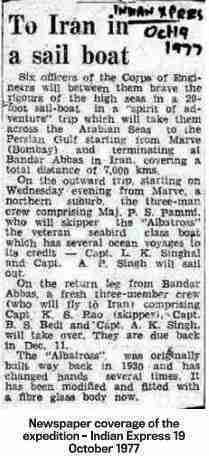

In early 1977, the Corps of Engineers planned a historic boat voyage across 3,500 kilometres of ocean in a small sailing boat. The vision was to circumnavigate the globe—a sailor’s ultimate dream, but funds were in short supply and getting official permissions a bugbear with our hierarchy and babus not yet open to such ideas.

Despite these constraints, Brig H K Kapoor, an inveterate sailor and erstwhile Secretary of the YAI, took on the challenge and the Corps of Engineers Sailing Club planned and conducted the historic voyage from Bombay to Iran and back in a 19-foot sailboat—the first time Indians sailed in a boat to foreign shores.

The Corps had two wooden Seabirds–the Albatross and Rajhans–both designed for inland and harbour sailing. The Albatross had been built by Garden Reach Workshop, Calcutta, in 1913! The boats had limited buoyancy, no cabin, engine, power source or navigational aids. The Sappers had earlier sailed these with the crew sleeping on her planks in the open and subsisting on whatever little food or water they could carry.

Getting ready

Preparations began for the expedition in April 1977 to sail from Marve in Mumbai to Bandar Abbas in Iran, through the Arabian Sea. The expedition was backed by Maj Gen PR Puri, Commandant CME Pune, who was an enthusiastic sportsman. Sailing a Seabird to Iran was a risky venture and all who were consulted on the project, including the Navy, termed it as suicidal! But that was part of the adventure and the Corps set out to modify the Albatross for the voyage.

The Albatross was as ready as feasible to sail in open seas, though the self-rightening test carried out in the Mulla River did not give the desired results as the boat turned turtle without warning

Under the creative guidance and design of the nominated Skipper, Major PS Pammi, Albatross received a 7-foot cabin, big enough to squeeze in two persons at a time on small bunks, though the headroom permitted only crawling in. A layer of fibreglass on the old wooden planks reinforced the hull. A Mariner’s Compass and Patent Log were fitted – purchased from the ‘Chor Bazaar’ in Mumbai, where parts of scrapped ships were hawked! The centre plate was bolted in a fixed position, to prevent it from falling off in the event of a capsize.

The Albatross was as ready as feasible to sail in open seas, though the self-rightening test carried out in the Mulla River did not give the desired results as the boat turned turtle without warning. This posed a grave risk for the crew, but none backed out from the voyage, despite being informed of the dangers by the organisers.

The Defence Food Research Laboratory, Bangalore, provided some of their newly developed pre-cooked packaged food for soldiers deployed in high altitude areas. These became our staple diet. M/S Swastik Rubber Company, Pune donated an inflatable life raft for emergency use, though how it was supposed to open if the boat turned turtle was anybody’s guess!

The Crew

For the outward journey, the skipper was Maj PS Pammi, accompanied by Capt LK Singhal and self. I was a young Captain then, doing the Degree Engineering Course at the CME as was Capt Singhal. For the return journey, Capt KS Rao was the Skipper, and he was accompanied by Capt PS Bedi and Capt AK Singh. We underwent some training in navigation at sea, at the Naval Training Team, NDA, and in the operation of High-Frequency Radio Sets.

The Albatross

Albatross was transported to Bombay by road and based at the Heavy Bridging Training Camp (HBTC), Marve, Bombay, an establishment, which imparted training on bridging in tidal waters. The out-going crew went a month earlier to test Albatross through training sails along the coast of Bombay. These sails also carried out at night, gave us an excellent opportunity to master boat handling in all weather conditions.

Before D-Day, we stocked Albatrosswith food, water, tools and spares. Alarmingly, the fully stocked boat had a freeboard of just 9 inches! Even in moderate wind and sea conditions, the boat would start taking in water over the sides. We would just have to bail out water manually whenever required.

In the evening of 19 October 1977, soon after high tide, Albatross set sail from Marve Creek on her voyage to Bandar Abbas.

After an extensive search in Chor Bazaar, we bought a hand-operated water pump, and thus had the satisfaction of having something more than just buckets and mugs. We also stocked the boat with shark repellant, as the waters approaching the Gulf of Hormuz were shark-infested. But the 9-inch freeboard did lead to more unanswered questions: would the sharks be able to peep inside?

From the Naval Hydrographic Office, we got the navigational charts and other publications, like pilots, navigation tables/books and geometrical instruments required for plotting our position at sea. The sextant materialised after another visit to the Chor Bazaar! We laminated the charts to make them waterproof.

We Set Sail

In the evening of 19 October 1977, soon after high tide, Albatross set sail from Marve Creek on her voyage to Bandar Abbas. We were given an emotional farewell with the presence of the ladies and Brig Kapoor against the backdrop of the setting sun. Our resolve was tested soon enough as within 24 hours strong North Westerly winds whipped up a choppy sea and presented us with an opportunity to test the hand-operated bailer. It was ineffective and we had to resort to the conventional exhausting technique of using a bucket for bailing out water.

The first day itself we sighted the Bombay High oil platforms with their flares visible from a considerable distance in the night. The wind and waves built up again on the third day, which made the going tough. Roaring seas crashed over the deck of Albatross, continuously for the next 48 hours.

We could neither sleep nor eat. Every breaking wave brought in water gushing into the boat, which we bailed out using buckets. The carefully stocked items were soon soaking wet and only a few navigational publications and charts, stored on the top shelves, escaped getting wet. We later learnt that the storm was the tail end of the cyclone, which had struck Orissa coast and had then crossed over the mainland.

This spell of heavy weather had its bright side. The boat made good progress of four to five knots, and by the morning of 24 October, we were only 10 nautical miles short of Dwarka. But sailing into the harbour against heavy coastal currents was not easy.

Winds dropped and we had to struggle for over 12 hours before we entered the fishing harbour in the falling dusk. Capt AK Singh was there to receive us. At Dwarka one of the two radio stations had been set up, the other being at Marve. The boat carried a small Army HF set, the TRA-922, used by the special forces. It was sturdy, with the added advantage of having a hand-cranked generator. With no electric power available, this was a Godsend.

Dwarka was a one-day halt. In between drying the food stock, publications and charts and repairing the damages sustained during the prolonged storm, we paid homage at the famous Dwarkadhish Temple. The voyage resumed in the morning of 26 October with the ebbing tide.

For the next three days, the boat struggled to make headway towards Karachi and progress was only 100 nautical miles. Strong currents pulled the boat into the Gulf of Kutch and it was only after we crossed the mouth of the Indus River delta, that the currents became favourable and winds picked up. The brown waters carrying the sediments from the Indus River were clearly visible even at that distance out at sea.

Around midnight, on the fourth day, when we were about 40 nautical miles short of Karachi, the boat came to a dead halt in the middle of the sea. We had been snared in a fishing net! The iron drop keel got stuck in the sturdy net and refused to budge. We struggled for a few hours in the darkness to cut the net but to no avail. Caution was required to not damage the hull.

Finally, using a combination of knives, barge pole and ropes, the boat was freed. Unfortunately, the spinner of the Patent Log got caught in the net and was lost. The spare spinner was fitted. The Log consisted of a spinning vane, which trailed from the stern, and its revolutions were mechanically converted to show the speed and distance covered. It was a crucial navigational aid required for plotting our position.

We entered Karachi harbour after dusk on 27 October. Using the Pilot to guide us to the embarkation jetty, we sailed through the harbour navigating by the flashing buoys. We were picked up by the hotel management of the Beach Luxury Hotel at Karachi, and to get a hotel bed was indeed a luxury after the narrow, wet, storm-tossed wooden plank on which we had been sleeping!

The avid Pakistani sailor, Mr Byram Avary, owned the hotel and he was also the Commodore of the Karachi Yacht Club. His offer to host the crew had been gladly accepted due to our limited budget. Each crew member had been given $200 traveller’s cheques before we started, which had to last us till our return home!

Surprisingly, no immigration formalities were done and we were told that the same would be completed the next morning. Our excitement further soared at the sight of seeing a television set in the room, a first for us – television had yet to make an appearance in India. Despite being exhausted, the television kept us engrossed till our eyes could remain open!

Accompanied by an officer of the Pakistan Navy, who remained with us as our ‘guide’ throughout our stay, we went off on a sightseeing-cum-shopping trip the next day. We received a warm welcome at the Karachi Yacht Club and an invite for a Pakistani dinner at the home of our ‘guide’, which we all greatly relished. The three-day halt at Karachi soon came to an end and we set sail again on 4 November 1977.

The next leg of the journey was with little or no wind. The boat was becalmed off Cape Monze for two days. We were however treated to the delightful sight of over 50 dolphins playing around the boat for hours in the flat seas. We also spotted a huge brownish-coloured whale about 20 feet long, which passed close to the boat, breathing noisily.

Due to adverse westerly winds, we decided to take advantage of the sea breeze phenomena closer to the coast and sailed a zig-zag course close to the Makran coast. The coastline was barren and hills dominated the skyline. Hardly any habitation or local fishermen were spotted in the area. Astola Island is an uninhabited island off the western Pakistani coastline, the only island in the northern Arabian Sea.

Known as the Island of Seven Hills, Satadip by Hindus, it is venerated due to the ruins of an ancient Kali temple located there. We had a remarkable sail past the island, with sea snakes in the water all around the boat as it sailed past in the light winds. Since seawater snakes are generally poisonous, we kept our fingers crossed that the winds did not pick up and splash water along with snakes inside the boat! Luckily, the passage was made safely and by evening the sea had cleared.

The Makran coast was rugged and dominated by sandy mountain ranges rising straight out of the sea. At night there were no lighthouses to guide sailors, and those that existed were non-functional. We had to rely on our navigation to plot our progress.

Our progress was reduced to about 20 nautical miles a day and it took a week’s sailing to cross the port of Gwadar, into Iran. Crossing the port during the night, we were surprised that hardly any lights were visible, though so much had been heard about its strategic importance. The complete lack of fishing activity along the long coastline continued to mystify us.

Arrival in Iran

Thirteen days out of Karachi we reached the entrance of the Gulf of Hormuz and the small port of Ras-e-Jask guarding its mouth. A number of large antennas were visible from the sea and we made a halt to clean up after the arduous sail from Karachi. We anchored in the Ras-e-Jask bay in the evening of 16 November 1977. The local fishermen braved the heavy surf to row out to us and take us ashore.

The local spoken language, Persian, was incomprehensible to us. And as none of the locals could speak English or Hindi, we had to spend the night at the local gendarme (police) station! Filthy clothes, haggard looks accompanied by beards made us look like smugglers!

A gendarme spotted the radio set, and his excitement appeared to be the last straw for the police! Fortunately, we were not put behind bars but asked to sit on the floor in one corner while the suspicious policemen eyed the ‘spies’ and the next course of action.

Around midnight, the gendarmes arrived with a Pakistani doctor serving at a nearby Imperial Coast Guard camp. The doctor acted as an interpreter and was able to extricate us from our predicament. Once the police learnt that it was an expedition by Indian Army officers, we were shifted to the camp, fed and lodged. A large contingent of Pakistani fishermen captured by the Coast Guard was to be taken by road to the regional headquarters at Bandar Abbas the next day. We were asked to accompany the party, though we were provided with a jeep for the journey.

A gendarme spotted the radio set, and his excitement appeared to be the last straw for the police! Fortunately, we were not put behind bars but asked to sit on the floor in one corner while the suspicious policemen eyed the ‘spies’ and the next course of action.

We met the Coast Guard regional commander and he welcomed us to Iran. After a brief interaction, we were on our way back to Ras-e-Jask. The effort of making the trip seemed puzzling, though we enjoyed the beautiful 700 km return drive along the coast of the Gulf of Hormuz. On our return, there was a celebratory dinner laid out by the hosts.

The meal was in traditional Arab style, eaten sitting on the floor from a large common salver. Well-rested and well-fed, we prepared to sail off the next morning. The Coast Guard went out of the way to replenish the boat’s supplies and provided us with a 20-litre tin can of petrol before we cast off on 20 November.

We sailed close to the Iranian shore where waters were shallower and outside the shipping lanes. We had been forewarned to avoid sailing close to the Omani coast as that could result in another visit to the lock-up! The second day out of Ras-e-Jask, we saw a few British naval ships, who changed course on spotting the Indian flag and sailed close by to say “Hello” to their tiny friend.

Finally, on the night of 22 November 1977, Albatross sailed into Bandar Abbas harbour and moored alongside the civil jetty the next morning. The relieving crew of Captains KS Rao, Bedi and AK Singh had reached earlier and had been keeping a watch for the boat as we were behind schedule.

There was no radio communication available with them, and hence they had been keeping a daily lookout. Till now the Ras-e-Jask incident was not known back home and it gave everyone a good laugh when narrated. As news spread about the arrival of an Indian sailboat, the local Indian population consisting mainly of doctors and engineers, turned up in large numbers with their families to see the boat, keeping us busy throughout the day.

The new crew got down to work without any delay. The boat, rigging and equipment was checked thoroughly. Minor repairs, especially to the keel and rudder which was damaged when the boat had got stuck in the fishing net off Dwarka, was carried out. The boat was stocked and made ready for the return voyage.

The adventures for us – the onward crew – did not end on reaching Bandar Abbas! Our flight to India was from Tehran, about 1,300 km across Iran by road. The next day we booked our tickets for an overnight bus. We were to contact the Defence Attaché at the Indian Embassy, Col BP Murgai, for assistance. We reached the Embassy lugging our limited baggage with considerable difficulty, as language was a major barrier in communicating with the locals.

We were in for a shock, as we learnt that we had missed the weekly flight for Bombay due to a delay in our arrival. We would have to wait for the next flight. Then the Embassy dropped another bombshell when they informed us that they were unable to provide any accommodation to us as we were not on an “official” visit to the country – we had been given “special leave” for the expedition. We were left nonplussed and literally on the road – with the balance of $200, after the Pakistan stopover, in our pockets!

We left the Embassy walking on the streets, wondering on how to survive in the city till our flight, which in those heady days of the Shah was among the most expensive cities of the world. Maj Pammi had done his homework well and was aware of the existence of a Gurdwara in Tehran.

We found the place; we learnt that Sikhs had been doing business in Iran since long and were among its richest residents. A short exchange by Maj Pammi on our predicament with the person managing the place, and we had a place to stay! And as is customary, it was free of charge. The person informed us that they only checked the antecedents of any visitors to ensure no illegals misused the facility.

The Gurdwara ensured us one meal. Black tea was a popular beverage and available everywhere, cheaply. Naans (flatbread) were subsidised by the government and available at every street corner. That became our staple diet during our stay in Tehran, with an occasional splurge on a can of Coke.

We could do limited sightseeing, within our walking range. Maj Pammi had studied Persian as a foreign language at NDA; he brushed up his forgotten lessons, though communication remained minimal. It was with some relief when the day arrived to catch our flight back to Bombay.

On return, the Albatross was accorded a fitting welcome at Bombay with the Navy sending out a ship with the family members to welcome the returning heroes out at sea. Albatross then sailed to the Gateway of India to a rousing welcome by the sailing community, friends & relatives and the organisers. The 7,000 km journey from 12 October to 23 December 1977 took 68 days to complete and was historic, in being the first voyage of an Indian sailboat touching foreign shores.

The aftermath

The expedition provided important lessons on long-distance sailing and proved invaluable for planning for the next voyage. Three crew of this six-member expedition undertook the circumnavigation on Trishna later, carrying forward the experience gained. They were Capt KS Rao,who became the Skipper, Capt AK Singh and self.

General TN Raina, Chief of Army Staff, while on a visit to Pune, met the onward crew of the Albatross to convey his congratulations; the boat was still on its return journey at that time. However, all crew members were subsequently called to Delhi and felicitated, including an invite for dinner at the Chief’s residence.

The crew members were conferred with the award of Sena Medal on Republic Day 1978. For me, the final upshot of this expedition was that I had been absent for a long period during the semester of the Degree Engineering Course. Despite my protestations to forestall the inevitable, I was relegated and lost six months. Now when one looks back on that decision, it appears to have been for my own good – I was able to sail for another six months from the cosy cocoon of the College!

The last (additional) semester I spent at the College was a whirlwind of sailing activities for me, to the extent that I was out sailing even during the final examinations of the 6th semester! A separate examination schedule was issued for me at a later date after my coursemates had already left the College, which I appeared for—an unnerving experience with one student and one invigilator in the huge examination hall! My scroll was handed over to me with my movement order!

End note

The Albatross now rests proudly at its alma mater – in the Open Air Museum of the College of Military Engineering, Pune. Though dwarfed by Trishna, its larger and more famous neighbour, it proudly holds its own place in the annals of the history of the Corps and the sailing fraternity of the country. After all, it is the one, which can claim to have set the Corps, and India, on the road (water?) to bluewater sailing!