The unprecedented rate of change and the level of uncertainty is outpacing good governance forcing problem-solving networks to upgrade through distributed connectivities. As international systems undergo tectonic shifts due to the disruptions of the pandemic and geopolitics realignments and the world gravitates towards a multipolar order, several opportunities open up for the wary and the alert.

To capitalise on this potential, governments will have to identify and insulate themselves from future shocks. However, this ability can only be achieved by an informed appreciation of the entire gamut of ‘unconventional threats’ that beleaguer humankind. This is a challenge that the Indian government must face upto if it wishes to profit from the opportunities.

Conceptual clarity

It is critical to prepare for threats that are extraordinary and not bound by convention. Although infrequent in nature and operating in contravention of dominant rules and societal norms, unconventional threats can metamorphose and acquire a more conventional hue with a change in the surrounding framework.

This is best illustrated by the employment of U boats (submarines) by the German Navy in World War 1. During the buildup to the war, the U.S. categorised unrestricted submarine warfare propounded by Germany as ‘acts of terror’ considering it unconventional, for it did not comply with the accepted rules of warfare.

Submarines, by their very design hunt by stealth and with no prior warning, and this strategy was used asymmetrically with deadly effect against British and American shipping. It was therefore, not surprising that in the next two decades, submarine warfare became a part of conventional naval operations and was extensively used by both sides in World War II.

Black swans, black jellyfish and black elephants

The ‘Black Swan Event’ popularised by Nassim Nicholas Taleb in his 2008 book, ‘The Black Swan: The Impact of the Highly Improbable,’ is today a commonly used metaphor. These are extremely rare events that cannot be predicted in advance and have large consequences, mostly negative. Standard forecasting tools fail to discern them and thus lull targets into a false sense of security. There are, however, two additional metaphors worth considering: the ‘Black Jellyfish’ and the ‘Black Elephant’.

The former refers to issues that are well-known and comprehensible but turn out to be complex and uncertain in the long run, with a long tail with a nasty sting on its tip! The latter represents a cross between the ‘Black Swan’ and ‘the elephant in the room,’ wherein the challenges are visible to everyone, but no one feels compelled to deal with them.

In other words, they signify the blind spots that arise due to cognitive bias, powerful institutional forces, short-sightedness and failure (or unwillingness) to read signals. In brief, an organisation’s inability to identify, comprehend and implement policies that address the ‘unknown’ and the ‘unpredictable’ can magnify the risk factors and incur high latent costs.

The threat landscape

Globalisation, while being recognised as the most progressive force in modern history, continues to draw flak for its lack of diffusion of wealth. This has triggered a wave of xenophobia, advocating protectionism and nationalistic rhetoric against greater global integration. Unfortunately, the institutional capacities to manage such global issues have not kept pace with the burgeoning complexities of modern society.

Although international establishments like the United Nations, International Monetary Fund, World Health Organisation and World Bank had arguably registered successes in the 20th century, they have increasingly failed to adapt to evolving realities in the 21st. Meanwhile, at the national level, politicians and policymakers have found it arduous to strike a balance between the compulsions of domestic politics and the benefits of universal connectivity.

A failure of governance has contributed to the proliferation of unconventional threats. Maya Tudor, an Oxford scholar, observes that the incapability of a state to meet the rising aspirations of its people in an interlinked world can further the rise of populism. When such populism fails to meet aspirations, it deteriorates into mobocracies and anarchies.

Rising income equalities, as measured by the Gini coefficient, represents another area of concern. Due to the growing automation and ‘uberisation’ of the world, along with the ascendancy of platform companies, wealth has become concentrated in the hands of a few. While disparities between countries may have reduced, the inequalities within nation-states have increased.

Such a yawning gap between the ‘haves’ and the ‘have-nots’ of society is particularly discernible in terms of income, wealth, education, social mobility, prosperity and political heft. If left unchecked, this can be a veritable recipe for disaster.

The escalating cost of education is equally perturbing. As higher learning becomes more expensive, driving it beyond the reach of many in society, social media networks find it easier to generate echo chambers and manipulate the human mind. As was recently observed in the context of the U.S. elections, online filter bubbles can polarise populations, erode trust in institutions, perpetuate uncertainty, and fuel grievances.

A failure of governance has contributed to the proliferation of unconventional threats.

Therefore, the weaponisation of information through deep fakes and disinformation should be actively resisted. Otherwise, it will provide opportunities for state and non-state actors to deter and coerce adversaries in an asymmetrical manner. Unless there is some form of accountability, a progressively expanding and unregulated information space can blur the difference between fact and opinion.

This makes individuals more susceptible to misinformation as well as radicalisation. More broadly, the agility and ultra-high-speed networks of interacting smart devices can be potentially exploited by malicious actors, thereby posing substantial challenges from a societal, organisational and personal point of view.

The poisoning of Artificial Intelligence (AI) defence systems can also not be discounted. As a growing number of security companies embrace AI for anticipating and detecting cyber-attacks, black hat hackers may attempt to corrupt these defences. Even though AI capabilities help to parse signals from noise, if they fall into the hands of the wrong people, they can be leveraged to launch sophisticated assaults. Generative adversarial networks (GAN) that pitch two neural networks against one another may be deployed to determine the algorithms of such AI models.

Finally, all governments need to account for the new classes of accidents and abuses that may be spawned by ‘21st-century technologies’. For the first time, the benefits of nanotechnology, robotics as well as genetic sciences are well within reach of individuals and small-scale actors. They are no longer required to build large facilities or acquire rare raw materials to derive value from them.

Knowledge alone can drive the application of such capabilities. In other words, it is important to acknowledge that weapons of mass destruction have been replaced by knowledge-enabled mass destruction. This destructive potential is further amplified by the power of self-replication.

Building robust supply chains that are resilient to disruptive factors is yet another need of the hour. The downfall of Ericsson in the early 2000s, owing to its failure in proactively managing supply chain risks, acts as a cautionary tale today. Indeed, most of the successful tech behemoths like Apple, Google, Intel or Dell, have retained their value since the 1990s through robust supply chain engineering.

Drawing on these lessons from history, it is absolutely critical to work with relevant partners and bolster supply chain risk management in other sectors.

Role of think tanks

Against this backdrop, it is imperative that governments and other non-partisan think tanks undertake research that forewarns policymakers and the strategic community about predictable surprises. By ideating about such unconventional threats and charting a roadmap for the future, a think tank can successfully transition into a ‘do tank’.

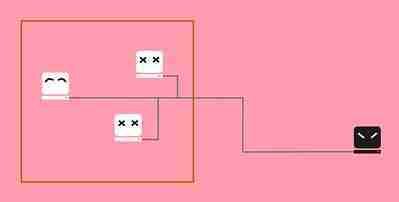

In 2015, the Synergia Foundation, a Bangalore-based strategic think tank had analysed the emerging hazards posed by the Internet of Things (IoT). Apart from examining the potential cyber threats for businesses and governments, it had formulated a framework for fostering dialogue at a global level and understanding the impact of digital threats to critical infrastructure and the IoT.

With the recently discovered cyber-attacks like SolarWinds in the U.S. and RedEcho in India, the need for such research has been clearly augmented. Even incidents like the Juspay data breach have underscored the need to incessantly monitor threats from the deep and dark web, a vulnerability that the think tank had first reported in 2014.

Resolving the tension between foresight and inherent uncertainty is the holy grail strategy for thwarting unconventional threats

As early as 2008, the Synergia Foundation had also foreseen that pandemics would pose serious threats to national security that goes beyond health. It had simulated the impact of an Avian flu attack for more than three hundred policymakers, business leaders and academics. Eleven years later, this prognosis has, sadly, been proven true.

With respect to the future of biosecurity, India and the rest of the world must be prepared to deal with threats that emanate from the thawing of the permafrost. As global warming continues at an unprecedented rate and parts of the planet witnesses record-breaking heatwaves, the Earth’s ancient and forgotten pathogens, which have been trapped or preserved in the permafrost for thousands of years, may re-emerge with new vigour. It is exceedingly important to ascertain such risks and devise strategies for countering them.

Forging ahead

Global governance is no longer about individual leaders plotting their own course. Rather, it entails a coalition of some of the finest and most avant-garde thinking in contemporary societies, which replaces competition with collaboration. High-performing organisations and individuals, both in the public and private sector, should strive to devise complementary solutions. The more valuable their contributions are, the stronger will their influence be.

At the end of the day, the rate of change and the level of uncertainty is such that it may outpace good governance. In light of this reality, it is critical for problem-solving networks to upgrade themselves by becoming more distributed and working in concert with each other. To accomplish this vision, a novel approach that places strategic adaptability at its core will be required in the days to come.

Resolving the tension between foresight and inherent uncertainty is the holy grail strategy for thwarting unconventional threats. Any inert failure to predict such risks can trigger chain reactions that unleash catastrophic consequences.