The scars of the 1962 war with China still run deep within India, especially within the military. In that short war, India faced a humiliating defeat, yet there were innumerable acts of gallantry, many of which were never recorded. One of them was the heroic action of Lt Col Brahmanand Avasthy. A brief background of the situation as existing prior to the Chinese attack in NEFA is in order, so that the action of Col Avasthy can be understood in the correct perspective.

The Background

Not many people are aware that prior to 1959, the Defence of NEFA(North East Frontier Agency, now named Arunachal Pradesh) was neither with the Indian Army nor with the Ministry of Defence. It rested with the Ministry of External Affairs and was managed by the Assam Rifles working under the foreign ministry. Two areas had to be defended here. One was the border in NEFA demarcated by the McMahon Line and the other was Sikkim. The Army was entrusted with this responsibility for the first time in late 1959. This followed the fleeing of the Dalai Lama to India in March 1959 and the consequent build-up of tension along the thinly held front. As no troops were available in Assam for the defence of NEFA, 4 Infantry Division, which was then based in Ambala, was deployed in this sector, its responsibility stretching from Darjeeling in the West to the tri-junction between India, Myanmar and Tibet in the East—a stretch of over 1000 km. 11 Infantry Brigade was allotted to defend Sikkim and it had its HQ at Darjeeling. 7 Infantry Brigade was allotted for the defence of the Kameng Sector. The third brigade, 5 Infantry Brigade was deployed further East and allocated to the vast but relatively secure sector comprising Subansiri, Siang and Lohit Frontier Divisions. HQ 4 Infantry Division was established at Tezpur and was placed under HQ 33 Corps, which came up later and was located at Shillong. HQ Eastern Command, under Lt Gen. SPP Thorat was in Lucknow.

On 4 October, 1962, the operational charge of the NEFA Sector was given to Lt Gen. BM Kaul, who was then the Chief of General Staff. His troops consisted of the two brigades of 4 Infantry Division—7 and 5 Infantry Brigades. Gen. Kaul was not given the command of 33 Corps, but a new corps—4 Corps—was created for him. The new Corps headquarter had neither any staff nor any corps troops units which are an essential part of a corps headquarter. In actual fact, there was no 4 Corps. It was a phantom, a mirage to deceive the gullible. It simply consisted of an ad hoc headquarter with officers being pulled out from other units to control the battle in NEFA. In effect, it was controlling just two brigades.

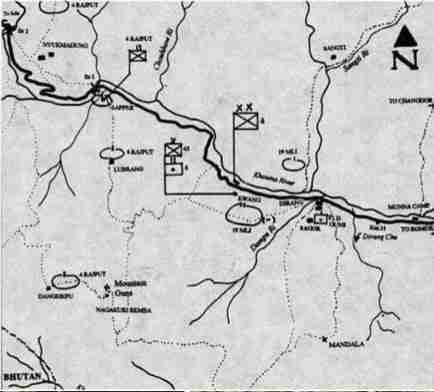

As part of the Forward Policy, 7 Infantry Brigade was ordered to take up defences on the Namka Chu line. 2 Rajput, 4 Grenadiers and 9 Punjab were deployed strung out on the Namka Chu, and 1/9 GR was deployed in depth. The Namka Chu line was overlooked by the Chinese and had no defence potential, but was taken up more to show the flag than anything else. The brigade lacked the wherewithal in terms of weaponry and artillery support and also had a very tenuous foot based logistic maintenance set up. When the Chinese struck in force on 20 October, the Brigade was overwhelmed and disintegrated. Along with the attack across the Namka Chu, the Chinese attacked and overran Bum La, held by the Assam Rifles. This opened up the defences to Tawang, forcing Tawang to be evacuated on 23 October. GOC 4 Infantry Division was removed from command and replaced with Maj Gen. AS Pathania. Maj Gen Harbaksh Singh was made the officiating Corps Commander in the absence of Kaul, who was sick, and 4 Infantry Division took up defences at Se La and Senge. The Se La – Senge complex was to have two brigades; one at Sela and the other at Senge. The Division HQ was 2 km south of Se La on the spur leading to Senge.

On 29 October, Lt Gen. BM Kaul returned as the Corps Commander. An unfortunate effect of this change was that Gen. Anant Pathania, the GOC of 4 Infantry Division got Gen Kaul’s approval to shift his HQ from Se La to Dirang, which was a further 20 km South of Senge. He split 65 Infantry Brigade, earmarked for the defence of Senge, between Dirang and Senge, rendering both unviable and also weakening the defence of the Se La complex. After a tactical pause, the Chinese struck again on 17 November, causing GOC 4 Infantry Division to hastily abandon the defences at Senge and Dirang. The GOC 4 Infantry Division ordered the withdrawal of the brigade at Se La, though here was no alternate position to fall back too. The division then disintegrated.

Induction of 4 RAJPUT

In October 1962, 4 Rajput was located in Belgaum. After the setback at Namka Chu, the unit was ordered to move to NEFA. On 23 October, the unit reached New Misamari in Assam, travelling via Pune and Barauni. The unit was sans a Commanding Officer and was being commanded by the Second in Command, Maj. Trilok Nath who was officiating as the CO. The unit strength was 8 officers, 18 JCOs and 575 other ranks (OR) and was ordered to occupy defences to cover the western flank of Bomdi La, with 1 Madras being tasked to occupy defences to guard the Eastern flank. But on arrival at New Misamari, the unit was reassigned to move to Dirang and was placed on the orbat of 65 Infantry Brigade at Dirang, under the command of Brig G.M.Saeed.

The scene at New Misamari was a picture of chaos, with desperate demands being made for troop labour. 1 ton trucks were plying and were being grabbed by whoever needed it. 4 Rajput, for the most part moved by foot to Dirang, but Major K.P.P.Nair managed to get four vehicles to carry some of the heavy baggage.

It was ‘D’ Company under Maj. P.L.Kukrety, which was the first to reach Dirang. The Company Commander was personally briefed by the GOC, Maj Gen. Pathania and asked to defend the left flank of the Division, covering the approach from Orka La-Punsum La. Kukrety moved his men quickly and reached his position in one day instead of the expected three, moving non-stop to cover the 30 km distance interspersed with ridges and rivers in just 28 hours. They quickly dug in positions and sited their MMG section and 3.7 in howitzer. A section of mountain guns under Captain Ghosal were deployed to assist ‘D’ Company. They were situated 1 km from Dangsikpu. A platoon from ‘C’ Company under Naib Subedar Ranjit Singh was sent with the guns.Over the next few days they witnessed the remnants of Brigadier Dalvi’s brigade filtering through. In spite of not getting permission to register his guns, Major Kukrety went ahead and ranged them.

‘C’ Company of 4 Rajput was detached and placed to protect the Divisional HQ at Dirang. ‘A’ Company, commanded by Maj. K.P.P.Nair was tasked to move along track Nyukmadong, East of Point 3011 – Tangyapand, which was again reflective of the piecemeal manner in which deployment was carried out.

In the above circumstances, Lt Col Brahmanand Avasthy arrived and took over as the CO of 4 Rajput. He was posted from The Infantry School, Mhow, where he was a Senior Instructor for the Junior Command Course. Prior to his tenure at Mhow, he was the Adjutant at the Indian Military Academy, Dehradun. There appeared to be serious command deficiencies at the level of division and above, but Col Avasthy, freshly posted in as the CO, went methodically about building cohesion in his unit.

Col Avasthy was slated to take over 2 Rajput, which was the battalion he was commissioned in. But before he could get there, the unit had been decimated at Namka Chu, so his posting orders were changed and he was directed to assume command of 4 Rajput. The Colonel was considered one of the finest officers in the army. A thorough professional, he quickly got into stride and even before he reached the battalion location, he sent a long note to Major Kukrety, advising him on the siting of guns and MMGs. He also gave advice to the quartermaster on the nuances of running the logistics which he considered the most important aspect of keeping a battalion finely tuned.

In the meantime, ‘A’ Company, which was tasked to prevent any infiltration attempts by the Chinese to cut off the routes of withdrawal of 4 Infantry Division, had to traverse through mountainous dense forests at 10,000 to 14,000 feet. The paths were 3 feet wide, and the thick fog restricted visibility to about 5 meters. Porters were not available so troops had to lift all the loads which considerably slowed them down. By 12 November, Nair had reached his position near Pt 3446. With him was a young artillery officer, 2/Lt Choudhary of 6 Field Regiment. The artillery tried to register the guns, but the smoke from the explosions could not be seen due to thick vegetation and so Nair had to be satisfied with registering only the mortars.

Meanwhile a patrol of 1 Sikh had reported enemy activity at Luguthang village. On account of this, Maj Nair was asked to send out a patrol under Naib Subedar Rai Singh. He was directed to send 2/Lt Choudhary along with the patrol, to act as the FOO. The patrol completed its mission, but Choudhary, while returning, insisted on a break to brew tea. Rai Singh was the patrol leader and he protested, but the young officer insisted, so Rai left a section behind with the officer and continued. This was unfortunate as there was a group of Chinese soldiers nearby, which spotted the smoke and wiped out the section, along with the officer. Only one man, Sepoy Ganga Din, made it back to tell the story.

To follow up on the 1 Sikh patrol, a strong composite force consisting of a company of 2 Sikh LI, and two platoons of 4 Sikh LI and 1 Sikh LI making a total of 200 men was also despatched. The patrol crossed the Luguthana-Kya La line and headed North East. It planned to climb the highest ridge to get a commanding view of the area to harass and interdict the Chinese. But it was dark as the patrol reached the foot of the ridge and this composite group halted for the night, taking up a defensive position. Unfortunately, this group too was spotted by the Chinese and attacked at night. Despite putting up a heroic defence, the group lost 63 men and the rest fell back in confusion.

The news of the ambush stunned the Brigade HQ, but that did not deter them from continuing with aggressive patrolling. A party of 4 Rajput under Naib Subedar Man Singh encountered the Chinese in the Jalak Pu area and on hearing the news, Major Nair rushed in to reinforce his men with his two remaining platoons. The engagement continued for some time before Nair was asked to pull back to his original positions. The Chinese suffered some casualties and retreated to find another way around this point. This was in keeping with their tactic of maintaining their objectives which was to get into positions behind Indian lines to cut of troops retreating from Se La.

Col Avasthy during this period, continued to improve the defensive posture of his battalion, despite the fact that at the Corps and Division headquarters, there were frantic debates taking place, whether the defences at Se La should be held or abandoned. Col Avasthy pulled back ‘C’ Company less a platoon from Lubrang and deployed this force on Point 2898. ‘B’ Company under Maj Mulay had also occupied Gompacher.

The Battle of Lagyala Gompa

At this time, the decision to withdraw from Se La was given, which compounded the prevailing confusion. As 62 Infantry Brigade was to fall back from Se La, it appears that Col Avasthy decided to defend Bridge 1, to allow 62 Brigade and the remnants of 4 Infantry Division to retreat.

On the morning of 18 November, at about 0730 hours, HQ 65 Infantry Brigade gave orders to 4 Rajput to withdraw. Accordingly, Col Avasthy ordered his companies to fall back to the unit headquarter area, near Sapper Camp.

‘D’ Company however found a large number of Chinese soldiers interspersed between the company location and the battalion HQ, so Maj Kukrety was told on radio by Col Avasthy to withdraw to the foothills independently. ‘C’ Company deployed at Labrang had also been attacked by the Chinese at dawn, but the company held firm. ‘A’ Company under Maj K.P.P Nair had been tasked to hold fast in their position, Nair also being told to assume command of all troops North of the road. A subsequent message from Col Avasthy modified those orders. Nair was now told that the battalion HQ was withdrawing and that he should withdraw independently to the foothills. After this communication, Nair lost wireless contact with the battalion HQ.

At 3 am on 19 November, Col Avasthy pulled out of Sapper Camp. He had with him elements of ‘B,’ ‘C’ and ‘D’ companies and he planned to link up with ‘C’ Company waiting at Labrang. There were seven officers in all. Besides Col Avasthy, the group consisted of Major Trilok Nath, Major Y. Tandon, Captain Dayal Singh, Captain S.K.Mitra, Lieutenant D.S.Brar and Second Lieutenant Chatrapati Singh. Up till now, all the sub units of 4 Rajput had fought cohesively, and had facilitated the withdrawal of the troops from Se La, holding back sporadic Chinese attacks. But there was no orderly withdrawal of 62 Infantry Brigade; its broken elements had already filtered through other routes.

With Dirang having capitulated without a fight and Bomdi La having been overrun by the Chinese, Avasthy decided that the best option available to him was to move with all the troops available to him into the foothills, via the Manda La heights, through Phudung and Morshing. Destroying all the stores that could not be carried back he moved to Phudung, where he was joined by various stragglers, swelling the number of personnel with him. Many of the stragglers were wounded and had to be carried, the CO himself carrying the medical officer who was snow blinded.

The column crossed Phudung on 21 November. The Chinese had declared a unilateral ceasefire from midnight that day, but that did not impact the troops on the ground. The Commander of China’s 154 Regiment (419 Unit), had ordered his men to ruthlessly gun down any surviving Indian troops, so the ceasefire made little difference to the retreating Indians. Two days earlier, on 19 November, a sizeable Chinese force had crossed Rupa from the direction of Tenga and headed towards Morshing in the hope of trapping the last remnants of 62 and 65 Infantry Brigades that might escape on that route. It was this force that would battle the withdrawing remnants of Col Avasthy’s column.

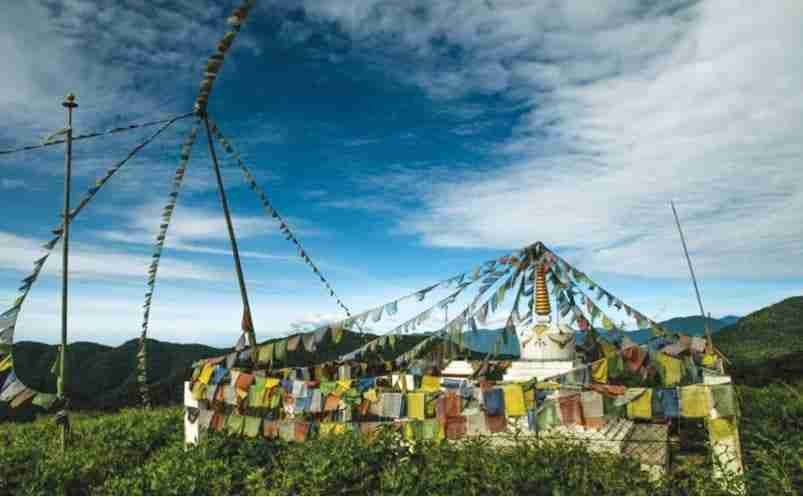

In the early hours of 23 November, Col Avasthy reached Priyuding, a tiny hamlet at the mouth of the Morshing bowl. From here, the main track led directly to Morshing, along relatively flat ground. But there was another track which took a loop via the Lagyala Gompa monastery, and then dropping to Morshing. This involved a steep climb to the Monastery, which overlooked Morshing.

Col Avasthy, after a hurried discussion with his men decided to move with part of his troops via the Lagyala Gompa and directed the remaining two-thirds of the force to go on straight through Morshing. This was tactically sound as should the Morshing group be ambushed, Col Avasthy was in a position to come to their aid from a flank.

The climb to the top of the Gompa was steep and took the best part of seven hours. By this time, the other group had safely gone through the Morshing Valley. Unbeknown to Avasthy, the Chinese were waiting in strength at the Gompa. They probably let the Morshing group pass unhindered as they were lying in wait for the column which was climbing towards them.

It was at about 11 am that Col Awasthy’s column crested the plateau. From here, the track made a steep climb to the monastery. It was at the plateau that the Chinese had sited their ambush and were lying in wait. And from well concealed and protected positions they opened up a barrage of withering fire on Col Avasthy and his men.

The Indian’s retaliated but they were in a hopeless position. Out in the open, moving uphill after a strenuous 7-hour march, and outgunned, the odds were heavily stacked against them. But what they did not lack was courage and leadership.

Rallying his men around, Col Avasthy returned the fire and the battle raged, with only the midday sun as witness. There were under 200 men with Col Avasthy and the Chinese were about 500 in number, but nothing mattered at this moment to the troops of 4 Rajput other than to fight from where they were. Sans mortar and artillery support, they had the option to break contact and withdraw downhill, but perhaps such a thought did not even strike the CO. He was not a man who would just walk away from the battlefield. He was a man who would take a stand for the honour of his men and for the safety of his country. Col Avasthy chose to fight. He chose to take the final stand.

Col Avasthy launched a counter attack on the waiting Chinese who doubtless must have been surprised at the resistance put up. For the next two hours the battle raged, with no quarters asked for and none given. And the battle raged relentlessly, till the very last soldier of the brave 4 Rajput column, lay still on the battlefield. The exact number of soldiers who died on the plateau that day will perhaps never be know. What is known is that they fought to the very bitter end, each and every one of the 170 or so troops who took part in that fateful last stand. This battle is not well known though it merits to be emblazoned across the pages of Indian military history. In terms of courage, it was no less than the heroic last stand put up by the Sikhs in the Battle of Saragarhi. Or of the last stand by the Vir Ahirs of 13 Kumaon in the Battle of Rezang La. But in the forlorn mountain top where the battle of Lagyala Gompa took place, there were no witnesses, no one to write about the heroism that was on display that day, where every man went down fighting to the very bitter end for his country. Each and every man laid down his life, to include all seven officers who were with the column, as also their leader, Col Brahmanand Avasthy. No country could have asked for more from any of their brave sons.

The Chinese did not have it easy, despite having an overwhelming superiority in numbers. They also had the advantage of surprise, of being on higher ground and protected, and being

vastly superior in the quality and number of their weapons. The casualties suffered by the Chinese were not light. As per some reports, some 200 Chinese were killed on that winter afternoon. They stacked their dead in the small courtyard of the Gompa and then took the bodies, loading four to a mule or yak, and then moving the long mule and yak column to Dirang Dzong, where they were reportedly cremated.

In deference to the Indian dead, who had put up such a heroic resistance, the Chinese dug a mass grave and left a flattened ration tin with the names of the officers killed in action. This was a mark of respect to the bravery, valour and courage shown by Col Avasthy. It was left to Maj Kukrety to return at a much later date to this spot, and have some of the bodies of the Indian soldiers exhumed. Kukrety had successfully exfiltrated with his company across the Bhutan border and on his return to the Gompa, well after the ceasefire, found the grave, where most of the bodies had decomposed. From the pocket of Col Avasthy, he recovered a blood stained letter written to his wife and a piece of paper inscribed with a prayer.

The lone witness to this heroic action was a shepherd boy, who later became the Head Lama of the monastery. The story of the last stand by Col Avasthy obviously must have been of such great import that it prompted the villagers to build a grave in memory of a man whose heroism had become legend to them. In 1989, Mrs Sushila Avasthy visited the area and went to pay her respects to her brave husband. She stopped her jeep at a bridge in Dirang, where some local people had gathered and beckoned to a young girl, asking her if she knew the directions to Lagyala Gompa.

“Yes,” replied the girl, “we go there for our spring festival and offer flowers on the grave of a Tiger, who is buried there”. That Tiger was none other than Col Brahmanand Avasthy. To be remembered by the locals to this day, speaks more than any number of words which can be put in print. Col Brahmanand Avasthy and his men fought till the last man and the last round in the highest traditions of the Indian army, on that fateful afternoon of 23 November 1965, on a lonely plateau leading up to the Lagyala Gompa. But heroes can never die. That pain is for us lesser mortals. The brave live on, in the memory of those left behind—a memory which goes across the ages to the generations yet to be born. And it is on the sacrifice of these brave hearts, that we, who have come after them, taste the sweet breath of freedom.