If success in war and unmatched physical and moral courage are the yardsticks to measure the greatness of military commanders, then there can be no doubt that Lt Gen Sagat Singh takes the pride of place as India’s greatest battle field commander, deserving to be counted amongst the greatest military commanders in history of not only India but the world. It may be a coincidence or maybe providence that this year is not only the centennial of Gen Sagat Singh but also of Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rehman, the father of the Bangladesh nation, towards whose freedom General Sagat Singh contributed so much.

Sagat was born on 14 July 2019, and on this his centennial year, both the Indian and the Bangladesh Armies are holding commemorative functions to honour his memory. And the two countries have much to thank him for. If victory in the Liberation War was achieved in such a remarkably short time, the credit has to be mainly given to him. The capture of Dacca by our forces was neither planned nor factored in the operational orders of our Army Headquarters nor of Headquarters Eastern Command. In fact Lt Gen Aurora, GOC in C Eastern Command was vehement in opposing Sagat’s plans to move on to Dacca. But Sagat not only crossed the mighty Meghna which nobody thought was feasible but on the 9th day of the commencement of the war, on 12 December 1971, his leading troops with 4 Guards in the van had reached the suburbs of Dacca and on 14 December had occupied Gulshan Town, the poshest locality of Dacca where the Dacca Zero milestone was placed when orders were received to halt further advance as the Pakistan Army had agreed for a ceasefire which became effective on 15 Dec 1971.

If his role in the 1971 War was his only achievement he would still be considered as one of the greatest battlefield commanders. But Sagat had much more on his plate of achievements than the sterling role he played in contributing to that victory. In September 1961, he was promoted to the rank of brigadier and posted as the brigade commander of India’s only parachute brigade, the 50th Parachute Brigade. During the Goa operations in 1961, the Parachute Brigade under his command was the first to enter Panjim, the capital of Goa. So furious was Salazaar, the dictator of Portugal that he put a prize of 10,000 US Dollars on his head! In 1962, the Parachute Brigade was placed on twenty-four hours notice for deployment but by then the Chinese had halted their advance and the Brigade did not see any action.

On promotion to Major General, he commanded a Division in the eastern sector and was responsible for the Nathu La sector in Sikkim. In 1966 and 1967 he neutralised all Chinese attempts at incursions into Sikkim and thanks to him Nathu La Pass is still in our hands today. Orders had been issued by XXXIII Corps and Eastern Command to vacate the posts, but Sagat chose to ignore them and in the event, the Chinese forces backed off, with Nathu La remaining in Indian territory.

After successful command of a Division, he was placed in command of 101 Communication Zone, where he played a pivotal role in tackling counter-insurgency operations in Mizoram. The insurgency in Mizoram had started on 28 February 1966 with armed attacks on the posts of 1 Assam Rifles in Aizawl and Lunglei in a planned uprising called Operation Jericho. On 1 March 1966, Mr Laldenga made a call for independence and exhorted all Mizos to join the revolt. The uprising was put down by the Indian Army under the dynamic leadership of General Sagat Singh. The pressure he thereafter exerted on the insurgents enabled the Central Government in August 1968, to offer an amnesty to the insurgents, which resulted in the surrender of 1524 insurgents. In 1969, when he found that the Mizo hostiles had been given refuge in East Pakistan, he sent a battalion sized force across the border into East Pakistan, thus sending a very clear message that the insurgents would have no shelter, even in a neighbouring country.

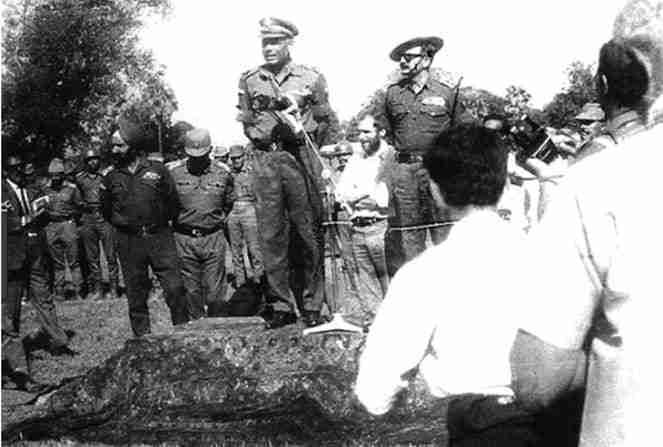

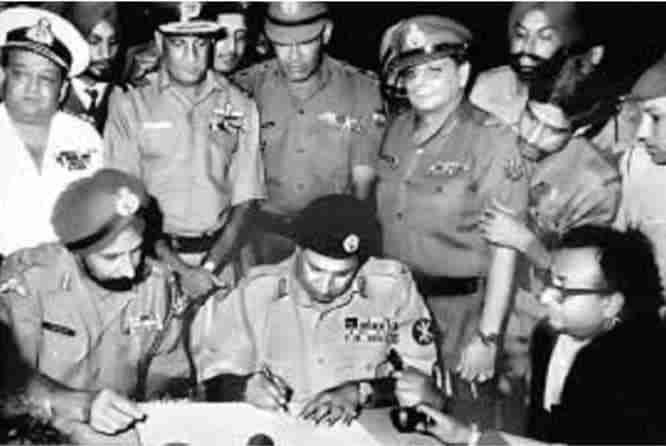

Firm action and more amnesty offers brought back the people into the mainstream and a few years later led to a stable political solution. Mizoram remains the most successfully concluded anti-insurgency operation in our history. An unrecorded but very important fact is that the people of Mizoram, in spite of whatever feelings they may have had for the civil administration, treated the Indian Army with respect and even love. At the height of the insurgency we could move around unarmed and receive smiles and friendly greetings from the locals. For his distinguished services, the General Officer was awarded the Param Vishisht Seva Medal. In December 1970, he took over the command of HQ IV Corps as a lieutenant general. The corps made the famous advance to Dacca over the River Meghna during Bangladesh Liberation War in 1971 and on 16 December, Sagat was standing behind General JS Aurora, the Eastern Army Commander and Gen Niazi of the Pakistan Army, when the latter signed the instrument of surrender.

What was it that made Gen Sagat so successful in battle? Simply put, it was his focus on the mission to the exclusion of everything else. This is best told in the words of Group Captain Chandan Singh (later AVM).

On the evening of 5 December, General Sagat Singh spoke to me over the phone and told me to meet Maj Gen KV Krishna Rao, GOC 8 Mountain Division, the next day and inquire if I could be of help in his operations. Next day, I flew in a helicopter to Shamshernagar airfield to meet the GOC. The airfield had been badly cratered by our shelling, but I managed to land the chopper. Then I commandeered a jeep and went straight to the HQ of 8 Mountain Division. After I met Gen. Rao, another helicopter landed there and out emerged Gen. Sagat Singh. The Corps Commander had a half hour discussion with Rao and then I was called in and told to act as the eyes and ears of the Division. I was also told that some more MI4 helicopters were arriving and I was to take charge of them too.

A little later on the same morning, General Sagat called me again and said that the enemy at Sylhet wanted to surrender and since our ground forces were not close enough, I was to fly to Sylhet, accept the surrender and bring him the instrument of surrender. It was a great moment and an honour and I was thrilled that he had chosen me for this task. On the seventh morning I got airborne and went towards Sylhet where I saw a dead town with not a soul stirring in the open. I did two orbits around the town and then flew to the Sylhet airport, expecting the Pakistanis to be lined up, waiting to surrender, but saw no one. I had half a mind to return but then against my instincts and better judgement decided to land thinking that the enemy troops were hiding under cover and would emerge once they saw the helicopter land. I was just about to touch down when I heard the rattle of machine guns from all directions and bullets striking the fuselage of the helicopter. This time, I followed my instinct. I came up on the collective, opened throttle and got away, flying low level between the trees and out of range of enemy fire. I did not know the extent of damage but managed to climb to 4000 feet. I once again observed the airfield and saw no movement and had half a mind to try to land once again. Better sense prevailed and I returned to Shamshernagar. I then drove to the Divisional Headquarter. General Sagat too had come there which gave me an opportunity to accost him.

“Sir,” I said to the Corps Commander, “I have just returned to Sylhet but the only reception I got there was ahail of bullets and my helicopter is perforated with bullet holes”.

General Sagat Singh did not bat an eyelid. It did not make a difference to him whether I was hit or not. “In that case,” he said, “we launch a heliborne operation against Sylhet”. He did not express any sympathy or even apologise that the information about the garrison wanting to surrender was incorrect. Sagat was that very rare breed of men who had only the mission in mind regardless of all else.

It was this single minded purpose that led to the miraculous crossing of the Meghna a few days later and from thence to the gates of Dacca. The Army Chief, Sam Manekshaw spoke to Sagat on 12 December and told him that he was making arrangements to give him the resources to cross the Meghna River. Unknown to the Army Chief, Sagat had used the meagre resources available to him to help lift 1,628 troops across the Meghna and land them in Narsingdi, with their arms, ammunition, mortars, artillery and rations, using 135 sorties from 11th evening onwards! And a bemused Army Chief was told that the Indian Army was already across the Meghna and knocking at the gates of Dacca!

But his greatest achievement is the one that has received the least attention, and that is on 22 Dec 1971, less than a week after the surrender of the Pakistan Army, he handed over full control of the administration of the newly liberated country to Mr Tajuddin Ahmed, the interim President of Bangladesh who had arrived in Dacca just that morning. He did this against the wishes of Gen Aurora who was trying to position his Advance HQ along with a team of babus in Dacca so that he could exercise plenipotentiary powers over the country. Sagat politely sent the babus back to India saying that India’s role was now only to provide security to the elected government of Bangladesh which was the only legitimate authority and the Indian Army was fully capable of providing security. At no time should the people of Bangladesh feel that the Indian Army was an occupying army. This action ensured that when Sheikh Mujibur Rehman returned to Dacca on 10 January1972, he returned to his country that was governed by its own government. This was a remarkable achievement, deserving of the highest praise and acknowledgement which Sheikh Mujibur Rehman did in his speech on 12 March 1972 at the parade by 4 Guards to mark the return of Indian Forces to India. The Americans, even after decades of entering Afghanistan and Iraq are still mired in the civil war, whereas Bangladesh, under the leadership of the present Prime Minister has become a democratic and prosperous state free of internal strife.

After the war, in spite of his formidable war record he was passed over for promotion and several officers junior to him whose record was acknowledged by all to have been pedestrian were promoted. This raised eye brows then and continue to do so even today. The reasons are however not far to seek and they had nothing to do with him and his ability. It was pure and simple envy. His relations with both Manekshaw and Aurora were far from cordial if not outright hostile. The political leadership and others in the ruling establishment viewed him as a very strong personality who would not be amenable to their diktats. The measure of envy that Sagat aroused in some sections of the army’s leadership can be gauged from General Jacob’s writing in his memoirs. Jacob claims sole responsibility for making Niazi accept the terms of surrender in spite of India only having a few hundred troops outside Dacca. Jacob is being very disingenuous; he knew it as did everybody else that by last light of 14 December, Sagat had concentrated all three brigades of 57 Division and one brigade of 23 Division, supported by two squadrons of tanks in and around Dacca. This force was then joined by 2 Parachute Battalion on the morning of 16 December. Niazi had already thrown in the towel on 12 December, knowing full well that all he had to defend Dacca was for the major part composed of administrative and headquarter staff and supply units.

The fear of strong military leaders verged on the paranoia in those days for nearly all countries in the world except for those in North America, Western Europe and India were governed by military dictators. Till today, it is this factor which sometimes plays a role in the selection to the highest ranks in the defence forces. General Sagat Singh was not the only victim of this unfounded paranoia; at about the same time, Lt Gen. Prem Bhagat, VC, the most competent and loved general we had in the army was denied promotion to the post of Chief of Army Staff. A decade later the same thing happened to Lt Gen SK Sinha, who was passed over and his junior appointed who acquiesced with the plans for Operation Bluestar, which Gen Sinha had opposed.

Denial of promotions and honours that were justifiably his did not affect Sagat’s commitment to whatever work came his way or which he undertook both during the remaining years in service and later. After retirement he worked tirelessly with a charitable trust started by Shri Trilokidas Khandelwal, the head of one of the oldest and original business family of Jaipur. Together they were able to convince and influence the then Prime Minister, Smt Indira Gandhi to start the scheme of old age pensions for the needy, poor and aged. This has now become one of the most important welfare schemes of both the Central and state governments. To me both during service and afterwards he was specially kind and I spent many evenings enjoying his hospitality and conversation. They remain my most precious and treasured memories.

Recognition of Gen Sagat Singh is also recognition of all veterans of both India and Bangladesh who fought for the freedom and liberation of a long oppressed people. Our blood and the blood of our comrades in arms the Mukti Bahini is forever united in the soil and rivers of Bangladesh and may it ever remain so as a testimony to our eternal friendship and shared heritage and history.

Commissioned in 4 Guards, Major Chandrakant Singh, VrCis a veteran of the 1971 Bangladesh Liberation War, where he was wounded and awarded the VrC for conspicuous gallantry and courage displayed throughout the war. Popularly called ‘Paunchy’ by his friends, he took premature retirement in 1977 and is now involved in writing and speaking on environmental and defence related issues.