route, fathers held up their infants up on the air and waved the infants hands at the Indian soldiers.”

Sydney Schanberg: But this (Indian) army was something. They were great all the way. There never was a black mark…I lived with the officers and I walked, rode with the jawans-and they were all great.

Once in Dacca, these captured Pakistani tanks, now manned by our men, were placed in front of the Dacca Intercontinental Hotel, which had been declared as the United Nations and Red Cross Safe Zone. The Hotel provided security to the many foreign diplomats and former civilian members of the East Pakistan Government including its Governor, who had taken shelter inside the hotel. Col Himmeth Singh and Major Shamsher Mehta, seeing an opportunity entered the hotel and after a cup of tea decided to avail of the services of the hotel.

They were ushered into a luxurious suite that was permanently reserved for Zulfikar Ali Bhutto. After two weeks of fighting in the mud and grime, a hot water shower and shave was a greater luxury than a bottle of champagne. Having bathed and shaved and after splashing themselves generously with the expensive colognes that were kept for Bhutto, both departed for their units. Shamsher, however, felt that Bhutto, who was as bald as the bottoms of Anita Ekberg, was in no need of a comb, least of all a set of them.