MARATHA NAVAL PRIDE – In 1534, Nano da Cunha must have viewed the Treaty of Bassein with a tremendous sense of satisfaction. It would take a year more to consolidate on the gains, but the infighting between the native emperors and their current lack of interest in the sea had played right into his hands! With a crusader’s zeal, armed with a sword in one hand, cross in another, emboldened by the Papal Bull – ‘Terra Nullius’– his predecessors had firmly rooted Portuguese influence throughout the Konkan coast. Chaul was occupied by a victory against the Malmuks in 1507, Dhabol succumbed a year later. Goa was subjugated, lost and re-conquered by 1510 and this treaty with Sultan Bahadur Shah gave the Portuguese permission to build a factory in Diu, control of all the islands of ‘Bombaim’ upto Bassein and permission to levy duties and tolls on all sea trade from these ports. He must have felt it intuitively, as he sailed the largest fleet under sail through Bombaim, while his forces laid waste to Thane and Sopara, that this would be the epicenter of Portuguese control of the Arabian sea.

This coast and its sea lanes would need protection. This strategic vision had already begun manifesting with fortifications of Arnala and Chaul by 1531. Diu and Bassein were fortified in 1535, Bombay in 1554, Goa in 1613 and the strategic Bandra fort overlooking the Mahim bay was completed by 1640. Fortification of Madh island culminated the consolidation of Portuguese maritime ambitions.

In terms of maritime history, the significance of this event is best understood, only in retrospect. While the Portuguese influence was strong in the west coast of the sub-continent, Indian sovereigns with maritime influence and the maritime interest by itself had declined to naught. The Maurya, Chola, Kalinga and Vijayanagar empires had risen and fallen. After the battle of Swally in 1612, the English East India Company had also emerged as a discernible power centre, dominating both the Northern coasts and the Sultanate at Delhi.

Aurangzeb, having inherited Timur’s legacy and an empty treasury, was desperately trying to keep his empire together, ironically by a continental expansionist policy, probing deeper into the peninsula. The endowment of Bombay to Britain, as part of Princess Cathrine’s dowry,by Portugal in 1661 progressively transformed these marshy pestilent swamps to British citadels. Realising the strategic importance of the Maharashtra coast, especially the natural harbour of Bombay – The British had fortified the Manor house in Mumbai and subsequently, fortification of strategic positions at Worli, Mazagaon, Sewree and Sion were completed by 1680.

While the Portuguese and the British were playing out their European ambitions in the Indian sub-continent and consolidating respective positions on the coast of Konkan, a son of the soil, a born soldier and visionary emerged. He engaged with the Mughals, the Europeans and their satraps with equal disdain and emerged victorious. With an iron will and gallantry to match, Shivaji, forged an empire out of the political mess of his times. One attribute of Shivaji, unique to his times, is his maritime strategic vision. A vision which was institutionalised into his empire building process to such an extent that the concept outlived the individual and was an essential aspect of Maratha national policy for generations to come. The effect of this legacy on continental as well as maritime history has been profound; rightfully earning him and his worthy successors the epithet ‘Chatrapati’, the Sovereign.

The key facets of Shivaji’s maritime efforts were encouraging indigenous ship building, manufacture of naval weaponry, ordnance, coastal and island fortifications, modern approach to Naval recruitment, training and administration. The first ships of the Maratha navy were launched a good 150 years after the arrival of the Portuguese. Bhiwandi, Kalyan and Panvel were the principal ship building centres. The Maratha Navy had different types of fighting ships- Gurabs, Galbats, Pals and Manjhuas. The land based tactics of guerilla warfare was extended at sea by the Angres. Maratha vessels were simple, light, of shallow draught, fast, maneuverable, potent and highly effective. While this restricted their role to coastal engagements, they satisfied his overall maritime vision which precluded high seas fleet engagements with the vastly superior Portuguese and British fleets. Records mention an assembly of 140 vessels at Nandagaon and by 1680, the Maratha Navy is said to have become a formidable force and had 45 large ships (300 tonnes), 150 small ships and over 1,100 Galbats (small boats).

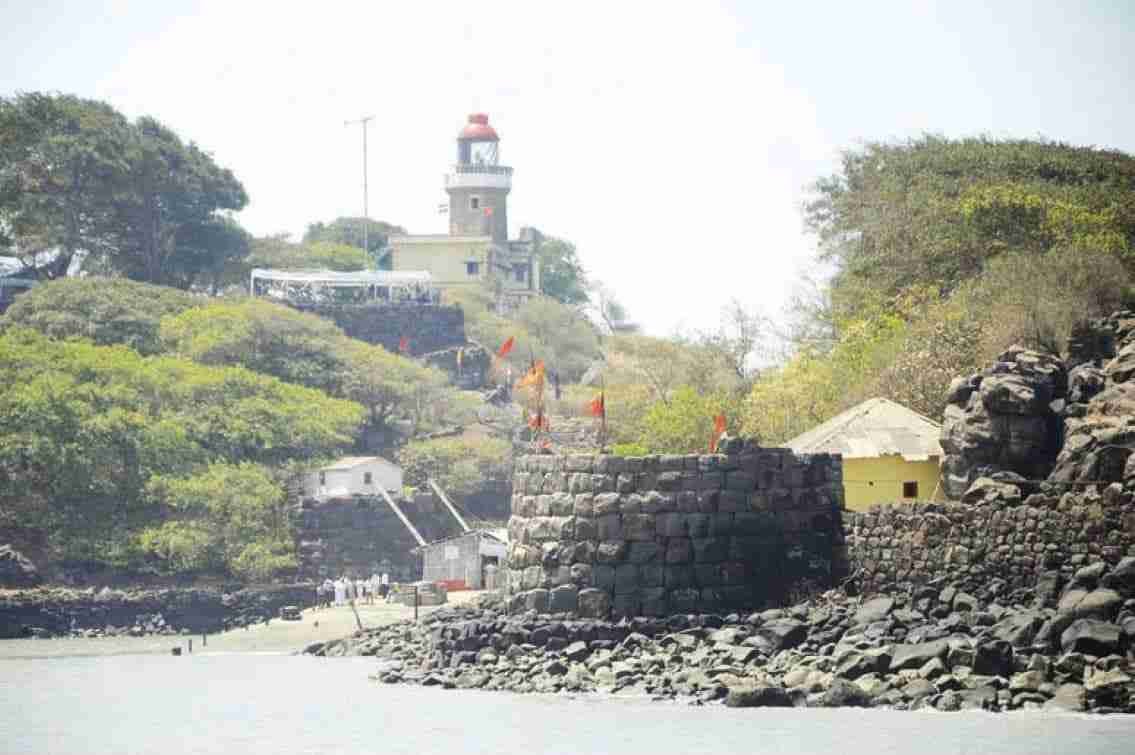

Marathas like their contemporaries, invested heavily in fortifications. They built some and strengthened others that they conquered. In Maharashtra, three types of sea and coastal forts are found in Mumbai, Thane, Raigad, Ratnagiri and Sindhudurg districts. The first being those referred to as Janjira in Marathi which means an ‘island’. Forts like Murud, Khanderi and Sindhudurg are some examples. The second type of forts are the coastal forts, built on a hill close to the coast. Vijaydurg, Kanakdurg, Devgad, Goa are among the coastal forts. The third type of forts were built on a hill near a creek, a little away from the seashore. Gopalgad, Purnagad and Ratnagiri forts fall into this category. These forts in many ways decided the regional maritime superiority.

The fort of Vijaydurg, famous for its amazingly built ‘invisible’ fortification, is an interesting example of ingenuity in this effort. Around 1720, Charles Boon, Governor of Bombay province, made several attacks on the fort with an enormous ship (much like a floating fortress) built in the Dabhol dockyard. It was towed as it was too heavy for its sails. The ship reached a certain point and then could move no more, despite a lot of effort. The Maratha Navy, was in the Vaghotan creek. Caught between their inability to physically proceed any further or even face the Maratha navy, they retreated. Centuries later, in 1991, a diving operation conducted by HQWNC and National Institute of Oceanography, revealed a 6-7 m wide wall built by piled up stones, parallel to the seaside fortification of Vijaydurg, 120 – 150 meters away from the fort, running to a length of 122 meters. The wall is 3 to 4 meters high and cannot be seen from above, nor is it visible at low tide. This wall stopped the English from reaching the fort.

The waning of the Maratha sea power was almost inevitable. When they were finally defeated in the Anglo-Maratha wars, all these fortifications came under the British and the British Naval supremacy in the region was absolute. This also resulted in consolidation of the regional security infrastructure that the British had started post acquiring Mumbai. The metamorphosis of the local flotilla from the Bombay Marine to the Royal Indian Marine to the Royal Indian Navy and finally the Indian Navy is a saga in itself.

Today the Maharashtra Area is placed under the jurisdiction of the Flag Officer Maharashtra Area and is mandated to ensure protection of this coast, the associated sea-lanes and the resource assets of the Offshore Development Area. Although the Maharashtra Naval Area has seen differing command and control through the ages, its importance to the overall significance to national security has never diminished. The vision and valour of the Marathas continue to inspire the dedicated and gallant personnel who oversee the coastal defence and seaward security of the Konkan coast.