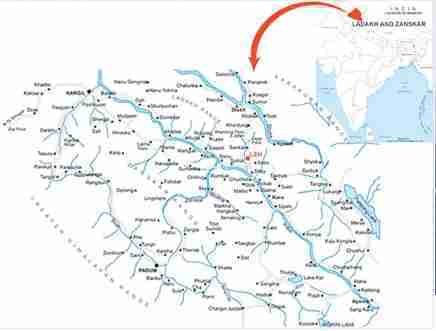

Zanskar is a sub- division of Kargil district of Ladakh Region, the cold desert of India. It is a sparsely populated B u d d h i s t dominated area which has the distinction of being one of the three oldest tehsils of Ladakh. It is strategically located since it is adjoining the Kishtwar area of Jammu province and the other neighbouring state of Himachal Pradesh. It is connected by a 250 km long single mountainous, high altitude road that remains cut off from rest of the world including its district headquarters at Kargil for six months in a year. The road connects the Kargil town and Padum, the sub-divisional headquarters and is the only lifeline for the two tehsils of Sankoo and Zanskar. Its average elevation is 12000 feet. Zanskar is a high altitude semi-desert lying on the Northern flank of the Great Himalayan Range.

Zanskar is the most isolated part of Trans Himalaya region. Pleasant climate, beautiful landscape, snow-capped Himalayan Mountains and sparking rivers make Zanskar a perfect holiday destination. Buddhism is the religion of the majority except a few Sunni Muslims residing in Padum. The Valley is also dotted with numerous historical and ancient gompas. The Valley is bestowed with abundant natural beauty but its remoteness has kept it underdeveloped, isolated and away from the tourist map.

Sheikh Abdullah during his first tenure carved the Muslim majority Doda District out of the Bhaderwah jagir and during his second tenure created another Muslim majority district by dividing the Ladakh region on religious lines in order to counter the growing influence of the Buddhists in the region who had been opposed to inclusion of Ladakh with Kashmir during the administrative reorganisation of the state by the Sheikh and his party, National Conference. Zanskar sub-division was made part of Muslim-majority Kargil district on latter’s formation in 1979.

Historically, Ladakh had become part of the Dogra Empire a decade before Kashmir joined it in 1846 after the Treaty of Amritsar, thus creating the princely state of Jammu & Kashmir. The Dogra rulers had kept the frontier areas including Ladakh and Gilgit as separate administrative units known as Frontier Districts comprising of Wazarats of Ladakh & Gilgit and Frontier ilaqas. As per census of 1941, last census before the accession, Ladakh Wazarat consisted of three tehsils of Leh, Skardu & Kargil while Kashmir province consisted of South Kashmir, North Kashmir and Muzaffarabad. After Skardu came under illegal occupation of Pakistan as a consequence of Pak aggression of 1947- 48, Zanskar was made the third tehsil of the region. Thus, Ladakh region had an independent identity prior to its reorganisation by the Constituent Assembly which made it as a district of Kashmir.

The Ladakhis opposed the Kashmiri hegemony and were unhappy with the new system of governance when power was virtually transferred from Maharaja Hari Singh to Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah, since the area was distinct from Kashmir geographically, culturally and religiously. The Muslim population of Ladakh was mainly Shia and was concentrated in Kargil tehsil, a minuscule Sunni population formed part of the Buddhist pre-dominant Zanskar tehsil.

Sheikh Abdullah was a strong advocate of unitary system. He believed in “One organisation (National Conference), One Leader (Sheikh Abdullah) and One Programme (Naya Kashmir).” Accordingly, the Constituent Assembly comprising solely the members from his party, National Conference, conceived the unitary system of governance with Kashmir as the centre of power. These leaders failed to recognise the fact that the state no more was glued together by the monarchical system but consisted of three distinct regions which were not homogeneous but heterogeneous and also had distinct geographical barriers dividing them topographically as well. However, their lust for power and urge for “Kashmiri Muslim Dominance” made them blind to the ground realities and aspirations of the other two regions. With the clubbing of Ladakh region with Kashmir province, the Ladakhis began to feel neglected and denounced virtual “Kashmiri Rule.” As the time passed the rift widened, alienation grew and the demand for direct central rule gained momentum under the umbrella of Ladakh Buddhist Association (LBA).

The bifurcation of Ladakh and formation of Muslim-dominated Kargil district was a part of Sheikh Abdullah’s strategy to counter the growing demand for direct central rule. A big mischief was also played with the people of Zanskar at this stage. It was de-linked from the Buddhist Leh and grouped with the newly formed Muslim district of Kargil. It was conceived to be a master stroke because it also divided the Buddhist population since Zanskar did not have any direct road link with Leh except via Kargil. There is a traditional route known as the Chaddar Trek which connects Leh with Padum which is feasible only during the harsh winter period. An all-weather road is being constructed along the trek route but is nowhere near completion. Another road which emanates from Darcha on Manali-Leh National Highway is also under construction but has failed to meet repeated deadlines of completion and is now likely to be completed by 2021. When completed, Road Darcha-Padum-Neemoo-Leh will be strategically very important.

The region of Zanskar has been marginalised in terms of all developmental needs. The region of Zanskar comprises over half of Kargil District in terms of area, which is 7,000 square km but out of the total population of 1,40,802, Zanskar has only around 20,000. Internally, it is disconnected to the other areas of Ladakh like Leh and Kargil, which are administrative centres of the region, and externally it is disconnected to the region outside Ladakh. While rest of the country is preparing for a digital revolution, the marginalised population of Zanskar is still struggling to get basic road connectivity.

Ever since Zanskar was grouped with Kargil district, it has been struggling to get equal share of resources from the administration. While Zanskar makes up half of the area of Kargil District, it is barely represented at the upper echelons of the bureaucracy in Kargil or Srinagar. It lacks even the basic infrastructure of health care and education. Thus isolation, remoteness and vastness of the area coupled with a partisan administrative apparatus sitting far away at Kargil has forced the local residents, particularly the youth to demand a separate district status. Though it is one of the oldest Tehsils of the state, yet it has been deprived the district status which it deserves due to its peculiar geographic location.

Another major injustice was done to this region when Zanskar assembly constituency was notified by including the Muslim dominated area of Sankoo of Suru Valley alongwith sparsely populated Zanskar Valley, a deliberate attempt by Kashmir-centric administration at gerrymandering. To compound the problem further Rangdum, the last village of Zanskar linking with Kargil was detached and clubbed with Kargil constituency. Though, on paper Zanskar constituency exists it has never been represented by a local Buddhist because of apparent population skew. Only ‘outsiders’ have been representing the constituency defying the basic principle of representation and ignoring the interests of the people of Zanskar valley. To give true representation to the people of Zanskar Valley there is a need for a fresh delimitation of a new assembly constituency giving representation to Zanskar sub-division by delinking Sankoo and reverting back Rangdum.

Thus, the people of Zanskar sub- division have been victims of two grave injustices; administrative neglect due to its clubbing with Kargil district in 1979 and political marginalisation through gerrymandering of Zanskar assembly constituency vide 20th Amendment Act of 1988. The population dynamics of the Constituency is such that a native of Zanskar sub-division can never be elected and the region cannot have its own voice in the state legislative assembly adding to its woes of remoteness and consequent lack of development.

As usual the genuine demands of the Zanskaris have met with stiff resistance from certain sections in Kargil both on political and religious grounds. However, the people of Kargil easily forget the communal touch they gave to the government’s decision to grant divisional status to Ladakh and insisted on rotational location of the divisional headquarters on six-monthly basis, in which they were successful. Then, why should they object to the aspirations of the people of Zanskar who are vying for a separate district and assembly constituency delinking it from densely populated Muslim-dominated Suru Valley.

There are some opposing it on administrative grounds as well stating that it is very sparsely populated for upgradation to a district status. The least populated district in India is Upper Dibang in Arunachal Pradesh which has a population of approximately 7,200, which is much less than the population of Zanskar. Aren’t the Zanskaris entitled to dream of better representation in the state assembly and holistic development of their neglected but strategically important region? Zanskar deserves justice and the injustice done in 1979 & 1988 needs to be undone.

Brig Anil Gupta is a Jammu based political commentator, columnist, security and strategic analyst. He can be contacted at anil5457@gmail.com