On 14 June 1905, the crew of the Russian battleship Potemkin led the first abortive revolution against the oppressive conditions of the Tsarist rule. That moment of revolt is preserved and perpetuated in Russian culture, history and national consciousness.The world famous epic film by Eisenstein, Battleship Potemkin, (a milestone in cinematography) even today evokes a fervour in the minds of the audience.

On 18 February 1946, Indian sailors of the Royal Indian Navy revolting against the oppression of their British officers, lowered the Union Jack on the ships in Bombay. The revolt spread to the ports at Karachi, Vizag, Madras, Cochin and Calcutta encompassing 10,000 sailors in eighty ships and shore establishments. Sadly, the saga of these heroic sailors are today just a mere footnote in our history and seldom known to many. A monument erected for these brave hearts at Colaba, Mumbai stands mute testimony to their forgotten valour.

The Prelude

The Second World War saw the rapid expansion of the Royal Indian Navy (RIN). In 1945, it was ten times larger than its size in 1939. Recruitment was no longer confined to martial races; men from different social and educational strata were recruited. The Second World War also changed global views and the Indian soldier was no exception to this change. Exposure of the Indian forces in many battle theatres during the World War made them realise that the British were not invincible and their post war experiences in the colonies made them realise that they were helping the British to oppress the peoples in the colonies, while their own country men were fighting against the British oppression in India.

The end of war meant demobilisa-tion and unemployment. The variances of salary, accommodation and perks with the British counterpart and the harsh treatment of Indian soldiers by the British too exacerbated tensions. There were at least nine minor mutinies between March 1942 to April 1945. Labor unrest also rose with the closure of factories producing war like stores. Nationalism was further fuelled by the reminiscences of the Quit India Movement and the INA armed struggle. The INA trials at Delhi was a rallying point of the time.

The Opening Gambit

HMIS Talwar was the signal-training establishment of the RIN at Bombay. With 1500 officers and sailors on board, it was the second largest training centre in the whole Empire. The squalor on board the Talwarand the harsh treatment, poor food and the racism of the British officers was brewing discontent in the sailors. A few sailors formed a clandestine group called ‘Azadi Hindi’ and planned to create general disorder and unrest on Talwar. On Navy Day, 1 December 1945, they painted ‘Quit India’, ‘Inquilab Zindabad’ and ‘Revolt Now’ all over the establishment and chanted these slogans when Commander-in-Chief General Auchinlek came on a visit. BC Dutt, one of the leaders of the RIN Revolt stated in his memoir, ‘The barrack walls were no longer high enough to contain the tide of nationalism’. The Press gave ample coverage to this incidents and although the events were confined, word spread to all the ships and shore establishments in Bombay. Ratings openly began to discuss politics, read nationalist newspapers, set up a INA Relief Fund and submitted individual letters protesting against their plight.

Ripple Effect

On February 17, British officers ignored the ratings demand for decent food On 18 February, 1500 ratings walked out of the mess hall in protest, a clear act of mutiny. Rejecting the appeals of the British officers they stated that ‘this is not a mere food riot. We are about to create history…a heritage of pride for free India.’ The ‘Strike Committee’ decided to take over the RIN and place it under the command of national leaders. A formal list of demands called for release of all Indian political prisoners including INA POWs and naval detainees, withdrawal of Indian troops from Indonesia and Egypt, equal status of pay and allowances and good Indian food. It also formally asked the British to quit India.The next day, ratings from Castle and Fort Barracks in Bombay, joined in the revolt when rumours spread that HMIS Talwar’s ratings had been fired upon.

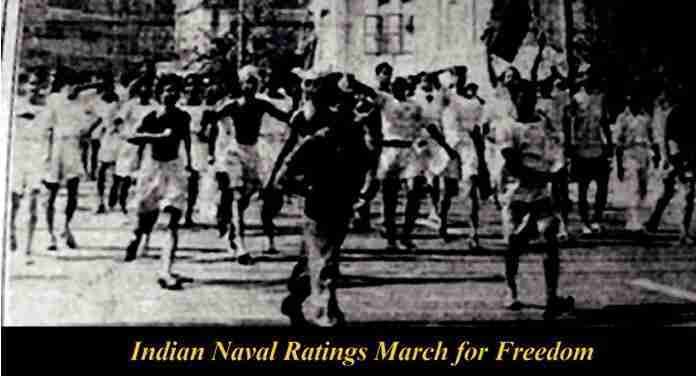

Only the Free Press Journal offered it’s columns to the ratings, as most of the Press were confused at the true nature of events. By nightfall, AIR and BBC broadcasted the news of the RIN revolt spread across the country.The next morning, sixty RIN ships harboured at Bombay – including the flagship HMIS Narbada, HMS Madras, Sind, Mahratta, Teer, Dhanush, Khyber, Clive, Punjab, wana, Berar, Moti, Jamna, Kumaon, Oudh- and eleven shore establishments, including the large Castle Barracks and Fort Barracks, pulled down the Union Jack and hoisted the three flags of the Congress, the Muslim League and the Communist Party. Under the ‘joint banner’ of Charka-Crescent-Hammer and Sickle, the ratings marched in thousands towards the epicenter, the HMIS Talwar. The dawn of February 20, saw the revolt spread to the naval stations at Calcutta, Karachi, Madras, Jamnagar, Visakhapatnam and Cochin. Nearly eighty ships, four flotillas, twenty shore establishments and more than 20,000 ratings joined the revolt. In 48 hours, the British in India had lost it’s Navy. A newly-formed Naval Central Strike Committee (NCSC) included representatives from all the ships and barracks of Bombay. Leading Signalman MS Khan and Petty officer Madan Singh were elected President and Vice President. The RIN renamed as the ‘Indian National Navy’.Decisions were taken to follow a non violent form of struggle and obedience to nationalist leaders. However the nationalist leaders and parties adopted an ambivalent stand and no advice came from them. The British, deducing that nationalist leaders were not keen to support the uprising, Admiral Godfrey, the Flag Officer Commanding the RIN, reached Bombay to negotiate with the NCSC. The political inexperience of the young NCSC made them hesitate, and they accepted Godfrey’s demand that they return to their respective ships and barracks. Within an hour, army columns surrounded the barracks. In response, the ratings discontinued their hunger strike, broke open the magazine and prepared for battle.

India’s Potemkin Hour

The British on discovering that the Maratha soldiers ordered to attack the barracks, were sympathetic to the ratings, were replaced with British troops. Naval Rating Krishnan became the first martyr of the attack that followed. Spirited resistance against the attacks on both Castle Barracks and the ships resulted in a stalemate. That news of British naval ships sailing on to Bombay and the rumours of large casualties forced the NCSC to appeal to the national leaders for help. There was no help forthcoming from them but the people of Bombay rose in support. Thousands of people thronged the Gateway of India with fruits, milk, bread and vegetables. The ratings came by motorboats and collected the supplies. Shops and hotels of all communities in Bombay opened their establishments for free for the ratings. Indian troops did not intervene and turned a blind eye. The Bombay Students Union and the CPI called for a general strike and the NCSC appealed to the people to make it a success. Though the national leaders of the time frowned upon this and called for normalcy the strike shook the city. The strong arm tactics of the British troops caused casualties in the population and several military vehicles were torched in retaliation. The firing by troops around Parel resulted in several civilian casualties. Curfew was imposed in Bombay by dusk. At Karachi Harbour, HMIS Hindustan resisted British small-arms throughout the 21 February. The Gurkha and Baluch regiments had however refused to fire at them. On 22 February, the British positioned artillery around the ship, and once the tide ebbed, opened fire. As the Hindustan’s levels had dropped, it was difficult for the ratings to aim their guns. After an half hour bombardment and six ratings dead, the ship surrendered. HMIS Kathiawad, was racing towards Karachi in response to distress calls from Hindustan. However realising that Hindustan had been taken over, they turned course towards Bombay. HMIS Bahadur still continued resistance. The 2nd Battalion of the Black Watch stormed the Bahadur and proceeded to capture the shore establishments on Manora island. The revolt in Karachi had been put down.

Surrender

Abandoned by the major political parties, the NCSC was disheartened. The British flew a British air squadrons over the ships as a force demonstrator. The RIAF bomber squadron at Jodhpur piloted by Indians had developed a sudden engine trouble. A 25 pounder gun fitted in an old ship fired salvos towards the Castle barracks and British destroyers from Trincomalee had positioned themselves off the Gateway of India. Admiral JH Godfrey went on air with his order to “Submit or Perish”. The NCSC leadership agreed that ‘the debt of this blood has to be repaid a hundred fold’ and made order against any unconditional surrender. Sardar Patel intervened to assuage the NCSC of meeting their legitimate grievances but cautioned against continuance of the revolt. The NCSC were divided on the issue and the majority voted to call for cessation of hostilities. Ironically, Jinnah in his message specifically asked the Muslim ratings to surrender!

On 23 February, at 6am, all ships surrendered. The troops of Thane based HMIS Akbar refused to surrender, but had to capitulate in face of bayonets. When HMIS Kathiawad reached the Bombay coast, it found the royal Cruiser HMS Glasgow blocking its way. In a last act of valiant defiance, the little Corvette threateningly aimed its12 pounder gun at the larger adversary. In deference to the brave show, Glasgow did not impede the ship from sailing into Bombay harbour. The surrendered troops would be housed in inhospitable conditions at Mulund Camp , totally ignored by the Indian political parties and leaders. A total of 476 sailors were discharged from the RIN for participation in the revolt. Seven RIN sailors and one officer were killed and thirty three RIN personnel and British soldiers were injured.

Peoples Revolt

The movement had, by this time, inspired by the patriotic fervour sweeping the country, started taking a political turn. Public mood burst in scenes of the barricades of the French revolution. Stones met bullets at the barricades dotting the streets of Bombay. On 25 February, the official tally recorded 228 civilians and three policemen dead, and 1,046 people and 91 policemen and soldiers injured. The national parties called for calm.

In Calcutta, the Union of Tramway Workers strike paralysed large parts of the country. In Majerhat in Calcutta, jawans and NCOs of the 1386 Indian Pioneer Company joined the strike. When the Commanding Officer slapped a Naik Budhan Sahab, he was slapped back. The last NCSC statement released on the night of 22 February, read, ‘Our strike has been a historic event in the life of our nation. For the first time the blood of men in the Services and in the streets flowed together in a common cause. We in the Services will never forget this. We know also that you, our brothers and sisters, will not forget. Long live our great people. Jai Hind’.

Tributes

Salil Chaudhury penned a revolutionary song in honour of the revolt in 1946 and a commemorative tribute was written by Hemanga Biswas, both veterans of the Indian Peoples Theatre Association and Marxists. Kallol, a play by Uptal Dutt ran to packed theatres in Calcutta till it’s later ban by the state Congress government. Incidentally, Stalin too had banned the film Battleship Potemkin, fearing unrest. The revolt also features prominently in the novel Bhowani Junction by John Masters. The RIN Revolt has since been renamed the Naval Uprising. In addition to the statue which stands in Mumbai opposite the sprawling Taj Wellingdon Mews, two prominent leaders of the Revolt, Madan Singh and BC Dutt, have each had ships named after them by the Indian Navy. The 2014 Malayalam movie Iyobinte Pustakam features the story of a Royal Indian Navy mutineer returning home along with fellow mutineer.

Postscript

Mr P V Chakraborty, (former Chief Justice of Calcutta High Court), Acting Governor of Bengal in 1956, asked Lord Clement Attlee, British Prime Minster, visiting India, at the Raj Bhavan “The Quit India Movement of Gandhi practically died out long before 1947 and there was nothing in the Indian situation at that time, which made it necessary for the British to leave India in a hurry. Why then did they do so?” In reply, Attlee cited several reasons, the most important of which were the INA activities, which fractured the very foundations of the British Empire in India and the RIN Revolt which made the British realise that the Indian armed forces could not be trusted to support the continuance of the British Empire in India. Queried about the extent to which the British decision to quit India was influenced by Mahatma Gandhi’s 1942 movement, Mr. Attlee’s lips winded in smile and disdain and uttered slowly, “Minimal”. The British had consistently feared united mass movements. Non violent movements could be suppressed, but they could not risk facing another ‘Quit India’, this time with trained veterans of the INA and RIN with recourse to armed struggle. A year later, they would depart before the Jewel in the Crown could rise in total revolt.

Colonel Joe Purakel is a veteran of the Regiment of Artillery. An alumnus of OTAA and DSSC he is leading a retired life devoted to writing and gardening.