This article is written to highlight the importance of fighting battles on realistic timelines and not on the whims and fancies of political and military leaders. There is no need for symbolism, which can turn out to be very detrimental to the organisation and achieve results which can have long-term negative consequences. While such examples can be taken from militaries all over the world, here, I have taken an example of the hasty US withdrawal from Afghanistan and Juxtaposed it with events that took place in 1965, on the wind-swept fields of Khem Karan.

On the morning of 15 August 2021, the Taliban forces were at the gates of Kabul. During the course of the day, the President of Afghanistan fled the country, Kabul fell without a bullet being fired, and the Taliban were back in control—a déjà vu moment of twenty years earlier.

US President Joe Biden, had earlier declared that all US and NATO forces in Afghanistan would be withdrawn before 11 September 2021 — the date marking the completion of twenty years of the attack on the United States by the al Qaeda. It was a date chosen for symbolism and not for any sound military reason. And this inevitably led to chaotic scenes in Afghanistan, witnessed over the next 15 days, with hundreds of thousands of local Afghans, desperately trying to flee the brutal Taliban regime.

It was not as if the US had lost the war—they had simply lost interest, as newer challenges were emerging in the Indo-Pacific region, necessitating a change in strategy. President Obama had announced a withdrawal from Afghanistan in his first term as President, which he repeated in his second term. Thereafter, President Trump, too, made a strong pitch for withdrawal, which led to the Doha Agreement of 29 February 2020, between the US and the Taliban. The withdrawal of US and NATO forces was thus a foregone conclusion and did not occasion much surprise. But the manner in which the US forces withdrew cast a dark shadow on the entire process and severely dented the image of the US. Had the withdrawal not been linked to a date, the situation, in all probability, would have been different.

Much the same thing happened, with disastrous consequences, in the battle of Khem Karan, fought on 12 September 1965. On this day, troops of 4 Sikh, tasked to establish a road block behind the enemy lines in Khem Karan were routed by the enemy and five officers, including the CO, four JCOs and 125 men were taken prisoner. The battalion was tasked to execute a mission to coincide with Saragarhi Day. This was a monumental blunder, as the task was not predicated on a realistic assessment of the ground situation, but on the desire to capture the objective on a day which held great significance.

The Battle of Saragarhi

On 12 September 1897, a small band of 21 soldiers from the 36 Sikh Regiment, fought to the last man and the last round, a marauding band of Orakzai and Afridi tribesmen, estimated to be over 10,000 in number. This was a last stand battle, heroic beyond measure, and rightly commemorated to this day, as Saragarhi Day. Acting as a signal post between Fort Gulistan and Fort Lockhart, the outpost of 21 men at Saragarhi was cut off by thousands of the Afghan tribesmen, but the Sikhs led by Havildar Ishar Singh refused to surrender. They beat back waves after waves of attacks, till the very last man was annihilated in this very unequal battle. All the 21 soldiers involved in the battle were posthumously awarded the Indian Order of Merit, which was the highest gallantry award that an Indian soldier could receive at the time.

This battle, fought before the Tirah Campaign between the British Raj and Afghan tribesmen, is rightly considered as one of the epic last stands in military history, comparable to the last stand put up by the Greeks against the Persians in the Battle of Thermopylae in 480 BCE. Saragarhi thus stands as a symbol of resistance and 12 September is commemorated every year as Saragarhi Day.

Initial Indian offensive in Khem Karan Sector

When the 1965 War broke out on 5 September 1965, 4 Mountain Division, composed of 7 Mountain Brigade and 62 Mountain Brigade, was employed in the Khem Karan sector. The formation had recently been raised for the mountains and was now tasked to occupy the territory between the border and the Ichhogil Canal. Both the brigades were tasked to capture enemy border outposts on the night of 5-6 September, and accordingly, two battalions each from both the brigades were used for the attacks, with the third battalion being used to set up a firm base for the attacking battalions. Defending the area was Pakistan’s 11 Infantry Division. Unknown to the Indians, Pakistan’s 1 Armoured Division was also in the area.

The four positions attacked in the initial phase were assessed to be held by a platoon strength each of the enemy, but that turned out to be a gross under-estimation. The enemy was holding the front in strength, and all the attacks were beaten back with heavy losses to own troops except in one locality, Theh Pannu, which was captured by 4 Grenadiers. Both the brigades of 4 Mountain Division were badly mauled and what remained after the first night of battle was an effective combined strength of just three and one half battalions. The division then took up defensive positions behind the town of Khem Karan. 7 Mountain Brigade was deployed to guard the Khem Karan-Bhikiwind axis, with the Brigade Headquarter located at village Chima. 62 Mountain Brigade was tasked to guard the Khem Karan-Valtoha axis, and they deployed 18 Rajputana Rifles at village Asal Uttar. The divisional defences thus resembled a horse shoe.

The Enemy Counter Offensive

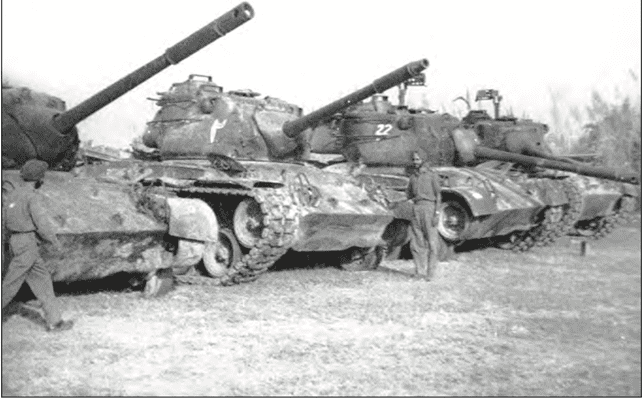

The enemy offensive began at 0800 hours on 8 September, with Khem Karan, which was not held, falling easily to the enemy. Pakistan 11 Infantry Division and 1 Armoured Division thereafter used Khem Karan as a base for their offensive. Over the next three days, the Indian defences desperately held on despite repeated armoured assaults by the enemy. The Indian positions were reinforced by armour, which inflicted further blows on the enemy tanks and by the evening of 10 September, the enemy offensive had ground to a halt. A major portion of the enemy armour had been destroyed, the area being described as the graveyard of the Patton tank. Operation Mailed Fist, as the Pakistani offensive was called, thus ended in failure and the remnants of the Pakistani armoured division were moved out to the Sialkot front, to fight a defensive battle against the Indian 1 Armoured Division which had begun its offensive in that sector. It was indeed a great victory won by 4 Mountain Division, despite its disastrous performance on the night of 5/6 September.

The Plan to retake Khem Karan

Now plans were formulated by India to retake the township of Khem Karan. The plan involved the capture of this border town by 2 Mahar, in conjunction with the establishment of a block behind the enemy by 4 Sikh, to prevent them from escaping. 2 Mahar was then to link up with 4 Sikh. Both these battalions were not part of 4 Mountain Division, but were moved from other sectors for this operation. 2 Mahar was moved from Rajasthan and the battalion only arrived by the evening of 11 September. 4 Sikh was despatched from 7 Infantry Division and this battalion too, reached the location on the evening of 11 September. 4 Sikh had just fought and captured Burki, one of the toughest and most hard fought battles of the 1965 war, so pulling them out at this juncture, to take part in an operation in another divisional sector made little sense. More importantly, the reasoning behind the move was amateurish and violative of every principle of combat.

The Battle of Burki

4 Sikh is the proud descendant of the famous 36 Sikh Regiment of Saragarhi fame. In September 1965, this battle-hardened battalion, under the indomitable leadership of Lt Col Anant Singh, captured a Pakistani village called Burki which was heavily defended, thus bringing once again, fame and glory to the battalion, to the Sikh Regiment and to the Indian Army. The unit had arrived in Ferozepur in August 1965 and was preparing to commemorate Saragarhi Day in a befitting manner, when the call to arms was received on 3 September and the battalion mobilised for war.

7 Infantry Division, of which 4 Sikh was a part, had been tasked to advance on axis Bhikhiwind-Barki-Lahore and secure the east bank of Ichhogil Canal from Jallo to Bedian in the South. After clearing the border outposts (BOPs) astride the road axis, the leading troops of 48 Infantry Brigade contacted Hudiara drain by the evening of 6 September. Simultaneously, 4 Sikh entered Pakistani territory after clearing two posts of Satluj Rangers – Theh Sarja Marja and Rakh Hardit Singh. This was achieved in complete stealth.

On 8 September, two companies of 4 Sikh attacked and captured the village of Brahmanand, approximately 3 km west of the Barki-Lahore road, where the Hudiara drain merged with Ichhogil Canal. The battalion suffered four soldiers Killed in Action (KIA) and 19 injured in this operation. Then, in what can only be ascribed as a missed opportunity and one of the vagaries of war, Maj. Manhas, the company commander of ‘A’ Company noticed a canal bank approximately 2 km away. A reconnaissance patrol sent up to the canal found no enemy there and the troops took time out to have a dip in the cool water of the famous Ichhogil canal. The higher HQ, for some strange reason, refused to believe that this section of the canal was not held by the enemy. It would have given 7 Infantry Division an opportunity to secure both banks without a fight and launch a flanking attack on the well fortified Barki village, but the opportunity went abegging!

On 10 September, 65 Infantry brigade launched the offensive for the capture of Burki, supported with a squadron of Central India Horse (CIH). The attack was led by 4 Sikh, which began its offensive soon after darkness fell on 10 September. After heavy fighting, the enemy position was captured by about 2200 hours, but the area was still being shelled heavily by the enemy. Thereafter, 16 Punjab went through Phase 2, and reached the banks of the Ichhogil Canal.

The casualties suffered by 4 Sikh in this battle were heavy as the Pakistanis put up a spirited defence. 23 soldiers were KIA and 93 were wounded, including two officers. And it was on the morning of 11 September, before the battalion could even savour the fruits of victory, that the CO, Lt Col Anant Singh was given orders to collect his battalion and move out for an offensive operation in a neighbouring sector, to capture Khem Karan. The operation was scheduled for that night.

A message received at about 8 AM on 11 September, when the battalion was still reorganising on the objective, stated that the CO, Lt Col Anant Singh was required to report immediately to HQ 7 Infantry Division to meet the GOC, Maj. Gen. H.K. Sibal. There, the General told him that the Army Commander had a special task assigned for him. The CO apprised General Sibal that the battalion needed time to rest and refit, but that cut no ice with the latter. So he then went to meet the Army Commander as ordered.

The Army Commander, Lt Gen. Harbakhsh Singh, was also the Colonel of the Sikh Regiment. He was well aware of the regimental history – more so of the world-famous battle of Saragarhi. General Harbakhsh wanted 4 Sikh to capture another objective in the area of operations of a different division, to commemorate that great event. How could Anant refuse? The objective given was in the neighbouring Khem Karan sector. ‘Further instructions to you will be given by GOC 4 Mountain Division,’ said the Army Commander. ‘I shall personally come to you on 12 September, on your battalion’s Battle Honour Day, when you would have added another chapter to your glorious record.’ On such flimsy reasons was an attack planned with troops who had not seen the area and who had fought a battle of a lifetime just the previous night.

At 11.30 AM, Anant sent a message to his unit to de-induct from Barki. Though tired, the troops walked back to the B echelon area, amid constant shelling by the enemy. Here, they finally got a hot meal, after having engaged in battle for six days on end. The battalion then moved to Valtoha in transport, some 40 km away, and reached there at 10.30 p.m. on 11 September. The CO had reached HQ 4 Mountain Division near Valtoha earlier, by 4 p.m., and an hour later, was briefed by the GOC, Maj. Gen. Gurbaksh Singh.

The Battle of Khem Karan: 4 Sikh Establishes a Road Block

Giving information about the enemy in his sector, the GOC told Anant that the Pakistanis had suffered major reverses in the last three days and were on the run. He stated that Pakistani armour had either been destroyed or had withdrawn and now only a weak company was defending Khem Karan, the small township which the Pakistanis had captured a few days earlier. He had tasked a brigade of his division to clear Khem Karan. The task of 4 Sikh was to establish a road block behind the enemy, astride Khem Karan-Kasur Road, in conjunction with the above attack, to prevent the enemy forces from escaping. Anant was told that the attacking forces would be supported by armour and was assured that the link up with 4 Sikh would be completed by 8 AM on 12 September positively.

4 Sikh was and remains a very distinguished and battle hardened battalion. But the task given was not only impossible but absurd to the extreme. Over the last five days of battle, 4 Sikh had suffered 3 JCOs and 36 soldiers killed in action (KIA) and about 121 wounded. The unit strength was depleted, men needed rest, casualties were to be tended to, and there was acute necessity of replenishment. Despite this, a new task was now being given in a different divisional sector and that too without allowing any time for reconnaissance.

By midnight, the available fighting strength of the battalion, about 200 plus men, had assembled for the task. The CO briefed the men and they moved out at 1 a.m. for the mission. The task involved an approach march of 18 km to the road block site, which was to be effective by 5.15 AM on 12 September. Despite all the challenges faced, the CO with his men reached the site by 4 AM and set up the block as ordered. From here on, the situation degenerated from bad to worse, resulting in the capture of the CO and a large body of the men who were with him.

It transpired that Khem Karan was well defended and still had tanks as part of its defence. Lt Col Bakshi, CO 2 Mahar, had moved ahead of his battalion from Jodhpur travelling nonstop, and was totally unfamiliar with the area. His battalion had no time to even reconnoitre the area and were pushed into battle to capture an objective, to coincide with Saragarhi Day. But the enemy was in far larger strength than anticipated and the attack failed. In this entire sorry episode, 2 Mahar and 4 Sikh had no time to even discuss battle plans with each other. Both battalions were literally thrown to the wolves. In the event, the road block was surrounded by the Pakistanis and 125 men, 4 JCOs and 5 officers, including the CO, were taken prisoner. The operation was ill-conceived and thoroughly bungled by inept higher commanders, but 4 Sikh had to bear the stigma. In this sorry episode, Brigadier Sidhu, the Commander of the brigade, was made the fall guy and was removed from command.

Epilogue

Like the US withdrawal from Afghanistan in August 2021, which was predicated on a deadline, to be completed by the twentieth year of the war, the hasty attack on Khem Karan was again launched to recapture an objective on Saragarhi Day. The reasoning was flimsy and amateurish, but the consequences were horrendous. An attempt was made to shift the blame for the fiasco on the CO of 2 Mahar, but the Brigade commander intervened and took the responsibility on his broad shoulders. He was removed from command, but he showed great moral courage in protecting his subordinates from being unfairly treated. The same cannot be said for these higher in the chain of command. Fast forwarding the operation and forcing his command down the line to launch an attack on 12 September was the brainchild of the Army Commander, Lt Gen Harbakhsh Singh. He should have owned responsibility for the same, but he maintained a studied silence throughout. With the CO 4 Sikh and a large body of his troops being taken prisoner, the sacrifice of the officers and men of 4 Sikh in capturing Burki was never acknowledged. Sadly, none of the military leadership who ordered this to happen suffered the consequences of their action.