Organisational fitness is judged by purpose. Political parties exist to win elections, not debates. Schools exist to impart education, not knowledge. The British Indian Civil Service existed to rule, not govern. Militaries exist to prevent wars and win them. The Indian Civil Service exists to end poverty, not pay pensions.

Many factors sabotage the public service outcomes that reduce poverty, but a dysfunctional Human Resources (HR) regime for civil servants is surely one of them. Reform won’t be easy or swift. But copying three HR practices from our military in hiring (fixed-terms for successful candidates), specialisation (compounding skills over decades), and structure (performance management forced via a frozen pyramid) will significantly improve civil services fitness for purpose.

Let’s reflect on national goals and strategy before diving into execution. There are no poor people, only people in poor places. The war on poverty is won by raising the productivity of five physical and conceptual places — states, cities, sectors, firms, and skills. Our strategy for replacing our high employed-poverty with high-paying jobs — urbanisation, formalisation, industrialisation, financialisation and human capital — has new policy weapons like GST, IBC, MPC, UPI, DBT, FDI, PLI, NEP, EODB, privatisation, etc. But we also need better HR in civil services because wars are fought with weapons but won by people.

Reform won’t be easy or swift. But copying three HR practices from our military in hiring (fixed-terms for successful candidates), specialisation (compounding skills over decades), and structure (performance management forced via a frozen pyramid) will significantly improve civil services fitness for purpose.

Norman Dixon’s On the Psychology of Military Incompetence suggests generals ignore people and facts that don’t conform to their worldview, learn little from experience, and cling to rules when flexibility is needed. This stereotype is unfair. Clausewitz suggested “Friction differentiates actual war from war on paper and small surprising things make even the simplest thing difficult”; Rommel knew “sweat saves blood, blood saves lives, but brains save both” and Maneckshaw believed “moral courage is the ability to speak up irrespective of consequences to yourself”. The Indian republic has greatly benefitted from civilian control of the military, but it’s time for the civil services to learn three cutting-edge HR practices from the military.

Tenure

The courageous Agniveer revamp — a fixed tour of duty for soldiers which ends with 75 per cent exiting with a lump sum and 25 per cent selected to stay on — will reduce an average soldier’s age, ensure motivation with a conditional light at the end of a long tunnel, and gradually raise military capital expenditure.

This upfront hard coding of painful but inescapable “fitness for next stage” judgements allows organisations to renew themselves without drama, court cases or a huge pool of “promotable but not postable”. While adopting the Agniveer for military officers needs discussion because of the applicant quality shortage, the government must hire all new civil servants for a fixed 10-year tenure with rollover percentages decided by a hard-coded organisational structure.

Specialisation

Bureaucrats often give me the book Range by David Epstein because of its compelling case for generalists. But a democracy’s generalists are politicians; civil servants are technocrats whose mandate changed from ruling to assisting governing in 1947. As the Fulton Report suggested 50 years ago about the UK’s Civil Services, “the philosophy of the amateur is ill-equipped for the age of atomic energy and jumbo jets.

The ideal administrator is not the gifted layman who frequently moves from job to job within service and can take a practical view of any problem, irrespective of its subject matter, in light of his knowledge of the government machine”. This insight is hardly unique. Successful recent business professionals — N Chandrasekaran at TCS, Aditya Puri at HDFC, Varun Berry at Britannia, and Sanjeev Mehta at Unilever — were not industry migrants, dilettantes or polymaths but spent decades in one industry creating intuition, knowledge, networks and humility. Young military recruits pick an area of expertise early, our civil services must replicate this.

Structure

The “on-paper” performance management systems in civil services have collapsed; only a microscopic minority don’t get the top grade through indiscriminate promotions. But treating a gadha and godha as equal makes the gadha celebrate while the godha gets frustrated. Top heaviness also undermines organisational effectiveness; the pyramid has become a cylinder and is morphing into a mushroom; Uttar Pradesh has roughly 80 DGs and additional DGs for around 2.5 lakh policemen, while the army has about 175 lieutenant generals for about 12 lakh soldiers.

Organisational structures should be Eiffel Towers because more work doesn’t mean more bosses. The military is hardly immune to top heaviness but has been more disciplined; cynics say this is only because the civil services prescribes a medicine it doesn’t take. The best solution for differentiation in civil services is honest appraisals, but that’s unlikely to happen. So we must use organisational structure to restrict the secretary rank population in New Delhi to 25, chief secretary/DG rank in states to two, introduce differential retirement ages based on rank and shrink the number of ministries/departments.

Organisational structures should be Eiffel Towers because more work doesn’t mean more bosses. The military is hardly immune to top heaviness but has been more disciplined; cynics say this is only because the civil services prescribes a medicine it doesn’t take.

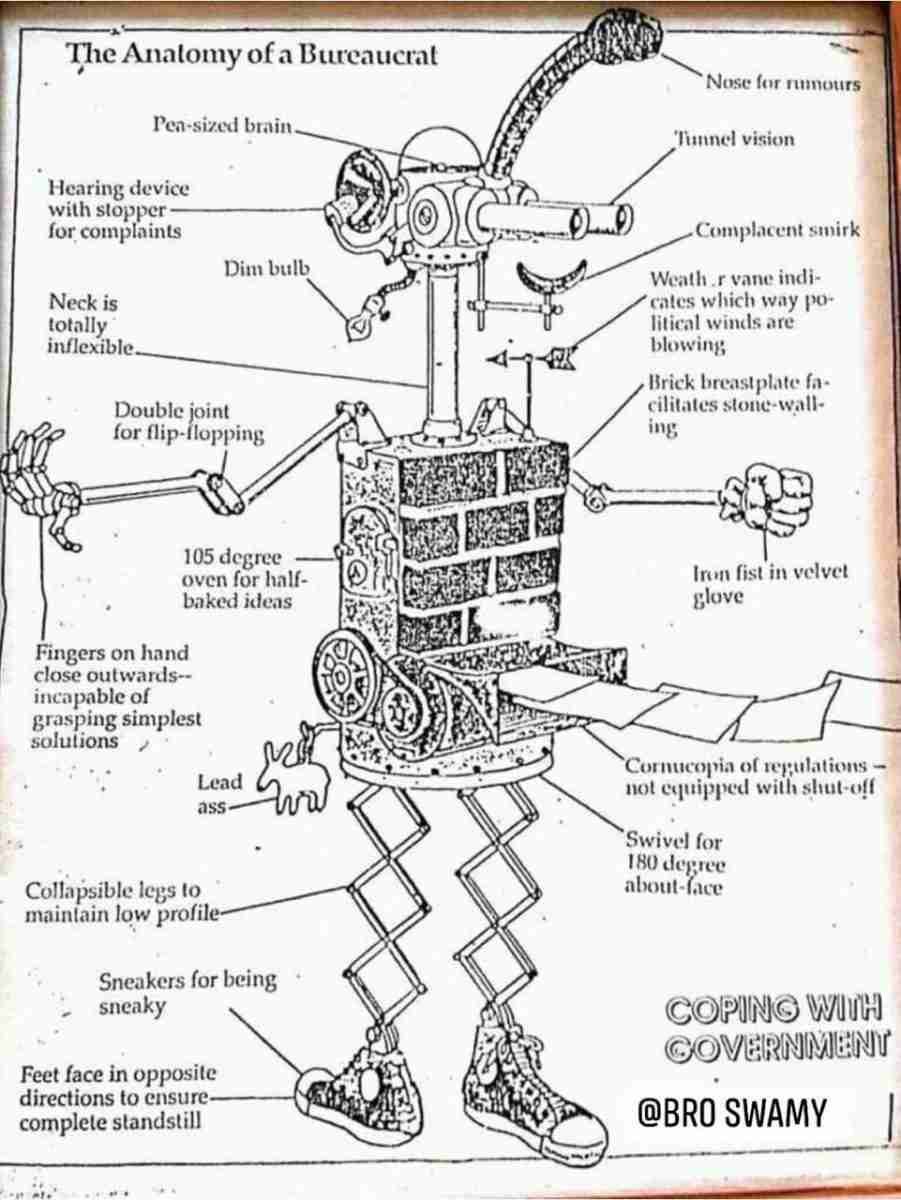

Political theorist Bernardo Zadka describes the popular conception of bureaucracy’s rules (innumerable, entangled, impenetrable), physical attributes (fluorescent-lit, identical chairs, flimsy partitions) and people (distant, unconcerned). Like most stereotypes, this is interesting but incomplete.

The saint or sinner classification in India’s lack of high-wage job creation over decades is unhelpful; the government had an execution deficit, the private sector had a trust deficit, and nonprofits had a scale deficit. But the new India is more competitive, aggressive, and meritocratic for entrepreneurs, nonprofits, politicians, cricketers, and actors. Civil servant selection is highly meritocratic, but their careers are adversely influenced by ossified HR practices that don’t punish bad performers and therefore punish good performers.

India’s military, like every organisation, is imperfect. It must reduce what psychologists call a steep authority gradient and improve collaboration with integrated commands. But our army enforces three HR practices whose replication for our 25 million civil servants will create a fear of falling and a hope of rising by raising competition, accountability and uncertainty. To millions of India’s high-wage job seekers and thousands of competent civil servants, that sounds like a gift, not a problem.

-This story earlier appeared in The Indian Express

Manish Sabharwal writes: For civil services, HR lessons from the military | The Indian Express