The origins of Secunderabad are closely intertwined with the history of eighteenth century Deccan, and in particular with the arrival of the military forces of the East India Company to fortify the fluctuating relationship between the Nizam and the British. It was essentially a military cantonment whose foundations were laid in the politics of Deccan; with a frail Nizam, the dexterous Tipu Sultan, declining French influence and the expanding British territory under Lord Wellesley, British Governor-General in India from 1798 to 1805, most famously known for introducing the novel doctrine of Subsidiary Alliance.

In 1789, Lord Cornwallis concluded a treaty with Nizam Ali by which the East India Company agreed to provide troops to the Nizam whenever he required them. Nizam in turn agreed to disband the French troops in his service. The British outmanoeuvred the wily Tipu Sultan and persuaded the Nizam, not to join forces with Tipu who aimed to ‘drive the firangees out of Deccan’. It was a major diplomatic coup as Tipu was not short of followers in the territories of Nizam. In fact, his followers had built a bridge on Musi River near Golconda Fort, named Tipu Khan Bridge, apparently to welcome the Sultan if he rode in Hyderabad to join his co-religionist Nizam. But in 1799, Tipu was killed during the storming of his river island fortress of Seringapatam.

The end of the Mysore War buoyed the British. They insisted on cementing relations with Hyderabad. Nizam Ali Khan, after much persuasion and skilful lobbying by the British Resident at the court of Nizam, Major James Achilles Kirkpatrick, finally signed the Subsidiary Treaty in October 1800 (finalised in 1798) with the Honourable East India Company. This treaty of General Offensive and Defensive Alliance was popularly known as the Treaty of Subsidiary Alliance and it stipulated positioning of a military force, called Subsidiary Force, at Hyderabad. For the maintenance of this force, the Nizam ceded to the East India Company all the territories acquired by him, during the Mysore War, south of the river Tungabhadra. These areas came to be known as the Ceded Districts, now called Rayalaseema.

The Era of Nizams

Hyderabad was established in 1591 by Muhammad Quli Qutb Shah. The Qutb Shahis were Shias, who named their new capital Hyderabad after Ali, Hyder being one of his names. It remained under the rule of the Qutb Shahi dynasty for nearly a century before the Mughals captured the region. In 1724, Mughal viceroy Asif Jah I, also called Nizam ul-Mulk, declared his sovereignty and created his own dynasty, known as the Nizams of Hyderabad. He was succeeded by his fourth son, Ali Khan, Asaf Jah II, but not before Ali Khan dethroned and imprisoned his brother Salabat Jung in 1762. Nawab Mir Nizam Ali Khan was the father of Sikander Jah, who succeeded him in 1803, and after whom the upcoming tented cantonment city, Secunderabad was named. By the time, Sikander Jah or more properly Nawab Mir Akbar Ali Khan, Sikander Jah, Asaf Jah III, died in May 1829, the city named after him – Secunderabad – was thriving.

While William Dalrymple in White Mughals has vividly recreated the negotiations and politics behind the treaty, not to mention the tragic love story between James Kirkpatrick and Khair un-Nissa, the great niece of the Nizam’s Prime Minister; excellent accounts of the new British cantonment, to be named Secunderabad, coming up ten miles to the north of the old city just over the Banjara Hills, have been given by Mountstuart Elphinstone and Edward Strachey, fellow travellers and civil servants of the East India Company, who visited Hyderabad in 1801 while enroute to taking up a job with the East India Company in Poona.

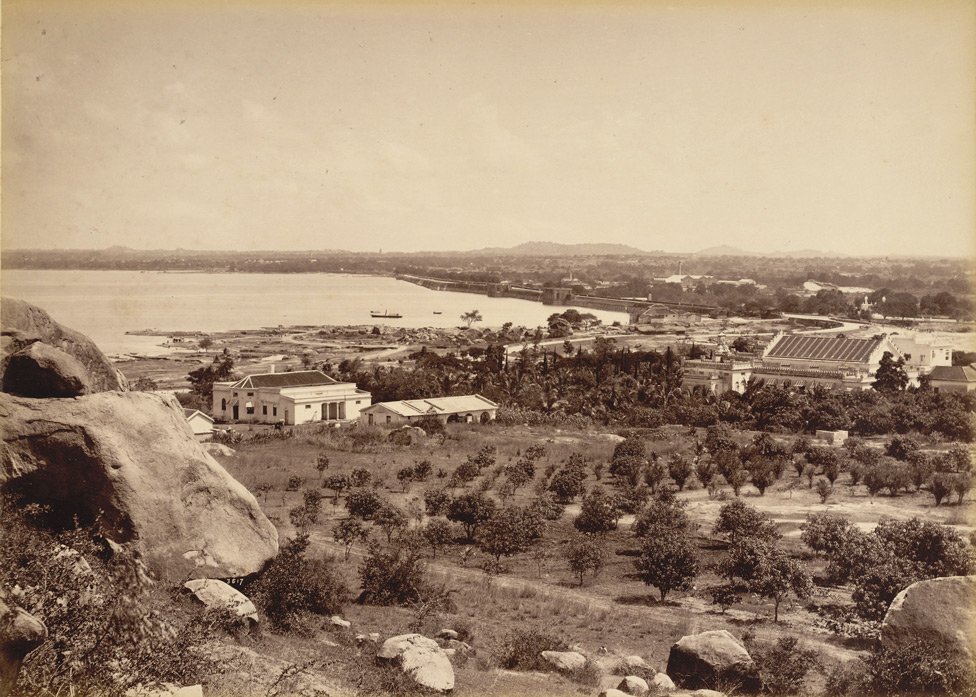

Edward Strachey wrote that these cantonments were vast tent cities which housed the now very substantial British military contingent that had arrived in the area following the two treaties James had signed with the Nizam. He talked of the cantonment as already extending near two miles and there being a considerable town formed

by the huts of the troops and camp followers. The situation is very high and airy commanding a fine view of the Hoosn Sagoor. Mountstuart Elphinstone added that the tent city was ‘very neat’.

The Subsidiary Force was substantial as the Company sent six battalions. It was commanded by Lieutenant Colonel James Dalrymple, but he died in January 1800, rather young at 43 years, in spite of best efforts by Dr Alexander Kennedy, the doctor of the Subsidiary Force. Nearly 5,000 British troops were housed in tents in the open areas of the maidan of the village Ulwul, north-east of Hussain Sagar. It encompassed an area of four square miles and in addition to 5,000 troops; there were several thousand civilian followers. After becoming the third Nizam of Hyderabad in 1803, one of the first actions of Sikandar Jah was to rename Ulwul as Secunderabad after himself. In autumn of 1804, James Kirkpatrick, the British Resident cheerfully reported the progress at Secunderabad to Sir John Kennaway, the previous British Resident at Hyderabad till 1794. The cantonments were already like a large regular town reckoned equal in extent to Cawnpore (today’s Kanpur).

The road from Hyderabad to the port city of Masulipatnam passed through Secunderabad. In 1805, it moved along the great rounded boulders of the Banjara hills, the rugged home of a gypsy tribe from distant Rajputana who left home to follow the fortunes of warring armies. Thereafter it followed the tent lines of the Subsidiary Force cantonments and snaked along the gleaming new obelisks and pyramids of the Parade Ground cemetery, where James Dalrymple was buried in one of the first graves of this cemetery. In 1806, Secunderabad formally came in being, after the order was signed by the Nizam allotting the land north of Hussain Sagar to set up the British Cantonment.

The Firangees in Deccan

James Kirkpatrick died in 1805, and was succeeded as British Resident by Thomas Sydenham till 1810. The Subsidiary Force started moving from tents to pucca buildings. Henry Russell took over as the Resident in Hyderabad in 1811, and continued till 1820. During his time as Resident, the relations between the East India Company and the Hyderabad durbar soured, as in a bid to impress his masters in Calcutta, Henry Russell imposed a series of damaging new treaties on the Nizam, forcing him to pay for ever larger and more unnecessary number of British troops at a total cost of forty lakh rupees a year – a sum which amounted to nearly half the entire tax revenue of Hyderabad. This vast fortune all went to pay the salaries of the enlarged Subsidiary Force and Russell’s new Hyderabad Contingent, for which the Nizam had no use and over which he had in reality little control. Meanwhile, flush with Nizam’s money, Secunderabad flourished into a cantonment town.

Till 1858, the cantonment consisted of barracks and huts extending to a distance of about five square kilometres with the artillery in front on the left flank and the infantry on the right. By 1860, the area had increased to 17 square miles and had a population, including the armed forces, to 50,000. Such cantonments were intrusions of unadulterated Englishness in the utterly Indian landscape and were increasing coming up across India as the Company deftly gained territory. The days of British ‘going native’ were passé, though James Kirkpatrick and the Resident’s Bodyguard were still staying in Hyderabad in the Residency on the northern banks of Musi river, in an old Qutb Shahi baradari pavilion within a walled pleasure garden. It is now the Osmania University College for Women (Koti). Later, the British Resident acquired a country house in Secunderabad where the shikar was aplenty. It was constructed in 1860. This Residency House is now known as the Rashtrapati Nilayam, the official retreat of the President of India.

The mutiny of 1857 left Deccan relatively untouched but the British anyway preferred to stay away – on spacious Mall roads, in exclusive clubs, living in huge bungalows (named so as the initial ones were built by Bengalis or Bangla) and praying in churches and chapels of the sprawling cantonments like Secunderabad. The locals in Hyderabad started referring Secunderabad as Lashkar meaning the army, as it was overwhelmingly an Army garrison with small hutments of Tirumalagiri, Bowenpally and Marredpally being the only earlier habitations.The bulk of the British forces and their commander were based in Bolarum, with the present Officers’ Mess of Bison Division being the erstwhile residence of the British commander of forces in Deccan.

The first Vicar Apostolic of Hyderabad was established in 1806 with residence at Secunderabad. An Anglican church came up in 1847 at Secunderabad. This Holy Trinity Church in Bolarum was in Gothic architectural style on land donated by the Nizam, and personally funded by Queen Victoria. At this time, Major General James Stuart Fraserwas the British Resident at Hyderabad. According to records available in the Holy Trinity Church, 21 British regiments were stationed at Secunderabad during 1847-1947 and were a part of the worship. The Church of St. John the Baptist was consecrated in 1813 at East Maredpally. It served the spiritual needs of the British Forces stationed at Lancer’s Line.

Union Jack over Bolarum As Bolarum

was the nerve-centre, the British decided to provide depth to the main garrison by providing an outpost which shall fight any hostile troops marching from Hyderabad to Secunderabad. In military parlance, it is called an advance position, and a British Infantry battalion was to be placed at this position. Soon after 1857, the construction of a seven meter high wall started at Trimulgherry, an anglicised name for Tirumalagiri, and completed in 1867. It was a mud fort with a circumference of about four square kilometres, called Trimulgherry Entrenchment and housed British troops. It had a moat all around, drawbridges across the trenches with arched entrance gates, towers and officers’ quarters. The four main gates were named after famous battles which the British had won in India. In an emergency, the entire European population could be accommodated within the Entrenchment. The Military Hospital Secunderabad is now housed here with a stone entrance gate and signs of a moat still existing. The road nearby is called Mudfort Road and another road in East Maredpally is still the Entrenchment Road. Afterwards, it was decided to place another but smaller outpost ahead of Tirumalagiri towards Hyderabad, in the feared direction of troubles. It was intended to delay rebels and providing early warning to the troops at Tirumalagiri rather than for prolonged combat. Thus, a picquet or picket was established which was manned by a small body of alert troops and able horses, lending this name to the picket area and road in Secunderabad. The rebels never came but the British remained keen to stay aloof from Hyderabad. Initially, only one road was constructed to connect the twin cities and it was called James Street. The James Street is now called Mahatma Gandhi (MG) Road, though the name James is retained in James Street Bus Stand, James Street Railway Station and the James Street Police Station.

Two deserving ‘James’ stand out from that era. Both were married to princesses from the Deccan nobility. Lieutenant Colonel James Dalrymple was the Commander of the Subsidiary Force and married to Mooti Begum, the daughter of Nawab of Masulipatam. He died in 1800, few years before Secunderabad actually came up. More likely, the James Road is named after Major James Achilles Kirkpatrick who was well known in Hyderabad as Hushmut Jung meaning ‘Glorious in Battle’. An ambitious soldier of the East India Company, he was wildly popular and thoroughly orientalised British Resident at the Court of Hyderabad, apart from being the husband of Khair un-Nissa, the ‘most excellent among women’. In 1936, to relieve congestion between Hyderabad and Secunderabad another road named King’s Way was constructed but only the British were allowed on this road. The King’s Way is now Rashtrapati Road.

Meanwhile, cantonment continued to grow and acquire new names and localities. Near Tirumalagiri, there existed a striking and huge crop of boulders. A gun was placed on top of it to ward off any advancing rebels and the area was called Gun Rock hill. Later the gun was deemed to be no longer required and a water tank was built there to supply water. Immediately after the treaty, as the East India Company did not have the required troops in Deccan, it requisitioned some troops from northern parts of India. Among them were tall burly Sikhs, giving the name of an area in Secunderabad as Sikhul Thota, now called the Sikh Village. However, many historians differ on this as the Sikhs were not recruited by the British until the fall of the Sikh empire in 1846 and the name may be therefore attributed to Nizam’s Sikh troops being settled here about a century ago. The second version appears likely, as corroborated by Count Edouard de Warren, a French soldier of fortune working for the Nizam, who confirmed the presence of Sikh, Afghan and Arab mercenaries in Nizam’s Army.

The Sekunderabad Flourishes

The town grew and the Secunderabad Railway Station was established in 1874. It was the main station of the Nizam’s Railway, a private company owned by the Nizams, and connected Hyderabad with the main line at Wadi Junction, of the Great Indian Peninsular Railway, a company owned by the British. While Secunderabad was coming up, large areas were left vacant by the British, with a view to enable the servants, gardeners, cooks, khansamas (male stewards), Bhishtis (water-carriers) and ayahs to live. Later these spaces were filled up with the present day civil settlements. In 1860, to honour the progress achieved by the British officers stationed at Secunderabad, the British government gave 10 acres of land for building a clock tower. A 120-feet high clock tower was constructed in 1896 and inaugurated by then British Resident Sir Trevor John Chichele Plowden on February 1, 1897 (whose daughter was meanwhile seeing Winston Churchill).

The Secunderabad Club was established on April 26, 1878 and was originally known as the Secunderabad Public Rooms. It was renamed the Secunderabad Garrison Club, the Secunderabad Gymkhana Club and the United Services Club. It became the Secunderabad Club in March 1903 and moved to its current location, an erstwhile hunting lodge gifted by Salar Jung I, the Prime Minister of Hyderabad State, to the British resident. It was located in the Tokatta village, which was Salar Jung’s personal jagir. The story goes that the Club was situated in a small run-down building and when the Resident desired to come to the Club, Salar Jung got to know of it and offered his hunting lodge as a fitting building to house the Club where the Resident could come in and spend his evening. The rules of the Secunderabad Club mention that the Salar Jung’s lineal descendants will be made members of Secunderabad Club without ballot or admission fee which is followed to this day.

Sir Winston Churchill, the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom during World War II, stayed in Bolarum in 1886 as a subaltern in the British Army. He visited the then Secunderabad Garrison Club and indulged in some peace-time soldiering. He moved to Bangalore in October 1896. Around this time he was generally broke, and ‘Lieutenant W. S. Churchill’ still owes the Bangalore Club thirteen rupees, as proudly displayed in the lounge of the Bangalore Club. Apparently, while no dues are balance at Secunderabad Club, Churchill’s connections to Secunderabad were romantic. His memoir, My Early Life, provides a vivid description of a polo tournament in Hyderabad won by Churchill’s regiment. Ramachandra Guha notes that it was here in Secunderabad that Churchill fell in love for the first time. The lady’s name was Pamela Plowden, and her father was a high official of the Indian Civil Service (ICS). She was, Winston wrote to his mother, ‘the most beautiful girl I have ever seen – Bar none’, and also ‘very clever’. However, the ICS father (also the Resident who inaugurated the Clock Tower in 1897) did not allow his daughter to enter into marriage with an impecunious army officer. Churchill returned to Bangalore, longed for action, and soon left for Nowshera to join the Malakand Field Force which was battling truculent tribes on the North-west Frontier.

In Hyderabad earlier Persian and since 1884 Urdu was the official language. But in Secunderabad it was English. Lallaguda, in one corner of Secunderabad became a ‘Little England’, as South Lallaguda had a sizeable population of Anglo-Indians, with most of them Catholics. Lallaguda initially was a fortified village constructed on orders of Thaniat un- Nissa Begum alias Bibi Sahaba, the favourite queen of Nizam Ali Khan, and the mother of Sikander Jah. Here a palace and a garden, near Moula Ali were constructed under the supervision of Lalla, one of the best architects of Hyderabad. Originally called Tahniat Nagar or Bibinagar, it came to be called Lallaguda after her death.

Being a British cantonment, Secunderabad was exempted from customs duty on imported goods thus making trade very profitable. New markets such as Regimental Bazaar and General Bazaar were created. Indians were allowed to shop only in Regimental Bazaar. A shaded avenue from Begumpet to Maredpally was called the Alexandra Road, primarily intended for the British, though Hyderabad nobility was welcomed due to their deep pockets. It divided the cantonment from its civilian appendage. Alexandra Road and Oxford Street had the most fashionable European shops.They included Badam Pyle (confectioners), Mapin and Webb (cutlery and crockery), Richard & Co. (goldsmith), Spenser (aerated drinks), John Pile (general stores) and Bright & Co. (chemists). John Burton was reputedly the most fashionable draper and tailor. The second son of Nizam VII, Prince Muazzam Jah had his sherwanis stitched at Burton’s. When he was there, no one was allowed entry, except European women. He would also buy the whole roll of cloth so that no one else would have a similar sherwani.

The Freedom post Midnight

By mid of 20th century, Indian independence was on the horizon. But Hyderabad still remained out of bounds for the soldiery of Secunderabad. The city therefore had to provide all amenities for a diverse citizenry. In 1945, the British restored an area of 5.6 square kilometres south of Alexandra Road with a population of about 100,000 to the Nizam, called the rendition of Secunderabad to the Nizam by the Resident. At that time, according to Narendra Luther, the author of Hyderabad: A Biography; before the rendition, a meeting was held between the Sub Area Commander of Secunderabad and high officials of Hyderabad on April 5,1945. It was agreed therein that in the transferred area, ‘high standards of services and cleanliness’ would be maintained. It was also agreed that the Percy’s, Montgomery and Whitehall hotels would remain open to visiting army officers for accommodation, concerts and parties. The closing time for bars in Secunderabad, 9.30 pm, would be maintained. The quaint cantonment was endeavouring to retain its unique character of a cosmopolitan and broadminded colonial town, which in many ways it has.

Hyderabad state joined the Indian Union in September 1948 after a military action codenamed Operation Polo, apparently because the Hyderabad city had number of polo grounds and race courses. Operation Polo resulted in some unintended consequences on the social pecking order of Secunderabad. The President of Secunderabad Club was Major General Syed Ahmed El Edross, an Egyptian and the commander-in-chief of the Hyderabad State army. Post Operation Polo, the officer who led the Indian attack from Solapur, Major General Jayanto Nath Chaudhuri (later the Army Chief ) became the next president of the Club, replacing Major General El Edross.

Secunderabad still remains a charming and liberal cantonment. The year 2006 marked two centuries since the birth of Secunderabad from 1806 when the order to grant land for the cantonment was formally signed by the Nizam. The old 1897 Clock Tower was chosen as the logo for these bicentenary celebrations. A decade hence, the year 2016 marks the golden jubilee of the Bison Division, the only fighting formation in the Deccan, which calls Secunderabad its home and the rich history of the place as its cherished inheritance. Its logo, so to say, is the indomitable Bison, and the motto is ‘Bash on Regardless’. The clock never stops ticking and the Bison never rests. The histories of Secunderabad and the Bison Division are inseparable, and perhaps everlasting.

An alumnus of RIMC and the NDA, Col Shailender Arya was commissioned in 44 Medium Regiment in December 1998, which he is now commanding since December 2013. He has served as GSO 2 of a mountain artillery brigade, a company commander with Assam Rifles in Nagaland, Staff Officer with the United Nations in Sudan and a GSO 1 (Operations) of a newly raised AR Sector HQ in a counter-insurgency environment in South Manipur. A four time USI essay competition winner, he contributes regularly to various defence journals and magazines.