This article has been taken from the personal documents of Air Vice Marshal Chandan Singh, MVC, AVSM, VrC, who played a pivotal role in the Liberation War. Indeed, the swiftness with which ground operations were conducted by IV Corps, was in great measure due to the skilful use of helicopters by AVM Chandan Singh and his dynamic Corps Commander, Lt Gen Sagat Singh.

To this duo, must credit be given for ensuring the war ended in 13 days. Thanks are due to Maj Chandrakant Singh, VrC, himself a veteran of the Liberation War, for making the documents available for publication and the photographs published in this article. Air Vice-Marshal Chandan Singh passed away on 29 March 2020, Aged 94 years. He remains an iconic figure and a role model, not only for the Indian Air Force but for the entirety of the Indian Armed Forces.

—Editor

Ferrying men and material in support of ground operations.

In 1971, I was posted as Commander at the IAF Station, Jorhat. We had two transport squadrons, a flight of Mi4 helicopters and detachment of Hunters and Gnats. The transport squadrons provided logistic support to the Army posts in the North East States along with the Tibet and Burma (Myanmar) borders.

They also supported the Army formations deployed in counterinsurgency role in Nagaland, Manipur and Mizo Hills. The helicopter unit provided communication support and casualty evacuation facility to isolated army posts, which in many cases were several days march on foot from the nearest road head. Maintenance of these posts was by the para dropping of supplies including rations.

As there was neither electricity nor refrigeration facilities at these remote posts it was a common sight to see a dozen or so sheep and goats (in-service terminology MOH or meat on hoof) crammed tightly into a wooden crate and fastened to a parachute and loaded into the Dakotas for dropping over the posts.

Many of the animals would be injured and nearly all would become blind for some reason. Before animal rights activists start howling in protest, it must be remembered that our men at these post had no fresh vegetables for months on end and had to subsist on wheat flour, rice, dal, potatoes and onions. MOH and rum were not luxuries, but essential survival rations.

Jorhat is located on the southern bank of the Brahmaputra River in North East Assam. It is in the middle of the tea country where the finest teas are grown; the true connoisseurs prefer Assam tea to that from Darjeeling, for its full body and rich taste.

The tea planters clubs where we were all honorary members provided a welcome social diversion. The airfield was one of several dozen built by the British and Americans during World War II to support their operations against the Japanese in Burma and also as bases for transport aircraft which flew over

the Hump carrying supplies for the Chinese for their war effort against the same enemy. Bases such as these supported the Chindits and Merrill’s Marauders, which operated behind enemy lines. The people of the plains are mainly Assamese, but diverse tribal people of different racial and linguistic groups inhabit the remote valleys and hills.

Having several helicopters in my command, I visited their settlements as often as I could to show the Indian flag and also because their lives and customs fascinated me.

When the trouble in East Pakistan started, I had no role as no task had yet been given to the IAF. Events moved so fast from 25 March 1971, when Sheikh Mujibur Rahman was arrested and Major Ziaur Rahman announced the declaration of Independence on Radio Chittagong that the Government of India and the Service Headquarters were taken completely by surprise and were slow to react.

No contingency plans existed to cater to face such a situation. My involvement started in the Bangladesh War sometime in July 1971. The Air Officer Commanding in Chief (AOC-in-C), Eastern Air Command, Air Marshal Devan, tasked me to take charge of the training of about a dozen Bengali pilots and a hundred airmen who had defected from the Pakistan Air Force.

I was to create a nucleus for the future Bangladesh Air Force. The aim was to build up to at least one squadron strength, but sufficient pilots and aircraft were not available. I was given two Otter passenger aircraft and one Alouette helicopter for training.

The Bangladeshi pilots had to eventually be made operational on Hunters, but this was a long-term task and at that time, we found the pilots and the airmen under-qualified. I started with training the pilots on Otters in night time ultra-low level flying. I moved the Bengali pilots and airmen to a satellite field at Dimapur, for here I could train them without interruption of our operations at Jorhat.

Anticipating that with the aircraft provided we could only operate at night against the enemy, I started them on low-level night-time flying training. This type of flying, called horizon flying is both difficult and hazardous. I had trained on this type of flying with the CIA in 1963 and was the only such qualified pilot in the IAF. This training paid great dividends and when the war broke out in December, the Bengali pilots performed magnificently.

The aircraft were modified and fitted with two chutes to drop 25- pound bombs and two rocket pods each carrying 14 rockets. In addition, a light machine gun was mounted in the cockpit behind the pilot. Within one month, we trained five pilots to fly solo in all roles of bombing and rocketing at night.

The enthusiasm of the pilots and ground crew was remarkable and they learnt quickly. This was fortunate, for, at the end of November, the AOC-in-C asked me to move with my small Bangladesh Air Force to Kumbhigram and launch operations before the war started. Kumbhigram is in the Cachar District in South Assam, close to Bangladesh.

We arrived at Kumbhigram on the morning of 2 December. IV Corps had already launched its offensive in East Pakistan and heavy fighting was going on over a frontage of more than five

hundred km, all the way from the borders of Meghalaya to the Mizo Hills. I was ordered to launch a bombing raid on the fuel storage tanks at Chittagong and Narayanganj. That night, under a brilliant moon the first sorties took off, the Alouette piloted by Flying Officer Alam to Narayanganj and one Otter piloted by Squadron Leader Sultan to Chittagong. An hour and a half later I took off in the other Otter and flew towards Chittagong where I saw a bright glow on the horizon towards the harbour which indicated that Sultan had been successful in his mission.

I then turned northwest towards Dhaka and saw another glow coming from the vicinity of Narayanganj, confirming that Alam in his little Alouette too had accomplished his mission. In the overall plan, our contribution may have been small but it did a whale of good to the Bengalis and had a very negative effect on the Pakistanis. It brought the war deep into East Pakistan, conveying to the enemy that the gloves were off and there was to be no turning back.

Later in the morning, I was told that The Pakistan Air Force had launched pre-emptive strikes on some of our airfields on the Western Front. These, however, did little or no damage as we were prepared for them, having learnt our lessons from the Israeli actions on Egypt in 1967 when they destroyed the entire Egyptian Air Force in one morning. Before proceeding further, I would like to mention the gallantry and enthusiasm of the Bangladeshi pilot’s Sultan, Alam and Ali.

They continued with their bombing and strafing runs throughout the war in support of IV Corps operations with whose actions I now got involved.

On 3 December, I went to headquarter of IV Corps at Teliamura in Agartala, to meet the Corps Commander, Lieutenant General Sagat Singh. I arrived there that afternoon but could not meet him as he was out visiting troops. I met him late that evening as he arrived and stayed the night; it was quite an experience. He was full of energy, dynamism and go.

Over several large whiskeys, he asked as to what our little Bangladesh Air Force could do. As a starter, he asked me to leave Kumbhigram and move closer to any one of the border airstrips at Kailashahar, Kamalpur of Khowai. I selected Kailashahar as that was where the action was.

He asked me to target transport movement, lines of communication and troop concentrations and if possible destroy a bridge or two. He did not have much time so I could not discuss details with him. In any case, I didn’t have much of an air force.

I arrived at Kailashahar with my little Bangladesh Air Force (BAF) on the morning of 4 December and mounted a total of thirty-six sorties on 4th, 5th, and 6th, mostly disrupting the lines of communications between Munshi Bazaar, Fenchuganj and Brahmanbaria.

I am not sure of the success we had with these three aircraft, but on the sorties, I was on, we did attack road transport and convoys. On my sorties with Flt Lt Singhla and Flt Lt Sultan of the BAF, we managed to hit three troop transports. My log confirms two transport’s totally destroyed; in the other missions, it states targets hit but results not known. I am sure the sorties would have had similar results.

On the fifth evening, General Sagat Singh told me over the phone to call on General Krishna Rao, GOC 8 Mountain Division and inquire if I could be of help in his operations. I called on him the next morning. That particular day a battle had been raging at Alinagar Tea Estate near Shamshernagar airfield in East Pakistan. I had been observing the progress of the battle from Kailashahar and when the guns fell silent, I got airborne and landed at Shamshernagar.

I had thought of using the Shamshernagar airfield to move further forward but found that the airstrip had been so badly cratered by our shelling that it was unsuitable even for helicopters. There were craters even in the parking area. Nevertheless, we landed there and commandeering an army jeep, I asked the driver to take me to the divisional headquarters. I noticed a large number of bunkers and trenches damaged by our fire.

Headquarter 8 Mountain Division was in the centre of the tea estate and in a clearing was parked the Division Commander’s caravan in which he stayed and had his office. Next to it, there was a bit of an open ground where a helicopter could land.

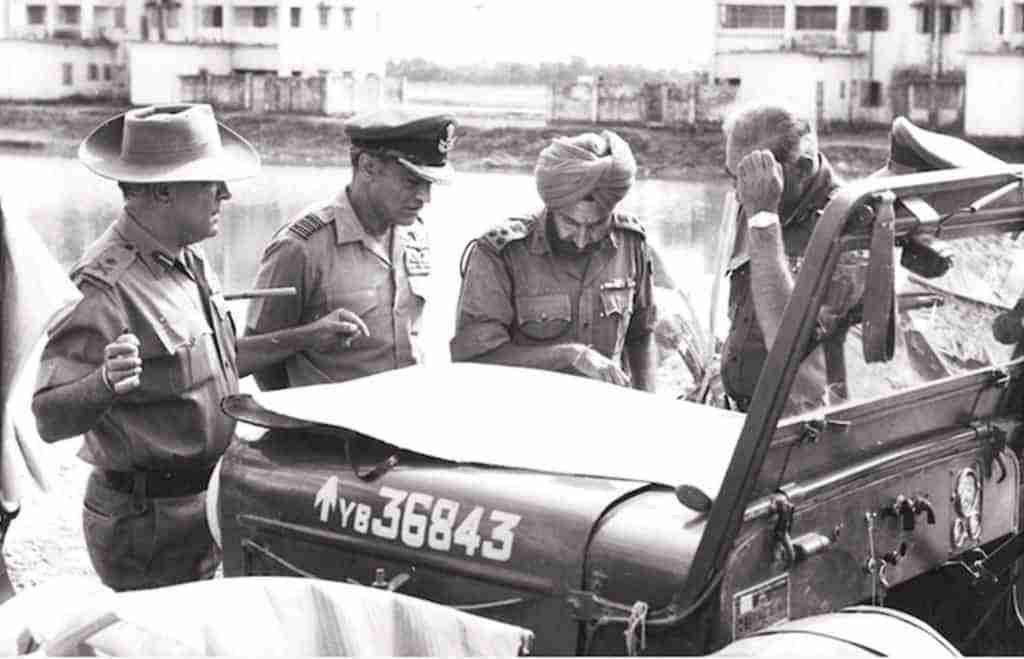

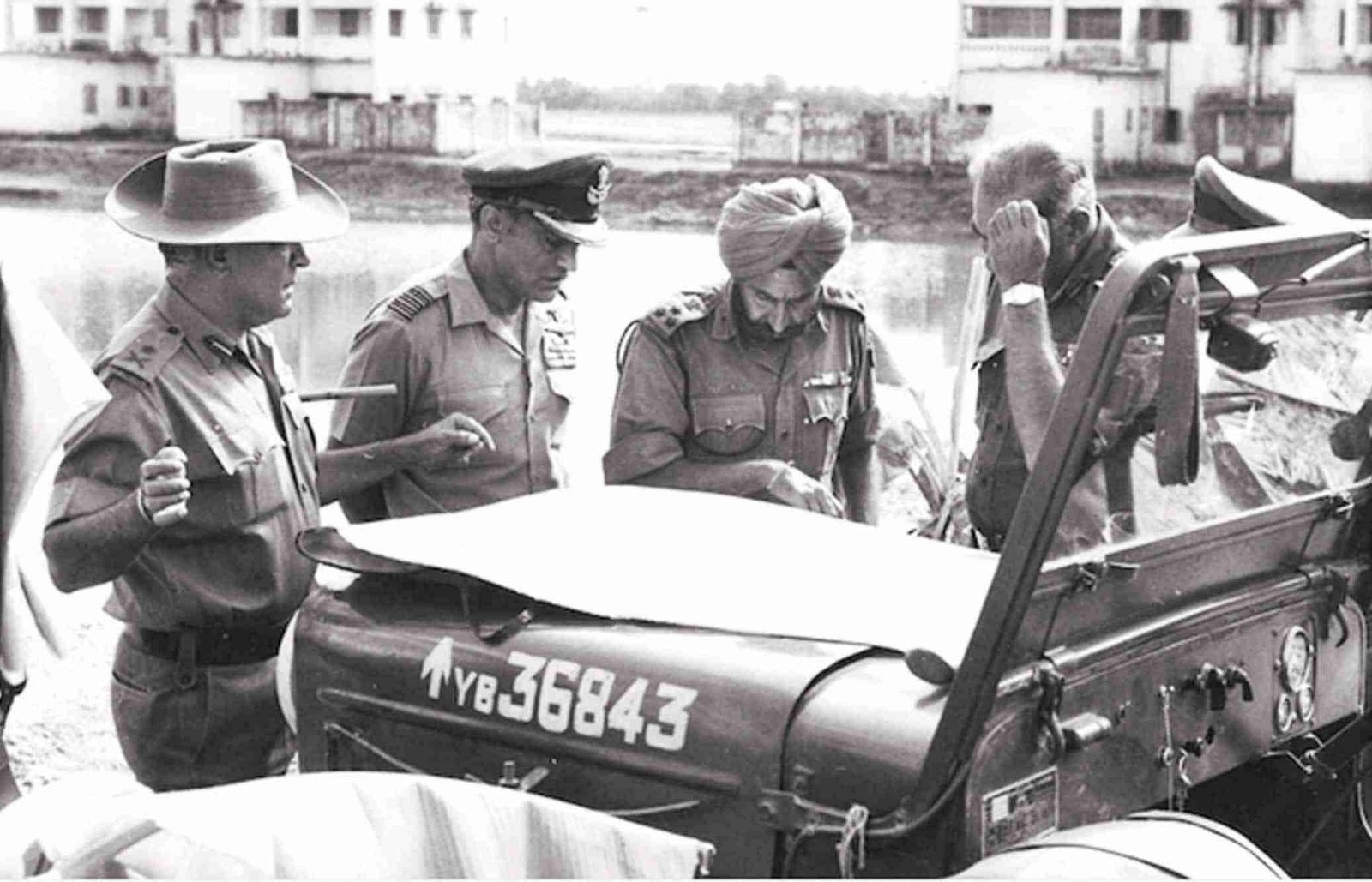

As soon as I met General Rao, a helicopter landed on the open ground and out emerged General Sagat Singh. The IV Corps Commander had a half-hour discussion with General Krishna Rao and then I was called in and told to act as the eyes and ears of 8 Mountain Division. I was also told that some more Mi4 helicopters were arriving and I was to take charge of them too.

A little later, on the same morning, General Sagat Singh called me up again and said that the enemy at Sylhet wanted to surrender and since our ground forces were not close enough I was to fly to Sylhet, accept the surrender and bring him the Instrument of Surrender. It was a great moment and an honour and I was thrilled that he had chosen me for this task.

On the seventh morning, I got airborne and went towards Sylhet where I saw a dead town with not a soul-stirring in the open. I did two orbits around the town and then flew to the Sylhet airport expecting the Pakistanis to be lined up, waiting to surrender, but saw no one. I had half a mind to return but then against my instincts and better judgment decided to land thinking that the enemy troops were hiding undercover and would emerge once they saw the helicopter land.

I was just about to touch down when I heard the rattle of machine guns from all directions and bullets striking the fuselage of the helicopter. This time I followed my instinct. I came upon the collective, opened the throttle and got away flying low level between the trees and out of range of enemy fire. I did not know the extent of the damage but managed to climb up to 4000 ft.

I once again observed the airfield and saw no movement and had half a mind to try and land once again. Better sense prevailed and I returned to Shamshernagar. I then drove to the divisional headquarter. General Sagat Singh too had come there, which gave me an opportunity to accost him.

“Sir”, I said to the IV Corps Commander, “I have just returned from Sylhet but the only reception I got there was a hail of bullets and my helicopter is perforated with bullet holes”.

General Sagat Singh did not bat an eyelid. It made no difference to him whether I was hit or not.

“In that case,” he said, “we launch a heliborne operation against Sylhet”. He did not express any sympathy or even apologise that the information about the garrison wanting to surrender was incorrect. Sagat was that very rare breed of men who had only the mission in mind regardless of all else. “Now that you are with us,” he said, “you stay with us”.

He informed me that at this very moment, 110 Helicopter Squadron under Squadron Leader Sandhu was landing at Kailashahar and I was to take charge of them. He said that by 1200 hours this very day (7 December), I was to go to Kulaura and pick up Brigadier CA (Bunty) Quinn, Commander 59 Mountain Brigade, then go to Sylhet and select a landing place for the helicopters. After that, I was to use the newly arrived helicopters to launch the operation.

As ordered, I went over to Brigadier Quinn, whose troops had just come out of the Battle of Ghazipur, a couple of kilometres from Kulaura. Kulaura is a small railway station with a couple of sheds, a school building and some barrack-like structures.

One of Bunty Quinn’s battalions, 4/5 Gurkha Rifles was resting in the buildings after having suffered heavy casualties in the battle of Ghazipur. When I went to meet the Commanding Officer of the battalion, he said that all his officers were casualties and there were only himself and one other officer who were fit to carry out operations, implying thereby that his unit could not undertake operations immediately.

I told the Brigade Commander that I did not know whether he had received these orders yet, but my orders from the Corps Commander and the Division Commander were explicit. “I must start mounting the heliborne operation with your troops on board at 1200 hours and complete the operation by sunset,” I told him. I added that time was of great essence, and whatever troops they had were to be reorganised quickly as this was a new operation.

Bunty Quinn also stated that it would be very difficult for these troops. He said that we would light up at the paddy fields at Kulaura and have unidirectional glim lamps at Sylhet. I detailed Squadron Leader Chowdhry of the Dakota Group at Kailashahar to be responsible for the ground facilities at Sylhet.

The plan was for the Bangladesh pilots to provide a protective umbrella in the Otters, a difficult task but still good deterrence. The troops would be lifted with six Mi4 helicopters as another one had joined us from Mizo Hills. I was in one of the Alouettes with Singhla flying protective air cover and had a grand time firing rockets and machine guns at Pakistani machine gun positions, which revealed their location whenever they fired tracer rounds at us.

I do not know how much damage we did but as the night progressed, the firing became less intense. Singhla and the Bangladeshi pilots flew all night, returning only to refuel and rearm. Initially, I had flown protective air cover but later did two sorties on the Mi4s. All was going well and I was keeping abreast of the happenings on the radio, but at 0300 hours, I received information that one of the Mi4s was badly hit and grounded at Sylhet.

I told the pilot not to attempt to recoup the helicopter but to stay with the ground troops and we would evacuate him in the morning. One more aircraft force landed en-route, possibly due to bad servicing or sheer engine fatigue or enemy action. So now, out of six Mi4, we had just four left. It was only in the morning that I could have a look at our machines, which we collected at Kailashahar for serving and regrouping.

I then took an armed Alouette to have a look at the two grounded helicopters. The one that landed en route had engine trouble but could be repaired in situ. I noted the spare parts required and told the crew to stay on. The other helicopter was badly damaged and it was not possible to repair it immediately as the Gurkhas were still engaged with the enemy half a kilometre away. We, therefore, had to abandon it for the time being. The other one we had repaired and retrieved in a couple of hours followed soon by the one at Sylhet.

The Heliborne operation carried on during the day and we were now flying in the reinforcement battalion. In the meantime, I received a note from General Sagat Singh congratulating us and urging us to continue. The General, once having got the enemy by the throat, was not going to let him go! By now, though exhausted, we had a sense of satisfaction at a mission well done.

Our air effort was now augmented with MIG 21s from Tezpur. Having achieved complete mastery of the sky, the MiGs were hammering away at the enemy’s lines of communication all around Sylhet. I, with my Bangladesh Air Force, had a field day bombing and strafing enemy convoys moving from Maulvi Bazar and other places to reinforce Sylhet.

Those reinforcing troops had to abandon their vehicles and start moving in total disarray on foot, where they fell prey to the Mukti Bahini boys and our own advancing troops.

So swift was the advance of ground troops that information on their advance and locations could not reach the Joint Operations Rooms and our planes sometimes strafed our own forces. On 12 December, 4 Guards was strafed, my own MiGs. Shaheed, who was the Forward Air Controller with the battalion, contacted the pilot on the radio and informed him of his mistake, but the pilot could not believe that our troops were that far forward.

He thought the Pakistanis had broken into our radio frequency and were speaking to him. Fortunately, Shaheed convinced the pilot to pull away and the only casualty was the heel of the boot of the company commander, Major Marwah, which he has preserved.

By the end of 8 December when the mission was completed, our small band of six Mi4s, two Otters and one Alouette had carried out twenty-two sorties on 7 December, thirty-four sorties on night 7/8 December and ten sorties on 8 December. Considering the fact that two or three aircraft were always out of commission at any one time it meant that each aircraft had carried out twelve sorties on an average.

It was indeed a tremendous achievement. We carried twelve hundred troops and ten tons of stores and equipment in about twenty-four hours of nonstop flying, enabling the Army to achieve its objectives. The helicopters encountered heavy small arms fire during the operations and all helicopters had the fuselages punctured like garden watering cans, but no pilot, Indian or

Bangladeshi, gave any thought to the danger and carried on with their mission, something that makes me proud to this day. General Sagat Singh handsomely acknowledged the dedication and gallantry of all the pilots.

Early on 8th morning, I decided that I must get official sanction for the operations from AOC in C Eastern Air Command so I decided to fly to Shillong via Jorhat to get a couple of hours of rest and change of uniform for my meeting. At Jorhat, I received a call from the Senior Air Staff Officer congratulating me for the success of the operation and asking me to get back to Kailashahar.

I took this as approval and so the anxiety of being hauled over coals for undertaking a mission, which had no sanction from higher authorities, was removed from my mind. I returned to the war zone ready to undertake anything, which Gen Sagat Singh may conjure up. He was a magician and conjurer who could handle half a dozen battles at the same time. He not only had the enemy guessing about his moves and plans but even we could never guess what and where his next move would be.

The Sylhet operation was unique as it was the first time in the history of India that such kind and magnitude of operation had been undertaken. It was also unique because it was not pre-planned. The Corps Commander saw an opportunity, seized it and launched the operation, knowing that the air resources were inadequate but we would deliver.

At the commencement of the operation, neither Bunty Quinn nor I had a clue about enemy disposition and strength but even the enemy could not quantify us and take countermeasures for we had achieved total surprise and speed, which is the essence of heliborne operations.

The impact of the operation was that it opened the eyes of the Army and Air Commanders to the employment of helicopters as the answer to the problems posed by the terrain in Bangladesh and made more intractable by the destruction of nearly all bridges by the Pakistanis and Freedom Fighters. While commanders had planned to use the Mi4s in an operational role, sanction was accorded for only a company-sized operation. At no stage was an operation of this magnitude visualised.

The Sylhet operation helped us iron out operational procedures and lighting of landing and take-off pads. Such operations require total understanding and cooperation between the Army and Air Force, not just at the level of headquarters but also between the pilots and the assault troops. This we achieved at Sylhet. The next step was the crossing of the Meghna.