Porus and Alexander, the two names are usually taken together. Alexander ascended the throne of Macedon when his father King Philip was assassinated in 336 BCE. He was just 20 years old. During the course of the next 13 years, till his death at an early age of 33 years, he was to change the course of world history and be given the epithet ‘Alexander the Great’.

The Kingdom of Macedon which Alexander inherited lay between the Ionian Sea to the West and the Aegean Sea to the East. If interposed on the present map of the world, this area would encompass roughly the Northern half of Greece. North of Macedon was Thrace, which was a dependency of Macedon and stretched from present day Istanbul to Bulgaria, Macedonia and Albania. To the South, which is the Southern half of modern day Greece, lay Thessaly and the League of Corinth.

Here too, the King of Macedon exercised hegemony. The great Persian empire lay to the East—a huge expense of area enclosed by the Eastern shores of the Mediterranean Sea, the Southern shores of the Black Sea and the Northern shores of the Arabian Sea,—thereafter, stretching Eastwards upto the Indus River. For Alexander, the Persian empire symbolised the ultimate conquest, for that was considered to be the end of the world, leaving no further worlds to conquer. And that was the aim he set for himself.

Conquest, to Alexander, was a fulfilment of what he believed to be his destiny. His thirst for conquest was insatiable. And he was a leader par excellence, for his men were wiling to follow him anywhere. Extremely difficult terrain or the most inclement of weather conditions did not deter his men from following him. Indeed, they would have followed him to the very gates of hell, had he demanded that of his men. He had inherited a lethal war machine from his father and had himself been taught by the leading teachers of his time. That, combined with his charisma and ambition made him take on the might of the Persian empire.

On assuming the throne, Alexander first quelled rebellion within his kingdom and then turned his gaze Eastwards towards the Persian empire. Beginning in 334 BCE, Alexander’s conquests included Anatolia, Syria, Phoenicia, Judea, Gaza, Egypt, Mesopotamia, Persia and Bactria. With the defeat of Darius III, Alexander’s empire reached the boundaries of India. Bessus, who was a prominent Persian satrap of Bactria, and who had proclaimed himself King after the defeat of the Persian army under Darius III, was killed in 329 BCE, thus removing the last vestiges of Persian rule, leaving Alexander free to turn his gaze towards India.

Alexander crossed the Hindu Kush Mountain range sometime towards the end of 327 BCE and probably crossed the Khyber Pass to begin his operations against India. He invited the chieftains of the former satrapy of Gandhara to submit to his authority. Some did. The rest he quelled by force. At places he faced stiff resistance, but soon, all the tribal chieftains were subdued, giving him control over the former Achaemenid satrapy of Gandhara. Alexander then moved to Taxila, which was ruled by King Ambi.

The king had made peace with Alexander by submitting to his authority. He also wanted the help of Alexander to subdue his rivals, King Porus and King Abisares. Alexander did not have to fight Abisares because the King sent his ambassadors and willingly submitted to Alexander. But King Porus refused to surrender tamely and readied his army for war. He was the ruler of Paurava, a small kingdom, lying between the Jhelum and Chenab rivers. He decided to fight Alexander on the Jhelum.

The Battle between Alexander and Porus

The army of Porus consisted of horse drawn chariots, cavalry, elephants and infantry. The chariots were pulled by two horses and had a driver and a soldier. Every chariot was fitted with long knives on the wheels. The larger chariots were pulled by four horses and were used to ferry troops. Each such chariot could carry six to eight men. The soldiers were armed with javelins and with bows and arrows.

The cavalryman was armed with lances and swords. The elephants were a strong component of the force, the huge beast being used to trample the opposition, while the soldier mounted on the elephant had his sword, lance and bows and arrows. The infantry component of the army of Porus was its weakest link. The soldiers were not equipped uniformly, their swords were heavy as were their bows.

In contrast, Alexander had an army of hardened soldiers and during the course of his conquests, more mercenaries had joined him. Alexanders army was well disciplined and organised and was superior to the army of Porus. In the autumn of 326 BCE, the two armies faced each other on the opposite banks of the Jhelum River. There are varying accounts of the size of the two opposing forces.

By some accounts, the army of Porus consisted of 20,000 infantry, 2000 cavalry, 1000 chariots and 200 war elephants. Alexanders invading force had 34,000 infantry and 7000 cavalry. While Alexander had the bigger and better trained army, they were fearful of the war elephants of Porus. Some element of battle fatigue had also set in, for the resistance offered by the local rulers, during Alexanders march from Bactria to India had been fierce. And feisty Porus, despite his smaller army, would not be a walkover for the mighty army of Alexander. And thus the two armies faced each other, separated by the Jhelum which at that time was in spate.

The heroism of Porus became legend and was acknowledged by Alexander himself. When Porus got down from his elephant to meet Alexander, the latter asked him, “How do you wish to be treated?” And Porus’s famous reply, “Like a King,” so impressed Alexander that he restored to Porus his kingdom.

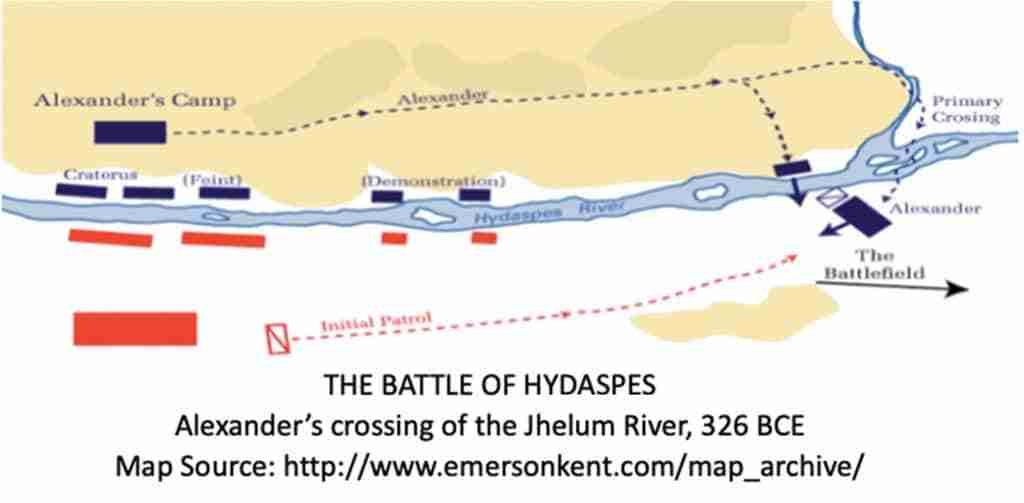

King Porus had placed his chariots in front, facing the Macedonian army and behind the chariots, he placed his elephants, spaced at intervals of 15 meters. The infantry was behind the elephants and the cavalry was placed to cover the flanks. As a stratagem, Alexander had camped his army in a manner that was visible to Porus. Every evening, his troops would go to the riverfront and make a show of readying to cross the river. The troops of Porus would get ready for battle, but Alexander never crossed and his troops would return to their camp.

After many days, thee troops of Porus refused to respond to the provocation. Alexander finally crossed the Jhelum about 27 kilometres upstream, making use of a thunderstorm to achieve surprise. He had prepared rafts to transport the troops and horses across the river. Porus did not realise that Alexander had crossed with the major component of his force and force and thinking this to be a smaller force, he sent a force of 100 chariots and 4000 cavalry under the command of his son to confront them.

The battle here was fought fiercely and Alexander’s horse Bucephalus was killed. King Porus now had to face Alexander from two sides and was thus caught in a pincer. The battle that ensued was fierce and bitter, with heavy losses on both sides. Finally, Alexander prevailed, but as recorded by Plutarch, the Greek historian, “The combat with Porus took the edge off the Macedonians’ courage, and stayed their further progress into India”. If this was the resistance offered by a minor King, to the great Alexander himself, then what of the more powerful armies which lay further ahead.

Alexander would have had to confront the mighty kingdom of Magadh, ruled by the Nanda’s, whose army was many times the size of the forces of Alexander. And so Alexander called a halt to his campaign, to the great jubilation of his soldiers. The great invader had finally been stopped in his tracks.

The heroism of Porus became legend and was acknowledged by Alexander himself. When Porus got down from his elephant to meet Alexander, the latter asked him, “How do you wish to be treated?” And Porus’s famous reply, “Like a King,” so impressed Alexander that he restored to Porus his kingdom.

A tactical loss, but a great strategic victory

History records that the battle of Hydaspes, as it came to be known, was won by Alexander. At the tactical level, this may be true, but the larger outcome of the battle gives a different perspective.

Alexander’s ambition to conquer the world was as insatiable and strong as ever. And to reach the end of the world, he had to conquer territories in the East and reach the Ganges River and thereafter follow its course till it flowed into the Ocean in the East. But in between lay the Kingdom of the mighty Nandas and after seeing the resistance put up by Porus, Alexander’s army could not be cajoled into proceeding for further conquests. They simply wanted to return home. And so Alexander was forced to abandon his plans for further conquest.

The attempted conquest of India could not take place, because of the heroic resistance offered by King Porus, which severely dented the morale of Alexander’s army.

The return journey was not taken on the route they had come for conquest. That would have looked like a retreat. So Alexander withdrew westwards, but faced resistance from local tribes and was severely wounded in one such skirmish, but he survived that battle and his wounds healed. He finally reaching the Makran coast after a perilous journey through the desert which had cost him the loss of about 70 per cent of his force. He then moved on to Persia and in 323 BCE arrived in Babylon. Here he took ill and died at the young age of 33 years.

The attempted conquest of India could not take place, because of the heroic resistance offered by King Porus, which severely dented the morale of Alexander’s army. Porus had thus won a great strategic victory, having finally stopped the mighty Alexander.