Part I of this essay emphasized on getting the background right, for without that a complex nation such as Pakistan cannot be understood. Nations with a propensity to pursue the path of hara-kiri need a deep study of their psyche. From the exercise of joining the dots of the past it is evident that Pakistan’s problems are five: –

- The undue focus it gave to the military security domain thus imbalancing its planning process in the allocation of resources and more importantly attention towards the well-being of its people.

- The lack of attention to economic planning, especially its food program and manufacturing. ‘Cutting the nose to spite the face’, was so evident from the decisions taken not to involve in serious trade with India or allow India access to the Central Asian Republics or Eurasia through its territory.

- The inability to bring modern education to the fore and discourage radical ideological belief.

- The refusal to address the necessity for a social transformation among its poorly educated masses thus allowing itself to be overtaken by obscurantist ideological beliefs. A mistaken perception that through this route it could lead the Islamic world.

- The obsession with conflict and the belief that sub conventional means would deliver it the desired results especially in dealing with its more powerful neighbour India.

Among other characteristics that Pakistan possesses is the ability of its strategic community and political leadership to initiate turbulence without any vision about the terminal objectives. A serious issue which needs factoring in all assessments is the history of irrationality that its leadership has resorted to in challenging situations. In 1947 it went to war with India with a belief that the Indian Army could not match the prowess of the tribals that Pakistan employed. The same argument was used in 1965, the intent being to capture J&K through a people’s revolt assisted by the Pakistan Army before the Indian Army became stronger due to the refurbishment drive after the military defeat at the hands of China’s PLA in 1962. In 1971 it decided to hold the territory of ‘East Pakistan’ through a virtual genocide of Bengali intellectuals and then went to war with India in the hope of defeating it militarily.

In terms of self-gratification, it probably has the highest levels of corruption in different walks of life. Its political, military and bureaucratic communities are hugely dependent upon graft. There are numerous examples of the level of riches acquired by some in the leadership. The lifestyle of Pakistan Army officers who serve abroad is also indicative of that. A serious commitment to the people is evidently missing.

Thus, if Pakistan has come to the sorry state it is in, it is nobody’s fault but that of its leadership and its people. Given the serious situation of its internal administration, weak governance, a failing economy and a challenging internal security environment, it is a basket case for implosion. We cannot forget that Pakistan possesses nuclear weapons too and this aspect has to be factored into all scenarios as one of the most important inputs.

The feasibility of Pakistan going completely bust with no means of self-administration is yet remote. An informal economy can keep a nation afloat for some duration; Afghanistan is an example of survival of a nation on a minimalist economy. Nations at war for long durations suffer the same. Pakistan could also reach such a stage and only then the seriousness of its plight may be realized. The international community led by the UN, Saudi Arabia, Qatar and the UAE is promising financial aid of approximately 22 billion USD but when that will see the light of day is yet questionable.

It was expected that richer Islamic nations such as Saudi Arabia and Kuwait could rush to Pakistan’s aid. The truth is that the world is undergoing economic uncertainty and ‘me to myself and you to yourself’ appears to be the new mantra. International cooperation is a part of strategic security. Thus, socio-economic turbulence in a high population country with weak social indices, such as Pakistan, should be their concern. However, the post pandemic informal world order seems to be emerging differently. Aid may finally fetch up, but it could be minimalist and with numerous conditionalities tagged to it. It is Imran Khan and then Shahbaz Sharif’s resistance to IMF conditions that has delayed the disbursement of the IMF loan secured in 2019. The IMF has been seeking conditions for disbursement of the loan for three years. Pakistan may not have much choice now.

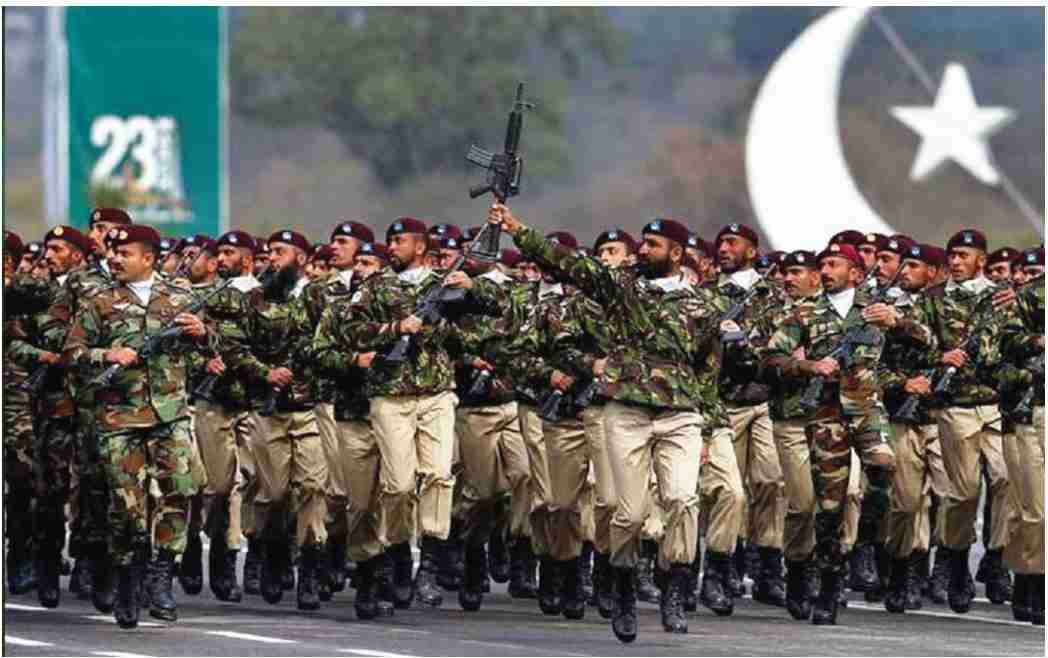

The important thing is that a government must be in place as the incumbent government could well resign so as not to be held responsible for the entire meltdown. We are looking at a nation of 220 million and not a small Middle East country like Syria which had a population of 24 million when civil war wrecked it. Political consensus to establish a government of national unity seems highly unlikely as differences are far too deep set and inimical. Pakistan has a disciplined set of forces under arms but what their attitude and response will be in the face of a calamity which is existential in nature is anybody’s guess. Its unthinkable but the Pakistan Army itself could divide along regimental lines unless its top leadership is ‘united and strong’.

An attempt to drag Pakistan into a warlord situation with division along ethnic and regional lines and boundaries drawn along state borders is not outside the realm of possibility if no outside financial support is forthcoming. To survive, Pakistan must remain united and the only way that seems possible at this stage is a resort to Army rule. In most other cases the international community disfavours a rule by uniformed people. However, in the case of Pakistan they may just about welcome it. The US for example has a long and ‘cherished’ relationship with the Pakistan Army and comfort levels between the State Department and the GHQ at Rawalpindi are cordial and much more.

It should be remembered that there is a fine dividing line in these situations. If economic assistance, food supplies and energy are immediately pumped in along with some financial assistance to surge the economy in whatever way it can, Pakistan could yet cross the hump. However, at some point if meltdown begins then a late resort to economic assistance etc will have little or no effect. From that point onwards civil war conditions will prevail. India’s international border (IB) with Pakistan will need to be sealed in such a situation. Recalling the situation in the then East Pakistan of 1971 India did not seal its borders on humanitarian grounds. However, in today’s security environment allowing displaced persons from Pakistan into our lands will be suicidal. We should be prepared for non-tactical skirmishes along the international border with potential for calibrated upgradation of violence. At some time, a full-scale mobilization may have to be ordered with its consequent implications. Human rights could well mire us into international controversy much as it drew Europe into it in 2015-16. It would test our diplomatic capability plus the quasi military capability of Indian Army and central border guarding forces to their full.

Pakistan is unlikely to seek or even accept any material assistance from India. Neither should any attempt to negotiate any such proposal be made by the Indian side. While humanitarian grounds demand something different the strategic need overrides all else. However, reliance on Track 2 diplomacy and backchannels will always be helpful since all contingencies may not develop as negatively as we may assess. A range of contingencies is possible under all the circumstances explained above. India should analyse these and do a cost benefit analysis to look at potential outcomes. This should be shorn of any emotive and pragmatically look at the advantages India can derive from the actions that it takes.

Among the highest priorities in our consideration should be the need for peace and stability. PM Narendra Modi’s intent of putting India on the path of a ten trillion-dollar economy demands such peace, going into the next ten years. It’s the most cerebral and optimum way of finding peace. It will enable India to develop and build such comprehensive national power that credible deterrence will be possible to be acquired and demonstrated. The temptation to do something, teach an adversary a lesson for his recent waywardness and gain a tactical upper hand, is all temporary. We need permanence in peace and stability.

On reading Part I of this essay many learned readers sent me feedback that India must not commit the same errors it did in 1972 at the Shimla Agreement and thereafter. How right they are. The Shimla Agreement, in terms of Conflict Resolution achieved nothing. It should have put an end to Pakistan’s potential to be a threat. Perhaps India was too young a nation to see through conflict resolution and termination. The Soviets helped us a great deal but it is well known that they indicated to PM Indira Gandhi the limits of their assistance.

The understanding of conflict and its connotations had been insufficiently considered then. A military victory involving the surrender of 93000 prisoners of war, capture of many square miles of territory and the creation of a nation, was yet insufficient guarantee for peace. War without resolution of the problem many times leads to much more enmity and violence in the future. Since the 1971 conflict did not resolve much except the sovereignty of Bangladesh and India was a little overwhelmed by the enormity of the military victory we failed to look sufficiently beyond. Whether there was scope for alternative paths to eventual peace has never really been analysed.

Should India consider Pakistan’s comprehensive weakness of today as an opportunity to weaken it further, let it break apart into weak states with high stakes in peace. There are factors which may argue in favour of such a step. However, we could do well to remember that the Global War on Terror has not yet ended, its in a state of suspended animation. The establishment of supremacy of Islam is the intent of the global jihadists. Another theatre of chaos with diverse Islamist forces would be a gleeful environment for those who wish to see the spread of militant Islam. A below threshold militancy can take unpredictable shape and erupt differently at different junctures and locations. In other words, instead of the peace and stability which India desires for its growth to a well beyond ten trillion dollar economy, a prevailing and unpredictable chaos at our doorstep and perhaps even within isn’t something that supports our belief in India’s future.

What India really needs is a non-emotive analysis. Much that public opinion demands kinetic steps to destroy Pakistan as a nation, pragmatism points at far smarter ways of victory while maintaining our silent march to such prosperity that we could secure full deterrence through a well budgeted hi-tech set of armed forces. That reminds of the Deng Xiao Ping model. The first three modernisations of China involved food sufficiency, technological capability and industrial manufacturing. When these were achieved China turned towards the PLA. Until then the doctrine was ‘stable borders’. The modernisation of the PLA gave China the coercive tool it sought and a noticeable change in doctrine has progressed since then. It was all possible because of the continuous high growth rate that China achieved. The overall balance in modernisation programs also lifted 750 million people out of poverty adding to China’s social stability which it has been unable to sustain due to other mismanagement.

Among the options for India there need not be any offensive military manoeuvres or rhetoric which could exacerbate the situation and draw response. A partial defensive deployment along the borders would caution the Pakistan brass against any irrational steps. The same must be conveyed through effective communication strategy from time to time. India’s non provocation and defensive deployment may draw criticism from many quarters within the nation; so be it. No one in the Indian strategic leadership is spoiling for war; our stance has to be defensive with adequate scope for offensive should Pakistan decide to use the borders and its armed forces to score points from an existential outlook and diversion of internal attention.

Effective communication is the key to the emerging situation. DGMO hotlines are insufficient for such a scenario although initially a thrice weekly interaction between DGMOs and weekly interaction at the sector and sub sector level may help in ensuring the continued stability of the ceasefire at the LoC. Pakistan is bound to move its GHQ reserves into the PoJK area the moment there is indication of any Indian reinforcements. It has to be ensured that mistakes do not occur and that the propaganda machinery in the hinterland is effectively countered by Indian narratives. A special hotline between the NSAs will add further credibility to the availability of communications. The CI/CT grid must remain intact even though there may be very few incidents. We do not wish to create openings and give an opportunity. The jihadi elements will wish to see nothing more than an open clash between Indian and Pakistani forces; this has to be prevented.

Since the last time any conventional standoff took place between Indian and Pakistan forces in 1999, the entire domain of information has gained prominence. India will have to see how best it can use the existing means to develop Indian narratives and dominate the media networks, nationally and internationally. The Pakistan media has softened its rhetoric but this is temporary. Our response should cater both for long term strategic and operational, and the short term tactical advantage. TRPs of the electronic media and high-profile panel discussions of experts need not become the reference points for policy. The Government has enough experience of its own and sufficient resources for advisory. Its popularity is high and its international image is making waves. There is no need for any populist knee jerk response but the process of consultation and wargaming with think tanks and within should give us the confidence to handle and see through the challenges emerging on our western borders.

Lastly, the nuclear realm has of late become a talking point. While we accord all forms of rationality to the analyses that we make and discuss, it may well be worth it to discuss the worst case scenarios for better education and deep professional consideration. Let the nuclear domain not become an arena of disadvantage just because we considered it far too sensitive to educate our senior service officers, academia, analysts, intelligence officials and diplomats. To be of deterrence value it must be seen to be well known and war gamed by the decision makers.