Introduction

PEOPLE’S LIBERATION ARMY AIR FORCE (PLAAF) VS. INDIAN AIR FORCE (IAF)

The Sino-Indian border issue is one of the biggest hindrances to the normalisation of ties between the two Asian giants. While many wonders whether Asia is large enough for them, and their growing ambitions, India’s strategic community focuses on more immediate and pressing questions. Without losing sight of the overall trajectory of Sino- Indian relations, they also have to consider, as military planners do, the possibility of China initiating a fresh military conflict in the near or mid-term in support of its territorial claims. This brief analysis looks at the role of airpower in a potential conflict between India and China with a comparative qualitative and quantitative study of both air forces and their relative capabilities in the Tibetan region.

The Lessons of 1962 Sino-Indian Conflict

The 1962 India-China war has understandably left a lasting bitterness on the bilateral relations between the two countries. On the Indian side, one of the enduring controversies of this war has been the non-use of the combat arm of the Indian Air force, which is commonly believed to be a major cause for the debacle. In the 1962 war, China was hardly in a position to use its air power to influence the ground battle. It is well known that in 1962, China’s offensive air capabilities in the Tibetan region were practically non-existent because of the design/operational limitations of its fighter fleets, which consisted mainly of MiG-15s, MiG-17s and a few MiG-19s and because China possessed hardly any worthwhile high-altitude airstrips in Tibet for these aircraft to operate from. Similarly, China’s capability to strike Indian cities with its bomber aircraft such as the IL-28s was also limited owing to constraints of range when operating from its mainland airfields. The Chinese bombers would have also been highly vulnerable to interception by the IAF air defence fighters once over Indian Territory.

The Indian Air force, on the other hand, could operate its combat aircraft with ease from its many airfields located in the plains in both the western and eastern theatres without compromising on their payload capabilities and these could be employed in traditional interdiction and close air support roles. Properly used, Indian jet fighters would have caused havoc to the (deprived of air cover) Chinese ground forces. In the end however, neither China (because it could not) nor India (because it would not, largely due to unfounded fears of the Chinese Air Force) used their combat aircraft, resulting in the Indian army succumbing to the much superior Chinese ground forces. But that was more than half a century ago. In the present scenario, it can be said without any ambiguity that in the event of China initiating another round of conflict in the form of a limited war to militarily settle the border dispute with India, it can and would make full use of its air power in a bid to force the outcome in its favour once again.

The question that looms large then is – in the current scenario, how does PLAAF match up against the Indian Air force? And what are their respective capabilities and constraints in case of another conflict erupting in the Himalayas?

PLAAF: Modernised and Transformed

A well-planned, long-term and timebound approach to military modernisation – conceived as part of Deng Xiaoping’s ‘Four Modernisations’ – was instrumental to start the process of transforming the PLAAF from an antiquated, derelict, poorly trained and over-sized force of the 1960/70s to a modern ‘lean and mean’ aerospace power with increasing proficiency to undertake its stated mission in the 21st century. It was not an easy task to start the process of the PLAAF’s modernisation, which was so heavily shackled to the archaic system of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA).

It is sometimes said that one of the reasons China went to war with Vietnam was Chairman Deng Xiaoping’s desire for his army brass to understand the importance of air power even at the expense of Chinese forces getting a bloodied nose in Vietnam. However, the real eye-opener for the Chinese leadership was the US ‘shock and awe’ aerial assault against Iraq during the 1991 Gulf war, which established beyond doubt the predominant role played by air power in the conduct of modern warfare. American mastery over the air and its technological superiority spurred transformation efforts in the PLAAF.

Adopting the philosophy of ‘buy/steal and make/reverse-engineer,’ China’s military modernisation (especially of the PLAAF) has been progressing purposefully over the last two and a half decades. China made full use of Russia’s post-cold war economic hardships by buying its military equipment and aerospace technologies on favourable terms. It bought the Su-27 aircraft from Russia and copied it to produce its indigenous version, J-11, in large quantities. It also equipped the PLAAF through outright purchase from Russia, the Su-30 MKK (an advanced version of Su-30) and the Su-30 MK2 air dominance fighters. The Israelis, on the other hand, passed on the technology connected with their stalled ‘Lavi’ programme for China to successfully develop and produce its 4th generation and 4th generation+ J-10 and J-10B jet fighters, respectively. But it is not only the Soviet/Russian designs or the Israeli aerospace technologies which provided the leap forward; the Chinese aerospace scientists themselves have been carving out big successes in indigenous design and development. On January 11, 2011, China stunned the global aviation community by test-flying the Chengdu J-20 – its first 5th generation stealth jet fighter. Not to be undone, Shenyang, China’s second manufacturer of jet fighters made it a double on October 31, 2012 by launching the J-31, another 5th generation jet fighter on its maiden flight. Both these prototype designs are reportedly under different stages of development and are likely to become operational around 2020.

Having discarded the so-called ‘deadwood’ from its inventory, the PLAAF currently has around 1,700 combat jet fighter aircraft comprising of a judicious mix of 4th/4th+ and 3rd generation aircraft

In addition, the PLAAF has a large inventory of transport aircraft: IL-76 strategic airlifters (20-30), multipurpose Y-8 transporters derived from the Russian four-engined An-12 design (100-120), Y-7 based on An-26 twin turbo-props and 300+ Y-5 singleengined light utility aircraft. The PLAAF also boasts of a sizeable number of VIP transport aircraft which include Tu- 154M and the smaller Bombardier Challenger 600, etc. In addition, it fields 500+ helicopters comprising of attack and utility versions of indigenous and Soviet designs. It has also acquired about two dozen Sikorsky S-70 Black Hawk utility helicopters from the US.

The PLAAF’s ‘force-multiplier’ fleet of Airborne Warning and Control System (AWACS), Airborne Early Warning and Control (AEW&C) and Flight Refuelling Aircraft (FRA), though small, is likely to grow with time. However, where China really scores is on its holdings of a very large variety and numbers of Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV)/Unmanned Combat Air Vehicle (UCAV) and target drones which could be used for multifarious missions. Also, China possesses large quantities of short/medium range ballistic and cruise missiles which could be used to strike all types of targets inside enemy territory with conventional warheads.

IAF (Indian Air Force): Still in the Pits – Present and Future

Ironically, in the 1990s, when China hit the ‘fast forward’ for the PLAAF’s modernisation, the Indian Air force was confronted with a void due to India’s then precarious financial position and breakup of the Soviet Union – till then, the major provider of defence equipment to India. This had a ripple effect on the Indian Air force, which began to experience crippling draw down in terms of the strength of its combat jet fighter squadrons and other combat equipment. The Indian Air force, which had laboriously built up its combat force levels to 39 ½ fighter squadrons by late 1980s, lost almost a quarter of its strength and was teetering at a record low of around 29 squadrons by the middle of the last decade. This happened despite the induction of Su- 30 (later Su-30 MKI) into the IAF which had commenced around the turn of the last century. The extraordinary delay in the indigenous LCA (Tejas) programme did little to help matters. In an endeavour to stem the downslide, the Indian Air force ordered more Su-30 MKIs—with the order swelling up to 272 aircraft – and vigorously pursued the 126-aircraft Medium Multi-Role Combat Aircraft(MMRCA) programme. However, while Indian Air force has successfully inducted close to 200 Su-30 MKIs into service its MMRCA programme ran into all kinds of troubles after Dassault won the competition with its Rafale offer on January 31, 2013. The impasse was finally broken by some out-of-the-box thinking on the part of the PMO with Prime Minister Narendra Modi deciding to go in for the outright purchase of 36 Rafale jet fighters from France in an unprecedented Government-to-Government (G2G) deal. While this move may hasten induction of the aircraft into service, the drastic reduction in numbers, unless remedied, is bound to create an adverse impact on the operational preparedness of the IAF. It may also be remembered that purely in numerical terms, the Indian Air force has slid down to just about 700 aircraft, from its earlier holdings of more than 900 jet fighters.

In the coming years, the biggest worry for the Indian Air force would be to somehow hold on to its present strength by matching phased retirement of the older MiG-21/MiG-27 variants with new inductions arising out of the ongoing programmes. These would include 70 more Su-30 MKIs by 2017-18, license-produced by HAL at the rate of 20 per annum.

The first couple of indigenous LCA (Tejas) aircraft have been delivered to the Indian Air force for operational evaluation with the FOC (Full Operational Clearance) slated for end 2015. It is hoped that HAL will set up full-scale production of the Tejas MK I and later MK II version and start delivering these aircraft to the Indian Air force in real earnest. In addition, it is hoped that the Rafale (winner of the MMRCA competition) contract for outright purchase of 36 aircraft will be inked soon and additional Rafales acquired at a later date to equip at least three Rafale squadrons to ensure operational viability. However, it is obvious that these measures alone would not be sufficient to keep the Indian Air force on track to get to a figure of 42 jet fighter squadrons, by the end of India’s 13th Plan Period i.e. by 2022, as envisaged by Mr AK Antony, – defence minister during the previous UPA government. The new defence minister, Mr Manohar Parrikar of NDA government has hinted on more than one occasion for some out-of-the-box thinking for acquiring the necessary numbers such as making in India another single-engine fighter which would be more capable than the indigenous LCA by shifting the foreign vendor’s entire assembly line to India. It is now known that Saab from Sweden has offered to make its Gripen NG advanced fighters in India which would not only equip the Indian Air force but could also be exported to friendly countries by India. Eventually, India would need about 1,000 jet fighters to be able to effectively meet the future challenges to its security.

PLAAF vs. IAF: Commonalties and Differences

Both the PLAAF and the Indian Air force have undergone substantial changes in their doctrinal concepts in the last couple of decades. The defining moment for the Chinese armed forces (including PLAAF) came with the articulation in 2004 by President Hu Jintao of “historical missions of the armed forces for the new stage in the new century,” which was codified in the Chinese Communist Party Constitution in 2007.

The new guidelines require the Chinese armed forces to secure China’s strategic interests even outside its national territorial boundaries. ‘Active defence’ is the operational concept of China’s national strategic guidelines for the new period. The PLAAF would have a leading role in China’s active defence strategy. China’s operational strategy is based on long-range strike and anti-access and area denial (A2AD) capabilities which is not specific to its maritime domain and could be brought to bear over its land borders as well, with obvious implications for India.

The Indian Air force has also gone through metamorphic changes in its doctrinal concepts in conformity with the increasing requirements of a resurgent India. It is not coincidental that both the PLAAF and the IAF are converging on their respective goals of transforming themselves into modern strategic air forces with continental reach and allweather precision strike capabilities and the ability to conduct air operations in highly information-intensive and network-centric scenarios.

While the doctrinal concepts of the two air forces may be on converging trajectories, where the PLAAF scores over the Indian Air force is in terms of quantitative superiority. As brought out earlier, the PLAAF already has modern fighter fleets with close to 1,700 such aircraft on its strength. They are already twice as much as what the Indian Air force hopes to achieve in the next 10 years. In addition, China is developing J-20 and J-31, two distinctively designed 5th generation aircraft. Fortunately, India has joined up with Russia to co-develop the PAK-FA 5th generation fighter aircraft which may become available to the Indian Air force at a time, coinciding with the indigenous Chinese 5th generation fighter inductions into the PLAAF. However, due to great disparity between the ‘defence budgets’ of the two countries (in 2012: China’s $106 billion – which could exceed $200 billion with hidden defence expenditure – vs. India’s $40 billion), quantitative differences would continue to remain in China’s favour.

The second aspect of the PLAAF’s superiority over the Indian Air force lies in its ground-based air defence systems. China’s sizeable holdings of SAM systems such as the Russian-supplied S- 300 PMU series and indigenous HQ- 9/HQ-12 with engagement ranges varying from 50-150 km clearly overshadow the Indian Air force present capabilities even while the latter is trying to catch up with its newly inducted indigenous Akash and the Israeli Spyder SAMs and joint development with Israel of a 70kmrange MR-SAM system.

The third area of PLAAF’s superiority over the Indian Air force lies in the realm of ‘unmanned’ UAV/UCAV and drone systems. China has been innovative in converting more than 200 of its J-6 (MiG-19) aircraft into unmanned drone systems with a variety of roles ranging from ISR to bombing of enemy ground targets. In addition, China also has a large arsenal of short/medium-range ballistic and cruise missiles which could be used against enemy targets in varying depths in enemy territory.

Despite these advantages the larger questions are: In case of a Sino-Indian conflict, how would the Indian Air force fare against the PLAAF? And will China be able to attain air superiority over the Tibetan plateau?

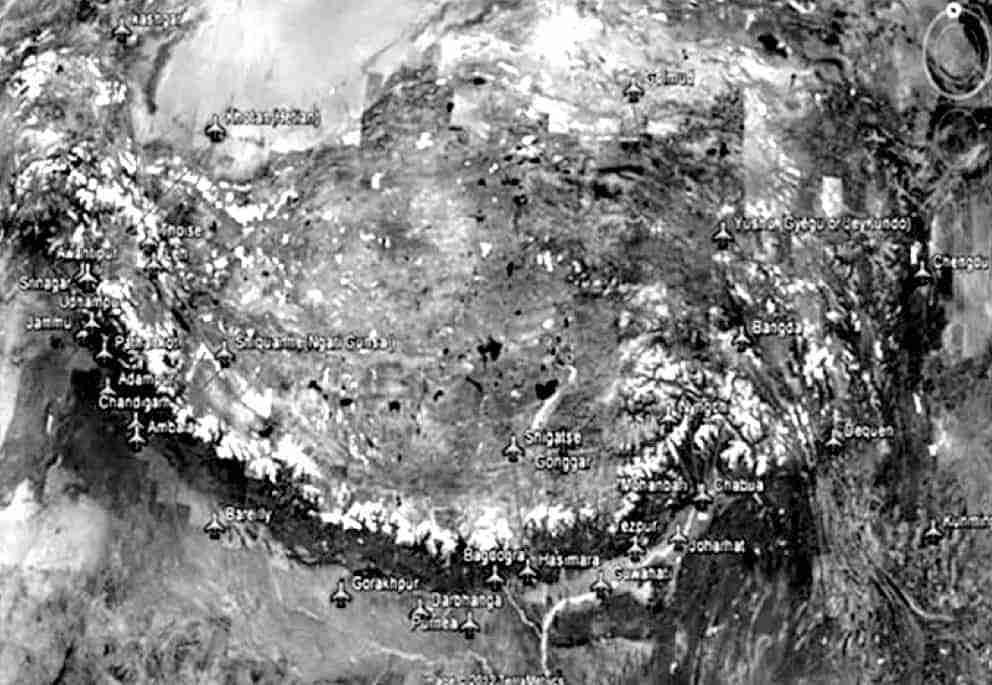

PLAAF in Tibet: Limited Capabilities No one can deny the tremendous efforts made by China to create unprecedented infrastructural capabilities in the Tibet Autonomous Region (TAR). An almost trillion dollarendeavour has not only resulted in the building of more than 58,000 km of world-class roads and highways, but also in creating the world’s highest rail link connecting Tibet’s Capital Lhasa to Golmud and through it, to the rest of China. In the aviation sector too, China appears to have made great strides by developing a number of airfields through the length and breadth of Tibet, the latest at Nyingchi, merely 30 km away from the Arunachal Pradesh border. China can boast of a full-fledged international airport at Lhasa, complete with what may be termed as the highest aerobridge in the world. Xigatse, in the southern portion of Central Tibet is another well-developed airfield. However, a Google-eye scrutiny of the airfields in the TAR would reveal that while adequate runway lengths have been provided to compensate for the ‘altitude factor’, most airfields have only rudimentary support infrastructure which would make it difficult for the PLAAF to carry out large-scale air operations in a sustained manner in Tibet. The PLAAF aircraft would also be handicapped in terms of payload capabilities while operating from highaltitude airfields in Tibet. Also, PLAAF does not have adequate flight-refuelling capabilities, allowing only limited number of aircraft to get airborne with full payload but partial fuel and then refuel in the air to reach distant assigned targets.

On the other hand, the Indian Air force would have access to a greater number of airfields, with much better support facilities which it could use for air operations with full payloads against targets in the TAR. In other words, even though the PLAAF may be more than double the size of the Indian Air force in terms of its overall combat aircraft strength, in a border war with India, it may find itself at a disadvantage vis-à-vis the numbers (and reduced payloads), it can field against the Indian Air force. Also, without adequate number of ‘blast pens’ (protective aircraft shelters) the PLAAF aircraft would be vulnerable to counter-air strikes by the Indian Air force.

IAF has the Edge

If China does decide to teach India another ‘lesson’ in Tibet, it would bank heavily on its tremendous infrastructure to mobilise massive ground forces (between 30 to 40 divisions) and support elements to overwhelm Indian defences. Due to inadequate ground infrastructure on its side, the Indian army would also have to bank heavily on the ‘air’ for maintenance and logistic support. Both the PLAAF and the Indian Air force, having already achieved a certain level of modernisation (although in differing degrees) would try to achieve air dominance/air superiority by conducting DEAD/SEAD (Destruction/ Suppression of Enemy Air Defences) and counter-air operations against each other.

The PLA could resort to the use of its superior tactical ballistic/cruise missiles and unmanned drones with conventional warheads in these missions to offset the shortcomings of its air force.

However, missiles are handicapped because of their having only a single-shot capability. Therefore, if the Indian Air force improves on its already existing facilities to ensure proper active/passive AD and rehabilitation capabilities at its airfields and radar sites, it could well weather the Chinese onslaught. On the other hand, it could use this very shortcoming of the PLAAF to its advantage to achieve air superiority/favourable air situation in the battle zone.

Once this is achieved, the Indian Air force could not only remove the danger of PLAAF interfering with ground operations, but also provide much needed close air support to the Indian army to help it ward off numerically much stronger Chinese ground forces. In this scenario, even a stalemate without loss of territory on either side would be tantamount to a strategic victory for India.

In his IAF career spanning more than 40 years, Air Marshal VK ‘Jimmy’ Bhatia had the rare distinction of being the AOC-in-C of three operational commands, i.e. Central, South-Western and Western Air Command in succession. He was awarded Vir Chakra gallantry awards in both Indo-Pak wars of 1965 and 1971. He is also the recipient of the PVSM and AVSM Presidential awards. Apart from pursuing professional interests in the field of non-conventional energy sources since his superannuation, he is also engaged actively as a writer and analyst on matters connected with military and civil aviation and international relations. He has been a member of the Executive Council of the USI for six years and presently is the Managing Editor of the India Strategic Group.