On the demise of Maharaja Ranjit Singh on June 23, 1839, his eldest son Kharak Singh, an imbecile and opium addict, ascended the throne with the all-powerful Dhian Singh as the prime minister. To understand the sudden collapse of the mighty Khalsa kingdom, it is necessary to familiarise ourselves with the important actors who played the self-destroying game of intrigue in the Lahore Durbar, which ended in the enthronement of Dalip Singh in September 1843 at the age of five, with his youthful mother Jindan as the regent.

The main actors in the tragic drama were, progeny of Ranjit Singh — Kharak Singh and his son Naunihal Singh, Sher Singh, Pishora Singh, Kashmira Singh and Dalip Singh, Dogra brothers of Jammu — Gulab Singh, Suchet Singh, Dhian Singh and his son Hira Singh.

All had been bestowed the title of Raja by Ranjit Singh, with Hira Singh treated at par with his progeny by the Maharaja, the Dogras, especially Dhian Singh, were despised and feared by the Sikhs because of the patronage of the Maharaja and, after the latter’s death, by Dhian Singh’s skillful machinations of power groups in the Durbar and the army.

Ranjit Singh’s co-lateral Sindhanwalias — Attar Singh, Lehna Singh and Ajit Singh who aspired for great power in the Durbar and Lord Auckland and later Lord Hardinge, the Governor Generals who had plans to annex Punjab after the death of Ranjit Singh. During the short period of four years after the demise of Ranjit Singh, only Prince Dalip Singh and Gulab Singh Dogra survived the internecine war. Each aspirant to the throne or prime ministership had to win the support of the army through offers of increase of pay which brought in the phenomenon of the panches to bargain on behalf of the soldiers.

The braves of Punjab

The discipline of the soldiers became lax and soon the panches acted as a repository of power and important decisions could be taken only with their approval. Most of the Sikh Sardars sought safety by leaving Lahore and going to their jagirs. The field was now open for the neo-Sikh upstarts like Lal Singh and Tej Singh who were appointed prime minister and commander-in-chief respectively with the concurrence of the panches. With no roots in the Punjab, Lal Singh and Tej Singh soon realised their safety lay in the early destruction of the Khalsa army. In a treacherous collaboration with the British, they succeeded in inviting defeat of the army during the First Anglo-Sikh War 1845-46.

The British were not slow to annex Punjab in 1849 after the Second Anglo-Sikh War. The British now undertook to debilitate the Sikh leadership, especially those who had fought against them, by the forfeiture of their jagirs and other privileges and banished all persons from the Punjab. The British had demobbed the Sikh army on its surrender and banned possession of weapons. Side by side with the above, they raised two regiments — Ferozepur Sikhs and Ludhiana Sikhs — after the First Anglo- Sikh War. They also raised the Guides Corps from the Doab and Malwa regions in 1847.

To keep the demobbed soldiers from robbery, dacoity and other acts of lawlessness, they raised 10 regiments of Punjabis (five infantry and five cavalry) and the Punjab Irregular Frontier Force (PIFFERS) in 1849. The rest of the demobbed soldiers went digging the Madhopur Canal. The composition of the newly-raised PIFFERS was 25 per cent Sikh, 25 per cent Punjabi Muslim, 25 per cent Dogra and 25 per cent Hindustani. To impress the Punjabis about their military might the British deployed nearly half of 23,000 European soldiers and 36,000 Hindustani troops of the Bengal Army in the Punjab.

To assuage the Sikhs Lord Dalhousie issued orders that Sikhs entering the Bengal Army should receive pahul and should observe strictly the code of Sikh conduct. Henry Lawrence, as the chief commissioner, won the hearts of the Khalsa by restoring the personal jagirs and also those attached to the gurudwaras. The soldiers’ right to their hereditary land was also restored. By 1850, Sikhs and Punjabi Muslims were made eligible to service in the Bengal Army.

Punjab had slowly returned to a peaceful existence after a life of turmoil. The British were now supreme on the Indian subcontinent. Dalhousie was now set on a course to absorb princely states into a direct rule under the company with his new policy of nonrecognition of an adopted son for his eligibility for kingship after the death of a ruler. This had naturally antagonised and scared the ruling princes and big feudal zamindars. By now a belief was growing among the sepoys that the British were trying to convert them to Christianity.

Fighting on

Since 1840, the number of British evangelicals was on the increase among the Company’s administrators who wanted not just to rule and administer India but also redeem and improve it. The annexation of Oudh in 1856 brought about considerable unease in the Bengal Army which was recruited mainly from that region. In this environment, the introduction of the cow/pig fat cartridges was perceived as an attempt at defilement of their religion and acted as a spark in the inflammable atmosphere.

The Mutiny started unexpectedly at Meerut when on May 10, 1857, Hindustani troops attacked Meerut jail and released their fellow comrades who were put in jail for refusing to fire the new greased cartridges. Amazingly, the British troops in the cantonment did nothing to restore law and order. Faced with the gravity of their new situation, the mutineers decided to march to Delhi during the night before the British troops could arrive with their superior new rifles and artillery. The cavaliers reached Delhi early in the morning of May 13.

Faced with the gravity of their new situation, the mutineers decided to march to Delhi during the night before the British troops could arrive with their superior new rifles and artillery.

They placed their services in the hands of the Mughal Emperor Bahadur Shah Zafar, aged 82, whom they regarded as their legitimate ruler. The Mutiny was an odd and spontaneous occurrence where a Muslim Emperor was pushed into rebellion against an alien Christian power by a mutinous army of overwhelming Hindu sepoys from the Oudh region. On the outbreak of the Mutiny Lord Canning invested the judiciary with special powers of summary justice. His directive to General Anson minced no words: “Dispose speedily of Delhi and make a terrible example.

No amount of severity can be too great. I will support you in any degree of it.” Anson ordered the British troops to move to Ambala from Shimla Hills, while Lawrence, appreciating the strategic importance of the Punjab, decided to secure the important forts and arsenals at Lahore, Amritsar, Phillaur and Rawalpindi using British troops and PIFFERS. His next step was to disarm suspect Hindustani units before they got wind of the Mutiny.

Johnson and Anson were clear that the early capture of Delhi would decide the future of India. Anson reached Delhi Ridge along with the troops from Simla Hills and Ambala on May 24, 1857 and decided to attack Delhi on the arrival of reinforcement under raisings in Punjab and the siege artillery train from Phillaur.

The power of numbers

In the meantime, mutineers from Oudh and areas around Delhi had reinforced the Mughal force in Delhi. By the middle of June, the Mutiny had spread to most of north India. By now, the Muslims were nearly half of the force in Delhi. The army under the British consisted largely of Pathans, Punjabi Muslims and Sikhs. Indians formed nearly 4/5th of the force. Out of a total force of nearly 51,000 Punjabi troops, 15,000 were Sikhs. The Sikhs, of course, did not form more than 20 per cent of any regiment. Interestingly, Maharaja Patiala had told the chief commissioner that “the Punjab troops on no account should exceed 1/3rd the whole of native troops”.

The Mutiny, in reality, was a chain of different risings whose form, timing and aim were determined by personal, regional and local grievances and passions.

Similarly the Raja of Jind had told the British, “The Sikh troops had rebelled against and killed their own rulers. How could they care more for the British!” Bombay and Madras Presidencies remained peaceful except for a few local mutinies while Calcutta itself was peaceful. No reigning prince of importance joined the Revolt and they supported the British with money and troops. Maharaja of Patiala, Raja of Jind and other cis-Sutlej princes offered 17,000 troops as did the Scindia for use in Gwalior and Agra areas. Jung Bahadur, the Prime Minister of Nepal, offered 8,000 troops and 20 guns in June 1857 and later these troops were used for elimination of mutineers in Oudh and especially Lucknow.

While the British had better military leadership, weapons and an overall plan, the mutineers lacked cohesion and nationalist spirit. The Mutiny, in reality, was a chain of different risings whose form, timing and aim were determined by personal, regional and local grievances and passions.

By June 1857, the whole of Oudh region, except for a few garrisons like Lucknow, Kanpur and Allahabad, was under the sway of the mutineers and a large proportion of the population, considering it an opportune time to loot, had turned it into a rebellion. Atrocities and barbarities abounded on both sides. By the middle of June, the build-up for the recapture of Delhi was in full swing. Hodson, with his cavalry regiment, was the first to arrive from Punjab.

He soon set up a network of spies under Rajab Ali. It was soon obvious that the mutineers lacked a unified command. Leaders of Nimach Force, subedars of Delhi and Meerut regiments were openly complaining against Bakht Khan of Bareilly Brigade to the Mughal. In late August, in an encounter near Najafgarh, Bakht Khan did not go to the help of Nimach Force which was badly mauled by Nicholson. Finally, the overall responsibility of command reverted to Mirza Mughal, the son of Bahadur Shah. Nicholson, with a mobile column from the Punjab, reached the Ridge on August 14 and got busy with the plans and preparations for the capture of Delhi.

Pressing on

The assault went on in September after a long and heavy bombardment by the siege guns and Delhi was captured on September 20 after a bitter struggle. Before the dawn of September 17, Bahadur Shah slipped out of the Red Fort through the water gate without even informing his prime minister.

He, along with his family and the princes, had moved into the Humayun’s Tomb. Hodson’s informers had kept him well-informed about the location of the Emperor. On September 21, Hodson, along with Risaldar Man Singh and an escort of the Sikhs from Hodson’s Horse brought the Emperor, a prisoner now, to the Red Fort.

Next day, Hodson brought back the three princes from Humayun’s Tomb, and, near the Khooni Darwaza he ordered them to get out of their cart and shoot them dead, having removed their rings and other jewellery from their bodies. The following day, Hodson wrote to his sister, “I am not cruel, but I confess I did enjoy the opportunity of ridding the earth of those wretches.”

Edward Vibart wrote to his uncle Gordon. “The regiment was ordered to clear the houses between the Delhi and Turkman Gates… and the orders were to shoot every soul. I think I must have seen 30 or 40 defenceless people shot down before me… Heaven knows I feel no pity… it must be so for these black wretches shall atone with their blood for our murdered countrymen… and their son… shall never shrink (from bloodshed) for God has given him both strength and courage.”

Nana Sahib, the adopted son of the last Peshwa, lived at Bithoor with a body of a few hundred retainers near Kanpur and had been denied the pension and the title of Maharaja in 1851 on the death of his adopting father. On the outbreak of the Mutiny, he played a double role of a loyalist while conspiring with the mutineers. Wheeler believed that, as a Maratha amongst the alien Oudhies, he was not likely to coalesce with them.

Wheeler also believed that the Kanpur mutineers would march to Delhi, like those at Meerut and, as such, would leave him alone. On July 5, Nana was hailed as the new Peshwa by the mutineers and on June 6, he sent a message to Wheeler that he would attack Kanpur the next morning. Somehow, a determined attack with maximum force was never launched at Kanpur or other places.

The small scale attacks inflicted casualties but brought no decision. By June 13, the garrison was running desperately short on food, medicines and water. On June 25, Nana sent a message to Wheeler written in English under his signature: “All those who are in no way connected with the acts of Lord Dalhousie and are willing to lay down their arms, shall receive a safe passage to Allahabad.”

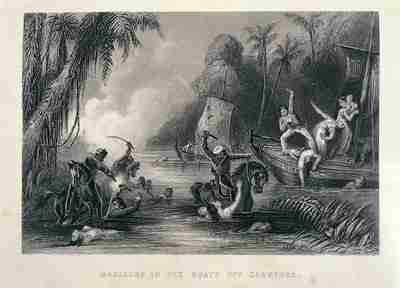

With no hope of reinforcements, dwindling numbers and exhausted troops, Wheeler agreed to an arrangement for the evacuation of Kanpur in boats to be provided by Nana and safe conduct of the garrison to Allahabad. On June 27 morning, the garrison, including families, moved out of the camp and embarked into the boats. On a signal, the hidden men on the bank opened fire on the personnel in the boats.

The thatched roofs of the boats caught fire and most of the passengers including Wheeler were killed, wounded or murdered as the boats floated in the river. Only four survivors made it to Allahabad. The British reaction was swift. Major General Havelock left Allahabad on July 7 with a force of 1,185 men and 6 guns.

After clearing Nana’s troops en route, he captured Kanpur on July 17. He now learnt that about 200 European Christian women and children had been incarcerated by Nana in a nearby compound called Bibighar. On hearing about the approach of Havelock’s force on July 15, Nana had ordered the massacre of the captives fearing that “if they were left alive, they would reveal everything.”

The captives were murdered and thrown into a nearby well. The ghastly murder and alleged rape of women inflamed the victors who now indulged in excessive and unforgiving orgy of vengeful brutality against Indians without remorse. The next objective of the British was the urgent relief of Lucknow as they feared a repeat of Kanpur.

On September 19, Havelock’s troops crossed the Ganges at Kanpur to relieve Lucknow. In the pouring rain, Havelock’s troops captured Alam Bagh about 5 miles from Lucknow by the evening of September 22. The final assault to establish a link with the Residency was launched on September 25 and in two days of fighting, the relieving troops suffered 535 casualties including two brigade commanders dead.

Team work

In view of unyielding resistance, he decided to reinforce the garrison at Lucknow as he was in no position to clear Lucknow of the mutineers or fall back to Kanpur with the sick, wounded and the families. In the next attempt Campbell moved from Kanpur for the relief of Lucknow with a force of 4,700 men and 49 guns. He had secured Alam Bagh. The strength of the mutineers, by now, had increased to nearly 100,000 with the arrival of Bakht Khan’s force ex-Delhi and locals.

Realising the strength of the mutineers and their build-up for defence, he decided to avoid a direct attack. Moving his force along the Gomti River he advanced quickly and established a tenuous contact with the Residency. In a brief discussion with Havelock and Outram, Campbell decided that he would fall back to Kanpur with the sick, wounded leaving Outram with 4,000 troops to garrison Alam Bagh. Meanwhile, Havelock died of dysentery leaving Outram to commander a rebelheld Lucknow. On the return journey to Kanpur Campbell learnt that Nana’s troops were threatening Kanpur.

His first priority was to send the women and children to Allahabad by river boats. Then, he moved his force stealthily into position on December 6 and attacked Nana’s troops who fled in all directions when attacked suddenly. Fred Roberts, later Field Marshal and hero of Kandahar, wrote: “… wounded men were lying in all directions, and many mutineers were surprised calmly looking… The sepoys scattered over the country, throwing away their arms and divesting themselves of their uniforms that they might pass for harmless peasants”.

Nana narrowly escaped capture at Bithoor. In January 1858, Canning moved to Allahabad to be nearer to the scene of action. The plan was launched for a three-pronged attack on Lucknow and to ensure that no mutineers escape so as to end rebel activity once and for all in the Oudh region.

The attacks had begun and by then the only prominent rebellion leader left on the scene was Lakshmi Bai, the Rani of Jhansi, who too, in her unrelenting fight with British died thereby establishing herself as a legend. The major leaders of the Mutiny had been removed from their strongholds by the middle of 1858, but it took the British one more year to eliminate robbers and dacoits. Even though the Mutiny had failed militarily, it had succeeded in ending the capricious and exploitative rule of the Company.

A new chapter

A state of peace was declared by Queen Victoria on July 8, 1859 which opened a new chapter leading to the independence of India within a century of the Mutiny. Questions are often raised on the Mutiny being the First War of India’s Independence and the role of Sikhs against the mutineers and in support of the British. To be objective, we must look at the India of that era. India was not a nation then and there was no national spirit. Marathas, Jats and Rajputs had been waging war against each other.

The Oudhis of Bengal Army had played a major role in the subjugation of the Sikh Raj by the British only eight years before the Mutiny. Purbeahs, as a part of the occupational force in Punjab, had looked down on the Punjabis including Sikhs as a people of a lower caste. The Mutiny was, in fact, the last gasp by the regional rajas, landlords and petty princes who fought in isolation. None of them made any attempt to coordinate their military efforts.

There was hardly any attempt to involve the sepoys of the Madras and Bombay Armies in the Mutiny. The choice of Meerut mutineers to appoint the Mughal as their Emperor could hardly attract the Sikhs to join them as the brutalities of the Mughals were still fresh in the Sikh psyche.

It is relevant to remember that Punjabi Muslims and Pathans fought against the Mughal at Delhi and the Begum of Lucknow while the Marathas of Bombay Presidency fought against Rani of Jhansi and other mutineers at Indore, Saugor, Jhansi and Agra. The Mutiny opened a new chapter for the British-Punjabi relationship, especially for Sikhs by creating employment opportunities for them. As mentioned earlier, the British had been impressed by the fighting abilities of the Sikhs during the Anglo-Sikh wars.

The Ferozepur Sikh Regiment was raised by Brasyer and was in Allahabad during May 1857 when he temporised with them, “Now we are on special duty, doing hard work, and in hot weather. Let us discard the cap and heavy clothing. Adopt your national dress and show them how Sikhs can fight.” Men were won over as Brasyer adopted their dress.

The Ferozepur Sikh, now 1 Sikh, from then onwards wear the red turban. For the outstanding work of 1 Sikh during the Mutiny at Lucknow and Kanpur, Havelock issued the famous Order of the Day— “Soldiers, your labours, your privations, your sufferings, your valour will not be forgotten by a grateful country.” These words are inscribed on his statue at Trafalgar Square, London and on the reverse “The Regiment of Brasyer’s Sikhs” is included amongst the units as the “Defenders of Lucknow”. XIV SIKH (Ferozepur Sikh) is the only unit of the Indian Army mentioned on a monument in England.

For their good services, each man of the unit was promoted to a higher grade and all subedars were granted the Indian Order of Merit First Class. Similarly, Hodson’s Horse Regiment has the unique distinction of Hodson and Risaldar Man Singh facing each other in their officer’s mess till today. General Wilson wrote after the victory at Delhi, “I believe our Sikhs and Gorkhas to be true as steel but not another native soldier is to be trusted.”

— Maj Gen Lachman Singh Lehl, PVSM, VrC, (retd), a distinguished military commander and historian, has also authored ‘Indian Force Strikes in East Pakistan’, ‘Victory in Bangladesh, ‘Missed Opportunities’ and co-authored ‘The Indian Army-A Brief History’(Centre for Armed Forces Historical Research- United Service Institution of India) Courtesy: WordSword Features & Media