If any one single operation were to be cited as the turning point of the Bangladesh Liberation War, the heliborne crossing in which the 110 and 105 Helicopter Units of the IAF transported 4 Guards over the Meghna River on 9 December 1971 would take that honour. Those magnificent pilots, airmen and their flying machines performed wonders far in excess of what could legitimately be expected of them. Throughout this and other operations, they displayed the highest levels of professionalism, airmanship and gallantry. But for them, we could not have achieved what we did and Dhaka would have remained a distant dream. However, here, I will tell the story as the company commander of A Company of 4 Guards.

We had harboured for the night at a village named Arhand on the Comilla-Brahmanbaria Highway effectively cutting off Pakistan’s 14 Infantry Division at Brahmanbaria from their other forces at Comilla. In the last seven days of almost continuous battle we had punched a wide hole in the outer crust of defences along the border, captured Akhaura and penetrated about forty kilometres deep and cleared an area forty kilometres wide, creating a suitable launching pad for further operations. Early morning on 8 December, our Brigade Commander, Brigadier RN Mishra came over to the unit and asked my Commanding Officer Lieutenant Colonel Himmeth Singh to accompany him to reconnoitre a possible crossing place on the Meghna River. Major Tuffy Marwah, with Charlie Company had been sent on a search and destroy mission a day earlier and reported on radio that barring light resistance, the area was clear of enemy troops. The Commander left with the CO and I was left in charge of the battalion. With me was Major Shamsher Mehta and his 5 Independent Armoured Squadron. At about 0700 hours, I got a call on my radio set that GOC 57 Mountain Division, Major General Ben Gonsalves wanted to speak to me. The General told me that he could not get through to either Brigadier Mishra or my CO and ordered me to move my battalion post haste to Brahmanbaria. I told the GOC that both the commander and my CO had gone for reconnaissance and were outside my radio range too, and that I would move as soon as I contacted them. The GOC sensed my hesitancy to move the battalion in the absence of orders from my CO.

“Paunchy”, he said, referring to my code sign, “this is Ben” (his code sign). Get your battalion to Brahmanbaria immediately and I will meet you on the Bridge on the Pagla River. I will ask the GSO1 who has a more powerful radio set at Divisional Headquarters to inform Himmeth.”

The GOCs orders left no room for doubt. I assembled the battalion and left a small party behind to apprise my CO and Commander of the latest situation. We then took off for Brahmanbaria mounted on Shamsher’s tanks and some captured vehicles. Shamsher now had 17 tanks, three more than his authorised holding. These PT 76 tanks had been captured at Akhaura. Shamsher’s men, after repairing them, got them on road and they were now a part of his Squadron. These same tanks had played hell into my Company a few days earlier when they, supported by two companies of infantry one each from 12 Frontier Force and 31 Azad Kashmir Regiment had over run one of my platoons and captured seven of my men. Now these tanks were a welcome addition to our force.

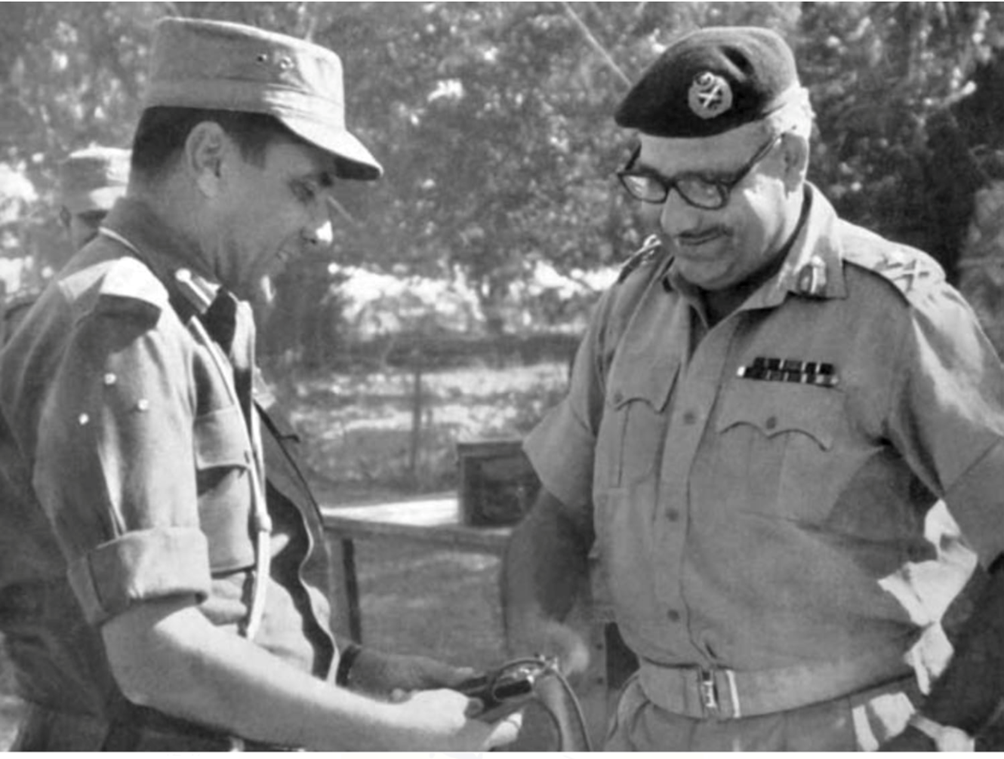

Brahmanbaria was about 15 km from Arhand but the PT- 76 is a fast moving tank and we got there in less than an hour. General Gonsalves was waiting for us at the Bridge, two spans of which the retreating Pakistanis had blown up. With the General was his ADC, helicopter pilot, Major Goraya, the Brigade Major of the Artillery Brigade and some other officers and men. It says something about the quality of our commanders that the first man in Brahmanbaria was the GOC himself. I was brought up on the stories of Rommel and Patton and it was inspiring to see the same qualities being displayed by Indian Commanders.

The General was none too pleased with the Commander, 73 Mountain Brigade, Brigadier ML Tuli for not having closed in with the Pakistanis during the last twenty-four hours. Consequently, Brigadier Tuli was unaware that Brahmanbaria had been evacuated twenty-four hours earlier. It was only when the GOC flew over the town in his helicopter that he realised that the Pakistanis had abandoned the town. Brahmanbaria was an important objective, considering the fact that here was located the headquarters of Pakistan Army’s 14 Infantry Division and 27 Infantry Brigade.

The GOC ordered me to take the battalion into Brahmanbaria and clear the town, but that was easier said than done. The town was across the Titas River, the bridge was down, the river was not fordable and the tanks though amphibious could not carry the extra load of infantry whilst swimming across. We found some country boats, but they had no oars. Some of my men then swam across the river, and using bed lining and ropes, we managed to organise a ferry service, pulling the boats to and fro across the river. In about an hour, 14 Guards was on the far bank. Shamsher had some problem getting the captured Pakistani tanks across as these tanks leaked because of faulty watertight seals. I am not sure how he got them across as by then, I had taken off with my men. In the meantime, Brigadier Mishra and my CO had joined us and so had Tuffy Marwah and his company. They crossed the river a few kilometres downstream and also fought a few actions on the way to our rendezvous that morning.

We now fanned out and commenced securing Brahmanbaria. During our search of their Division Headquarter, we found the bodies of six jawans of 10 Bihar. They had been shot in the back of their heads with their hands tied behind their backs. We also saw the bodies of forty-four local Bengalis, probably Mukti Bahini, lying in a ditch near the stadium. They too had been shot in the head with their hands tied behind their backs. The bodies were lying in the open and dogs and vultures had got to them. It was not a pretty sight, but that too is the reality of war. I pointed this out to General Gonsalves and he was furious.

“When we capture Majid” (Major General Abdul Majid, GOC 14 Infantry Division), said General Gonsalves, “I will have him tried by a court martial and sentenced to death for war crimes and violation of the Geneva Convention on treatment of prisoners”.

Alas, that was not to be as our political masters decided otherwise. We also recovered several top-secret documents, which indicated the haste in which the Pakistani Headquarter staff had abandoned their positions. These we handed over to the Division. I now expected 73 Brigade to take over the advance from us. After the first day of the war, they had been involved in a supporting role and had seen little action, whereas my formation, 311 Mountain Brigade had been involved in continuous fighting and needed time to rest and replenish our ammunition and food supplies.

General Gonsalves however, was not too pleased with Commander 73 Mountain Brigade and so Brigadier Mishra was ordered to resume the advance to Ashuganj, about 20 km away. Ashuganj is a large town on the east bank of the Meghna, and is a twin to a still larger town, Bhairab Bazaar on the west bank. The Coronation Bridge, which was more than a kilometre long, linked the two and was the only bridge on the Meghna.

At about midday we resumed our advance, once more mounted on tanks. D Company under Major Kharbanda moved astride the road and I moved with my company (A Company) on the right flank, both mounted on Shamsher’s tanks. The rest of the battalion was in some civilian transport and captured Pakistan army vehicles. Our most prized and visible position was a red fire engine from the Brahmanbaria fire station. This was requisitioned by Major Tuffy Marwah of C Company who, donning a fireman’s shiny helmet, vigorously rang the bell and sounded the hooter to scare the Pakistanis, but more plausibly, just for fun.

We were subjected to sporadic shelling during the advance but the resistance was minimal until we hit the enemy’s screen position just short of village Talashahar. A shell from an anti-tank gun landed close to the tank on which I was mounted, but fortunately did not explode. We jumped of the tank and then Shamsher assaulted the position with a troop of tanks and overran the enemy there. Kharbanda was not so lucky. In trying to clear the enemy, he charged their machine gun position and received a burst in the upper leg; a few men also died in the heavy firing. Nevertheless, Second Lieutenant Rajendra Mohan and his troop of tanks, retrieved the situation by charging the enemy and clearing the position, otherwise Kharbanda and some of his men would perhaps have been killed.

We advanced another kilometre or so and as the light was fading, took up defensive positions. Getting into a street fight at Ashuganj was not a feasible option at night and we waited for the morrow. The enemy had 27 Infantry Brigade with the Headquarter of 14 Infantry Division and some other troops, totalling some 6000 soldiers here. More importantly, they had an artillery OP sited on top of a 300-foot grain storage silo on the riverbank inside Ashuganj, from where he could observe and bring down effective fire for miles around. We dug our foxholes and settled in for the night. I went to the battalion headquarter which was located in a masjid, on the logic that the enemy would not shell it. That logic proved sound.

At the Battalion Headquarter, The CO’s batman miraculously produced some whiskey. Colonel Himmeth Singh then told me that he had to meet Brigadier Mishra at six next morning at Brahmanbaria and I was to take charge of the battalion in his absence. After a welcome hot dinner, after subsisting for long on cold and wet shakarparas, I returned to my company. My Senior JCO, Subedar Makhan Lal, a veteran of the Second World War and the Kashmir War met me and appeared a bit agitated. He was always cool and calm and I wondered what could have upset him. His cause of annoyance was that four jawans from the Engineers, who were attached to my company had dug their foxholes next to mine, thinking that to be the safest place to be. He had just told them to dig their trenches at an alternate place, but they were none too pleased about starting all over. Just then, the enemy shelling on my position started and we all took cover. When it ceased, Subedar Makhan Lal went round the company position to check up if all was well with the men. He however could not trace out the Engineer boys. I told him to look for them next morning. Early next morning I left for the battalion headquarter where the Adjutant, Captain Vijay Dewan popularly known as Glucose met me and informed me that the CO had left a few minutes earlier in a jeep.

As soon as there was sufficient light, I took a round of the battalion. The forward companies were occasionally fired upon by small arms but as it was doing no damage, we held our own fire not wanting to waste ammunition. When I went to my own company, Subedar Makhan Lal informed me that the missing Engineer boys had been found. When the shelling started, they had taken shelter in the foxholes they had dug near my trench. A shell landed there and they were blasted to smithereens, pieces of their bodies were strung up on the branches of trees around the trench. Indeed, in war, no place can be considered safe.

At about nine in the morning, I received a radio call from the CO, directing me to bring the battalion back post haste to Brahmanbaria and he would give further orders there. He told me that 18 Rajput and 10 Bihar from our Brigade and 73 Brigade were in the vicinity and they would in due course take over the area vacated by us.

I disengaged the battalion and we marched back to Brahmanbaria. I however had to shed Shamsher’s tanks, as they were to join 18 Rajput.

This constant marching to and fro much like the famous ditty about the Duke of York marching his men up the hill and then down again was getting to be a bit irritating, but as every infantryman knows, that is invariably the fate of the Poor Bloody Infantry. By about 0130 that afternoon we reached Brahmanbaria stadium which was our designated RV. The CO met us here and told us that we had been tasked to cross the Meghna and helicopters would be landing soon to take us across.

My reaction was immediate.

“Thank God sir”, I said, “Sagat has chosen to give us helicopters to cross the Meghna. He believes the battalion can do anything; he could very well have told us to swim across the river”.

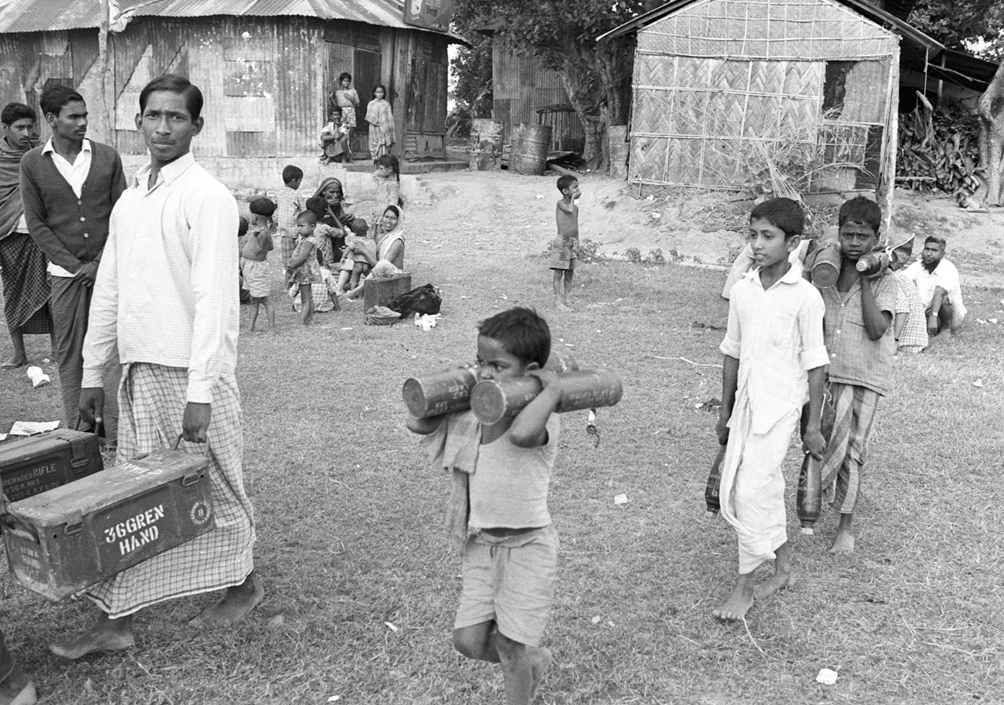

Regardless of the faith Sagat had in our capabilities, the miles wide Meghna was not within our swimming capability. We received new maps, which covered the area from Brahmanbaria to Dhaka and our next objective across the Meghna was the landing zone at Raipura. The preparations started immediately. We worked out the load tables, each helicopter carrying about fifteen soldiers and three or four Bengali porters who were carrying our extra ammunition. The men were warned about the tail rotor of the helicopter, a hit from which would be fatal. Fortunately, most of us had some experience of the Mi 4 Helicopters and this stood us in good stead. Whilst we were tying up loose ends, the helicopters started landing. At the same time, an unending stream of bodies and wounded jawans of 18 Rajput started arriving at the stadium. The battalion had met with a setback at Ashuganj after we had withdrawn.

In the next few minutes, fourteen helicopters were lined up in the stadium. All were without the rear doors of the holds to facilitate easy boarding and disembarking. Precisely at four in the morning, the first four helicopters took off to cross the Meghna. My CO, Colonel Himmeth Singh and I were in the first helicopter, piloted by Squadron Leader CS Sandhu, the Squadron Commander of 110 HU. Seated at the far corner of the hold was Group Captain Chandan Singh, the senior Air Force officer in IV Corps theatre. Both Colonel Himmeth Singh and Group Captain Chandan Singh had already reconnoitred our landing zone earlier in the morning along with General Sagat Singh and Brigadier Mishra. Their helicopters had been shot at on the way home and General Sagat Singh received a bullet that passed through his beret grazing his forehead. A lesser man than him would have been perturbed but Sagat being Sagat, it made no difference to him.

As soon as we were airborne two Gnat fighters flying Combat Air Patrol (CAP), provided us protection. We had the Gnats above and the wide Meghna below and with the noise of the rotors, the scene was akin to a scene straight out of a Hollywood movie, but we did not have even a box camera to record the event. In about fifteen minutes we over Raipura and landed on our designated landing zone (LZ), each helicopter only a few meters from the other. Such was the skill of the pilots that even in the dark, with no or very primitive landing aids, not one mishap occurred. As soon as we landed, the troops took up positions to secure the area and Flying Officer DS Shaheed started to mark the LZ with wet wheat flour dough.

Before the second sortie landed, my CO tasked me to take a reconnaissance patrol to Methikhanda Railway Station, which was reported to be defended by a platoon of para military. I moved stealthily with my small party consisting of my radio operator, Ved Prakash and two men as protection. When we had gone about a kilometre, as if from out of nowhere, thousands of local Bengalis emerged, shouting ‘Joi Bangla-Joi Indira’. In our earlier actions, the villagers would simply disappear but now sensing that the tide was firmly in our favour and the Pakistanis were on the run the locals had taken heart and were emboldened to come out openly in our support.

The Bengalis are normally a noisy people but when excited a Bengali crowd can perhaps be heard several miles away. All pretence at stealth was thrown away and the crowd carried the four of us on their shoulders to the railway station. The Pakistani soldiers at Narsingdi, a large town about 30 km distant had fled earlier on hearing the sound of the helicopters, so we captured the objective without firing a shot. I informed my CO and he told me that he would soon send the rest of my company to link up with me along with D Company.

Young Surinder Singh was now in command of D Company as his company commander had been wounded a few days back. There is a saying in the army that nothing is more dangerous than a subaltern with a map and sure enough Surinder, leading both his company and mine, got lost. It should have taken him at most about forty-five minutes to reach me, but even after five hours, there was no sign of him. This caused me considerable anxiety because in the meantime we had got into a faceoff with some local Mukti Bahini boys who could speak Urdu as they were deserters from the Pakistan Army. The situation could have got out of hand and it took quite an effort to establish our identity. Surinder finally turned up in the morning. It transpired that instead of depending on his compass and map he had relied on a local guide who took the troops to Bhairab Bazar instead of Methikhanda.

Here, they contacted the enemy defences held by troops of Pakistan’s 14 Infantry Division that had withdrawn to Bhairab Bazaar after blowing up the bridge on the Meghna. The enemy reacted violently with heavy shelling and some of our men suffered injuries, but the episode had a positive outcome. The Pakistani’s thought that we had put up a large force across the Meghna to attack them. They went into a shell from which they emerged only on 17 December to surrender to General Gonsalves. In the meantime, C Company under Tuffy provided cover for 19 Punjab to cross over by ferry and it is 19 Punjab that contained 6000 troops of 14 Division until they surrendered.

With Pakistan Army’s 14 Infantry Division holed up at Bhairab Bazaar, the way to Dhaka was clear. On 11 December, 18 Rajput and 10 Bihar were helilifted to Narsingdi, which we had cleared earlier in the day. I played no further role in the battle as in the process of clearing the town, I picked up a bullet in the leg. The show by now however, bar the shouting, was over. On the 12th evening we were in Demra three miles from Dhaka and our patrols accompanied by artillery OP’s had crossed the River Satyalakha. On the 13th, as we started shelling Dhaka Cantonment, General Niazi and the Governor of East Pakistan approached the United Nations and their own Government in Islamabad, asking for an immediate ceasefire.

This was without doubt Sagat’s show; we were the tools that he used and Group Captain Chandan Singh and the helicopter pilots also deserve full credit for making the impossible possible. Without them we could not have done it. Few know that before the war, 4 Corps had been authorised to use these helicopters for a special mission to lift only one infantry company group of about 150 men. It was on the initiative of General Sagat Singh that in the course of the war, they had air lifted more than 6000 troops and 100 tons of stores – a truly unimaginable feat. Why these two helicopter units have till date not been given due credit for their actions and not been awarded the Presidential Colour remains a mystery. Few units are more deserving than these two.