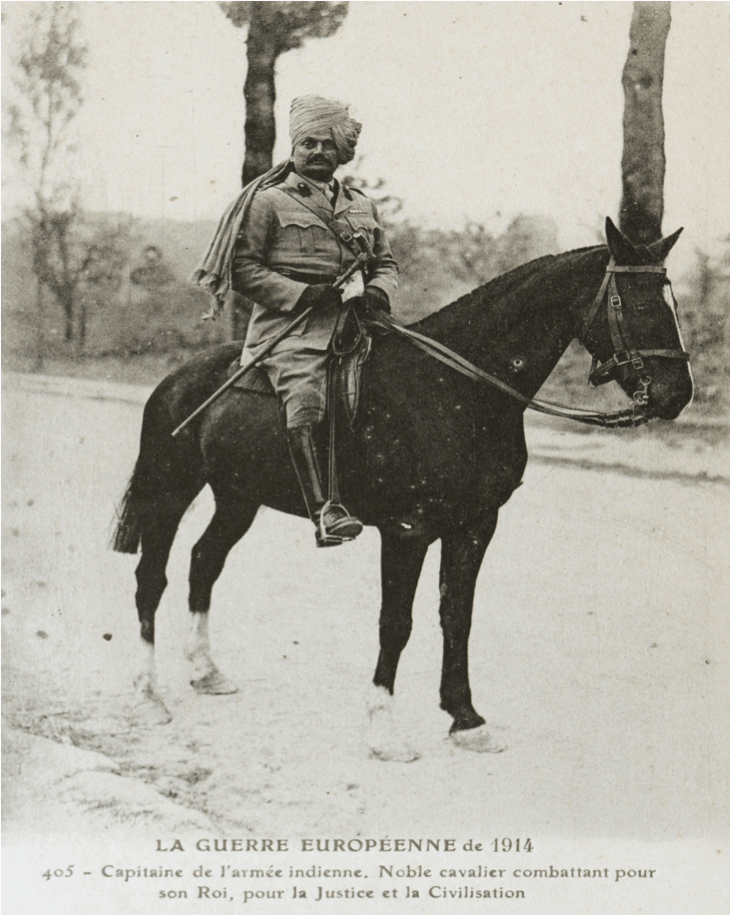

A glimpse into the life of one of the first Indians in the British army, General Amar Singh Kanota.

February 23rd, 1916

… As was expected the Turks had dug trenches in the most favourable spots along the riverbank and the next morning they started shooting against us. They did hit a few people but all the same, it was a source of great amusement to us. We soon discovered their loopholes and shot at them…General Gorringe got hit on the bottom just as he was mounting his horse … Gorringe is a great energetic man and is known as a ‘thruster’. He has also a reputation of being a butcher, as he does not much care about the lives of the soldiers. However, he is a very good soldier.

The above is an excerpt from the diary of General Amar Singh Kanota who belonged to a family of service aristocrats of Jaipur. He began his military career at the age of 14 under the tutelage of Sir Pratap of Jodhpur and rose to the rank of a Rissaldar of the Jodhpur Lancers.

Rissaldar Amar Singh was part of the allied expeditionary force that was sent to China to quell the Boxer Rebellion in 1901. The young officer wrote in vivid detail of his impressions of the wide world before him including some interesting observations of the armies and soldiers of different countries.

Sunday 14th July 1901

Of all the foreigners I like the Russians the most…the Russian cavalry or rather the Cossack whom I had a great opportunity of observing is a true soldier in the truest form.

There is no smartness in him. There is nothing glittering and every small particle he carries is useful. The uniform is quite light. There is no pride in him. They do not have swagger and useless parades… when they first come on the ground the officer stands in the center and they ride at a trot in single file in a circle which is good because the officer can find out whether everyone is in good order or not… they are though great drunkards which is no vice among them. They are all very polite. Some people have not a very high opinion of them but I have.

What followed the China expedition was an invitation to join the Imperial Cadet Corps in 1903 an optimistic yet shortsighted effort by the Viceroy Lord Curzon to provide professional training for potential Indian officers. Of the 21 young maharajas and noblemen who attended the academy only 4 graduated in the first batch Lt. Amar Singh Kanota being among them.

The next opportunity for a tour of active duty came in 1914 when Captain Amar Singh was called upon to fight in the Great War.

August 17th 1914

I received an envelope from Col Stratton the resident informing me that I was detailed for active service and was to report myself to General Brunker commanding the 9th Infantry Brigade at Karachi not later than the 22nd inst… At polo the Resident, Col. Fisher the doctor and Mr Stotherd, the engineer all congratulated me on my good luck being ordered to the front.

Amar Singhji was of a new breed of officers whose place in the army hierarchy was not yet certain. It was not until 1917 that he was given a full King’s commission to the 16th Cavalry. For ten years he served as an ADC to various GOC’s and through the war when the British high command doubted the abilities of the Indian sepoys to fight in the damp and cold trenches in France, Amar Singhji reiterated the principle of Izzat and the dharma of duty, which is in the DNA of every fighting soldier.

September 17 1915

On my visit to the India office Lord Crewe (Secretary of State for India) asked me whether it would be a good thing to move them to a warmer climate. I said that this would be the worst thing that could possibly happen, you do this out of concern for our wellbeing, but in the future some blighter who has no sympathies with us would fling it in our teeth that we were not considered good enough to fight against the Germans and so were sent back, I would rather all us Indians die here, than be sent away and have people say we were too weak to fight on European soil. All men die, and what are the lives of a few thousand compared to the honour of a nation.

When the Indian infantry left France for Mesopotamia at the end of 1915 Capt. Amar Singh went too as an attaché to the headquarters of the 9th brigade of the 9th Division. He left Basra in June 1916 for India where he was appointed ADC to General Knight commanding the Bombay Brigade.

On September 24th 1917 the London Gazette announced commissions of 9 British officers Captain Amar Singh was to join the 2nd Cavalry Gardener’s Horse. He was immediately seconded to the 16th cavalry, as his regiment was still in Egypt, where he remained until he finally left the British service in 1923.

As additional support to the imperial service scheme was promised by the Jaipur Maharaja a cavalry regiment and an infantry battalion were to be raised. Major Amar Singh was appointed as the first Commandant of the Kachhawa Horse in 1923, the headquarters of which now belong to the 61st Cavalry Regiment. Amar Singh ji was with the regiment until his retirement as a Major General in 1936.

He summarized his ideas as commandant in a diary entry on the 23rd of September 1936 As a rule the Indian has a narrow mind. He does not want his subordinates to shine or come to the foreground. I worked on different lines and was more open-minded. I pushed my officers and encouraged them to come to the Club and mix with bigger and better people than themselves. I made them play Polo and other games. I treated them as my own sons. The majority of my officers were not educated and came straight from villages.

As commandant, he was aware of the tremendous gap in the education and experience of his regimental officers as compared to their British counterparts. He was keen to use his knowledge of the Indian army to ensure at least some of his comrades would not face the same discrimination he did and give them opportunities for self-development.

Amar Singh ji read and wrote profusely throughout his life collecting over 3000 books and producing 89 volumes of diaries from 1898 until his death in 1942. As Anaïs Nin once profoundly said ‘we write to taste life twice’ to me he certainly was a man who lived it twice.

His diaries are valuable to me not just for the breadth of time and experiences they cover but also his charming ability to be blunt about his shortcomings.

His personal effects which include his diaries books photo albums among several other things are housed in the General Amar Singh Kanota Museum made in his honour by his grandson Thakur Man Singh Kanota at Castle Kanota in Jaipur.

1916, the Mediterranean Sea

Captain Amar Singhji is on a troopship taking him from Flanders to Basra, to pass the time he reads the famous diary of Samuel Pepys, a British Parliamentarian and Naval Administrator. The captain wonders while writing his own diary, which he has been writing for nearly 18 years, ‘whether in the future someone would ever print my diary and whether anyone would care to read it.’

Major General Rai Bahadur Amar Singh ji, the Third Thakur Sahab of Kanota wrote his diary religiously and read voraciously for 44 years from 1898 to 1942.

Meerut, Tuesday, 5th January 1904

‘These two habits of mine I am trying my best to carry on. They are the writing of my diary and never to read a book by half but always to go through it from one end to the other.’

These simple habits led to a momentous event for the Kanota family one hundred and eight years later in 2012 when his grandson Thakur Man Singhji opened the doors to the General Amar Singh Kanota Library and Museum, which has preserved 89 volumes of diaries nearly three thousand books, eighteen photo albums, Amar Singhji0’s uniforms and various personal papers including a hundred-year-old HSBC passbook of the 22-year-old Rissaldar Amar Singh who went to fight in the Boxer Rebellion.

What is unique to the museum at Kanota is that every item is imbued with life from the perspective and insight we have from the diaries. The museum does not rely entirely on the visitor’s knowledge of history to be interesting, as each item preserved there had a functional and sentimental purpose the visit is oriented more like a walk through Amar Singhji’s thoughts and memories.

For instance, the gallery dedicated to the hunting and sporting section has several photos of the Mhow Polo tournament of 1899, where Amar Singhji plays for the Jodhpur Team. A diary entry from the 24th of November 1899 brings the black and white image to life, ‘…at 2 p.m. commenced the match between us and the Royal Fusiliers. We beat them by three goals and three subsidiaries to one goal and two subsidiaries. Though the game was not so fast as we had with the 3rd Bombay Cavalry yet we won with great difficulty for our arms and legs were quite stiff and we could neither hit hard nor straight.’

(Please refer to image number 2)

It would be remiss to marvel at the depth and length of the effort put in diaries by Amar Singhji without mention of Bharat Ram Nath ji Ratnoo, the man who put him on his trajectory. Ram Nath ji being Amar Singhji’s former school teacher had kept a diary himself while travelling in Europe in 1894. He followed the English School practice of assigning diaries as a means of cultivating discipline, self-awareness and developing moral fiber.

At some point Amar Singhji hands the completed version of the 1899 diary to Ram Nathji to read, the beloved tutor pencils his remarks which Amar Singhji retraces in ink-

‘Sorry to say that though this diary has been written at its end during the months of a great famine of the century yet nothing has been written about it or the suffering of humanity. Very sorry to say that you have left to the world only a record of so many animals killed in such and such a manner. A writer must always bear in mind that it is his duty to give something very profitable to his readers for the time they spend in reading his works. With very few exceptions here and there the diary contains nothing in it worth reading in it except a record of butchery in some form or other. My dear Amar, here was an opportunity for you to devote some part of your time in thinking over the famine and pointing some remedies for the same, thus making the diary not only very amusing but very useful to mankind. Now, don’t you be cross when you read these remarks of him who loves you sincerely.’

To which Amar Singhji replies:

‘My Dear Master Sahib,

I am indeed very grateful for the troubles you have taken to read the whole of my diary and to have written remarks on it. I feel very much honoured by it…though quite rot and record of butchery as you say…I ought surely to have written about the famine but you must bear in mind that no opportunities were given me to study or watch it and consequently I could not write anything and I did not write, fearing that I may put in something quite out of the place. What I have written is of which I am an eye witness or have heard from very reliable sources…’

True to form the diary entries only report that which Amar Singhji himself experiences and being a pragmatic man he does not engage in pedantic lectures of morality his writings are vivid and anything but boring.

In the autumn of 1900 the Jodhpur Lancers sail to the Zhili Provence, north-east of Peking as part of the Imperial effort to put down the Boxer Rebellion. At the northernmost corner of the Great Wall of China, Risaldar Amar Singh garrisons with the Jodhpur Rissala at Shan Hai Kuan, where disturbances have been most pronounced.

4th July 1901, shortly before leaving China Amar Singhji worte summary of his experiences-

‘…The climate was very healthy. There were next to no sick people in our lines. I for myself am greatly improved in health and so is everybody else. The winter was no doubt a very severe one. It was simply too awful. The record is forty two degrees below freezing point…the fruits bread everything used to freeze. The ink also froze twice inside our rooms. The men’s moustaches also used to freeze with their breathing… even sometimes the perspiration used to freeze on the bodies of the horses while they were still hot and working around the course…there was no limit to the clothes we wore. Bathing had become quite scarce.’

Friday 25th January 1901

We heard the sorrowful news of the death of Queen Victoria of England Empress of India. It was quite too sudden. ..

Monday 28th January 1901

After breakfast I borrowed Capt. Hughes’ eye-glasses and taking an orderly with me went to No. 1 Fort on the seashore. There mounting on the highest parapet I had a good view of the sea. Within about half a mile of the shore the ice had melted but beyond it was all frozen hard and the snow having fallen over it, it was glistening in the sun and presented a most lovely sight. Except one, all the other ships were frozen in the ice and quite unable to move. One ship was also firing the minute guns of the Queen’s death…

Tuesday 25th December 1900

(On Christmas Day the Allied Expeditionary Forces arrange a gymkhana)

In the Lloyd-Lindsay race, there were all officers. It was open to all nations…The conditions were that we were to start with empty pistols, dismount, give our horses to our sowars that were in wait for us, load our pistols and fire and try to hit the bottle at a range of twenty-five yards. After hitting the bottle empty the pistol, mount and ride back to the winning post… At the start, we went in good speed. I for myself had taken a handful of cartridges out of my pocket and springing from my horse hastily loaded and fired. By good luck, I broke my bottle at the very first shot. I hastily mounted my horse and came home in an easy canter; I was quite an easy winner…

There were all nationalities assembled British, Germans, French, Russians, Italians, Austrians and Japanese… One very seldom gets to see such a gathering…

In April 1901 the Jodhpur Lancers visit Peking where horse races and various games have been organized for the International Expeditionary Forces. Amar Singh ji wins the International Steeple Chase on his faithful steed Ghatotguch, much to the delight of the British Officers who feared ‘The Germans would win it’

In May 1901 Sir Pratap and the Jodhpur Lancers set off to visit Japan as honored princely tourists, the highlight of the trip is the visit to the court where the Emperor graciously receives the visitors. Amar Singhji concludes that the tour of the far East ‘was of great importance to me personally and has done immense good…I have seen a bit of the world and have acquired some experience… Now at any sort of meeting I can talk on a subject that most men would be eager to hear…’

As a mentor to Amar Singhji, Sir Pratap takes it upon himself to orchestrate Amar Singhji’s wedding to set an example among Rajput society and such a wedding he organizes as only Sir Pratap could. A staunch Arya Samaji, he shuns needless pomp and display and organizes the rituals according to basic Vedic tenets, but the wedding party must also be suitably distinguished as befitting his position as the regent of Jodhpur. The Barat comprised only of Amar Singhji’s brothers in arms of the Jodhpur Lancers. No dowry was accepted, in fact the bride’s family was not to spend a single rupee to entertain the Barat. They carried their own tents, food, wine and musicians and the only person to enter the brides home was the groom. The Jodhpur Lancers camped outside the fort at Satheen (The bride being the sister of the Thakur of Satheen, western Rajasthan) waiting for the marriage rituals to conclude and escort the newly-weds back to Jodhpur.

‘The village people had also come out in dense crowds but none of them could make out the bridegroom (who would normally be wearing showy clothes and riding a caparisoned horse) I was wearing just the same clothes as the others …Most of them thought that the bridegroom had not yet arrived…Best of all that there was no beating of Tomtoms or unnecessary noise caused by the singing of Dholis which is a thing I hate from the very bottom of my heart…’

The young 23 year old, married war veteran is invited to join the Imperial Cadet Corps in 1901, a military academy for young Indian Aristocrats set up by Lord Curzon to remedy the lack of a Native Officer Class in the Indian Army.

Tuesday, 14th June, 1904

…At six we had practical fortification and were taught how to make a gabion. This work was rather amusing…while we were making this gabion we had some coolies digging a trench. It is awfully hot nowadays so the commandant very kindly gets some other people to dig for us…Amanat Ullah Khan took a photo in which we sat on the fence choker and put the gabion on Khan’s body. The photo will be an awfully funny one.

In 1911 Amar Singhji was among the ICC Royal Horse Guard of the Viceroy Lord Curzon at the Delhi Durbar to celebrate the coronation of King Edward VII

‘All along the roads were lined with troops and as we trotted past the regiments saluted the king. I was in the very last section of the Cadet Corps and most of the companies raised their colours just in front of my horse and frightened him a lot. When we got near the amphitheatre and just as we entered the pace was reduced from a trot to a walk and we were able to see what a splendid gathering it was. We escorted the King to the Royal Shamiyana and then trotted out and afterwards marched in from the rear…The king finished his first speech then we marched up and took our seats in the rear and both sides of the throne…’

Lt. Amar Singhji graduates from the ICC with a commission signed by King Edward to be an officer in the Indian Native Land Forces. His first and longest assignment from 1905-1914 is as ADC to General O’Moore Creagh, GOC 5th Div Western Army Corps, Indian Army at Mhow. Serving as a staff officer did not raise the controversial question of a ‘black commanding a white’. On the 17th of August 1914 he receives a letter detailing him for active service and with an order to report to General Brunker commanding the 9th infantry brigade at Karachi. Captain Amar Singh joins the Indian Army on the western front, seeing active duty in France and Mesopotamia on the personal staff of General Officers Commanding the Sirhind Brigade of the Lahore Division.

Thursday, 8th April, 1915

A few notes about the severe fight at Neuve Chapelle …Later on in the afternoon our guns took up bombarding the German trenches to prepare the way for an attack…it was a most magnificent sight…over the enemy’s trenches there was one huge curtain of white and black smoke which seemed as if a big forest was on flames…after the appointed time of the shelling was over all the gunning stopped and we heard nothing but rifles and machines and then saw some of the infantry got out of their trenches and advanced by short rushes. All went well until a bullet hit the wall quite close to Morse’s face and a small brick splinters hitting him on the face drew blood…

Now a few words about the attack… the bombardment did not do much damage because the shells were falling a bit beyond the German trenches… they put the range up rather too quickly. The result was that the enemy remained in the trenches. Another thing was that our infantry ought to have moved out even while our guns were shooting and while the Germans did not put their heads up. There was about 500 yards of ground to be covered before we could reach the German trenches…the germans were able to meet us and simple mowed our men down with their machine guns. We suffered very badly and though we took some of the trenches we were finally stopped by a small stream. Our object was to gain a small forest…and in this we failed…we had no cook and ate mostly bread, butter and jam and sometimes a tinned thing. Everything that we touched was clammy and dirty…

Amar Singhji officially retired from the Indian Army on June 30th 1923, but the best years of his military career had just begun. Later that year General Sir Henry Watson visited Jaipur and included a trip to Kanota in his itinerary.

Tuesday, 3rd July, 1923

‘The General told me the Jaipur Army was going to be reorganized and asked me if they offered me the command of the Cavalry Regiment and the Artillery battery would I accept it? I said I would.’ Amar Singhji was the commandant of the Kacchawa horse also known as the Jaipur lancers from 1923 to his retirement as Major General of the Jaipur State Forces in 1936.

In 1927, when the Military adviser in Chief personally inspected the Jaipur Lancers, wrote the following report:

‘He (Amar Singhji) is well served by his officers who are up to the standard of the Indian Army. There has been a great improvement in the unit since it moved into new lines. I foresee that in a couple of years this unit is going to be first class. There is now an atmosphere of keenness throughout and a keen spirit. All that is required is an organized system of training and plenty of work in the field.’

Sunday 20th December 1931

Discipline is not maintained by harsh treatment and strictness only. The secret of success is that all ranks must not only be afraid of you but they must also love you. Fear and love ought to be combined in equal proportions.

A Rajput aristocrat, Edwardian Gentleman, the first Indian Officer in the British Indian Army and a war veteran, many lives and one man.

(All images are the copyright of the General Amar Singh Kanota Library and Museum Trust)