Introduction

On November 8th, Prime Minister Narendra Modi announced the demonetisation of existing currency notes of Rs 500 and Rs 1,000. The declaration was immediately followed by panic, chaos, and excitement in the country. In the recent years, there seems to be no precedent globally of a country attempting such a measure. Currency in circulation accounts for 14 percent of the GDP in India, whereas in most other large economies it is less than 5 percent of the GDP. The Rs 500 and Rs 1,000 notes which have ceased to be legal tender comprised nearly 86 percent of the notes in circulation. The increase in the circulation of these notes in the past five years has been disproportionate to the economy’s growth. The reason advanced by the government for this measure is to fight counterfeit currency and provide a stable formal economy by curtailing tax evasion. The efficacy of this move will depend upon the extent to which black money is held in the form of high-value currency notes of the specified denomination.

The only other time in India’s economic history when a demonetisation measure was taken up was in 1978 by the Morarji Desai government. In 1978, the government had decided to scrap Rs. 1,000, Rs 5,000 and Rs 10,000 denomination notes. The overall impact of this measure in the ordinary lives of the citizens then was negligible because the scrapped currency only comprised 1.8 percent of the total money in circulation.

The distress for the common people

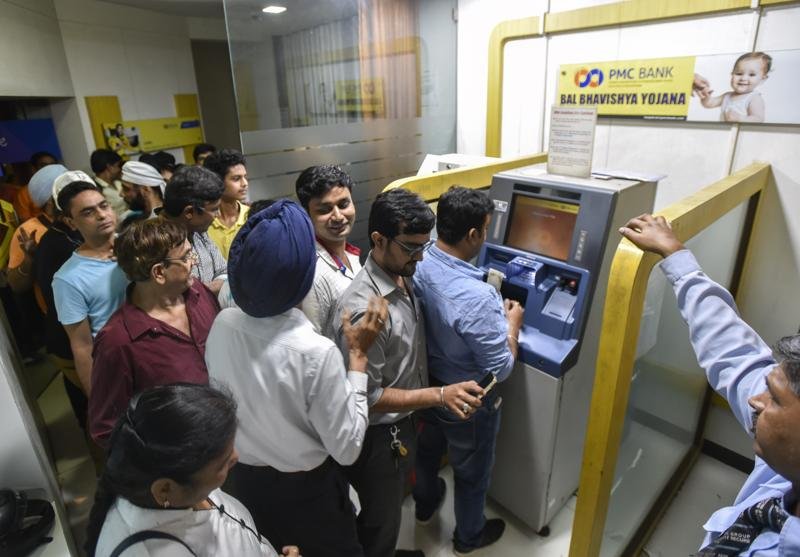

Since the announcement was made, there have been reports of cash shortage, long queues outside ATMs, and hardships due to inability to buy daily items. For most supply chains that deal with perishable and lower value goods, the disruption is likely to last longer than the time taken to normalise the currency availability. Over a hundred deaths have been attributed to demonetisation, till the end of December, though it is not entirely certain whether the deaths that took place had a direct co-relation to the demonetisation exercise. As per media reports, some of the deaths occurred due to exhaustion after standing for hours in long queues, but as very few of these deaths actually occurred while standing in queues, the authenticity is not confirmed.

Demonetisation is expected to adversely affect those sectors which have linkages to the unorganised economy. The market for consumer durables and non-durables is also likely to be affected in the short and medium term as large denomination purchases could be made online rather than through brick and mortar outlets. As per several economic experts, in the short-term there will be a negative impact in cash-intensive sectors such as real estate, construction, and discretionary household consumption. As for its political implications, opposition parties, will use this opportunity to attack the government. On November 28th, opposition parties, held a ‘protest day’ across the country to highlight the distress faced by the common man due to the demonetisation move.

It is also predicted that if not managed well, this measure could also lead to an artificial recession in the economy. Even civic bodies in some cities like the BEST buses in Mumbai, a, vital mode of public transport for lakhs of commuters daily, had refused to accept Rs 500 and Rs 1000 notes.

ATMs across the country have also repeatedly failed to meet the high demand for currency. ATM machines in most places were dispensing mostly notes of Rs 100 denomination while some were stocked with Rs 500 notes. The lower denomination notes available at the ATMs meant that they kept running out of cash at frequent intervals. The banks also had to recalibrate the ATMs to dispense the new currency notes of Rs 500 and Rs2,000, which are of different size than the previous currencies. The government’s assurances on cash availability and extension of deadline for government services to accept old currency notes for payment did little to mitigate the situation on the ground. In addition, there existed some confusion for the people over the use of old currencies in transactions for a limited time, as the RBI had issued 27 circulars in 14 days (till November 22nd), since the policy was announced.

The positive impact of demonetisation

On the positive side, the measure has boosted transactions through payment gateways; mobile wallets and online retails. If properly implemented, it is expected to send a strong signal about India’s anti-corruption drive. It could also help to accentuate the government’s financial inclusion drive, as more households will move towards efficient banking and payment infrastructure. Economists have predicted that the bank deposits base is expected to increase by 0.5 – 1.4 percent of GDP. There will also be a switch from savings of unproductive physical assets to financial assets. NITI Aayog vice chairman, Arvind Panagariya, stated that demonetisation will help to lower inflation in the country in the future. The demonetisation drive will also help to boost cash deposits in the Jan Dhan

accounts,of which 43 percent have remained dormant in the last two years.

The demonetisation move quickly caught the attention of foreign media and several columns in leading newspapers were dedicated towards highlighting the move. Prime Minister Modi’s move was compared to a similar step taken by the European Central Bank which has discontinued the use of 500-euro notes to stop their use in illicit activities. The plan, kept top secret until Mr. Modi’s announcement, was hailed by financial analysts as bold and, potentially, transformational for India. If the reforms work, in theory it could broaden the government’s tax base. The sale of Indian bonds, which are highly popular among emerging-market investors, have increased since the announcement.The International Monetary Fund (IMF) spokesman Gerry Rice said that the institution supports the measures to fight corruption and illicit financial flows in India.

Conclusion

In terms of addressing the black money issue, demonetisation will be ineffective if it is a one stop solution. It must be backed by monitoring and investigation by the Income Tax departments and the law enforcement agencies. For now, the short-term hardships caused by this policy seems to overshadow the proposed long-term impacts.

Arpita is an Analyst at MitKat’s Information Services Team. Before joining MitKat she worked as a Research Assistant at IIM, Bangalore. She completed her M.A. in International Relations from the Jindal School of International Affairs.