Conflict is not a new phenomenon to democratic societies. This is more so in India, with its large and diverse heterogeneous population comprising several distinct geographies, languages, religions and ethnicities, which increase vulnerability levels manifold. Economic and social disparities and governance deficits within the country further exacerbate such vulnerabilities. Consequently, India has faced multiple insurgencies in various parts of the country since independence. These include insurgencies in the Northeastern states, Jammu and Kashmir, Punjab as also in a vast swathe of territory, on the Eastern side of the country, stretching from West Bengal down to Telangana, which has been afflicted with Left Wing Extremism (LWE).

India’s record in dealing with internal armed conflict (insurgencies and terrorism, sometimes also referred to as low intensity conflict), has been a mixed one. It has never allowed the situation to escalate to a level of civil war, and it has never lost a counter insurgency campaign. However, the nation has successfully resolved conflict in only three of its counter insurgency campaigns—Mizoram, Tripura and Punjab. In all other cases, the insurgencies though contained, continue to persist, such as in Nagaland, Manipur, Assam, Arunachal Pradesh, J&K and in LWE affected districts, popularly called the Red Corridor. This indicates that while India has been successful at ‘conflict management,’ its record in ‘conflict resolution’ has not been of the same order, which in turn condemns its security forces to containing insurgencies and terrorism indefinitely, at great human and financial cost. With 2018 now being a part of history, analysis of data indicates that Violence levels have dipped in the northeastern parts of the country, but have remained fairly constant in the two states most affected by Naxal violence.

An analysis of violence in LWE affected states show a drop in violence levels in all but two states, but hopes of an early end to conflict do not appear on the horizon. Since 2004, violence levels escalated all across the affected areas, peaking in 2010 when LWE claimed 1180 lives, of which 626 were civilians and 277 were security forces personnel. During this period, 277 terrorists from various outfits, mostly from the CPI (Maoist) were eliminated. In 2011, violence levels came down to half of the 2010 figures and these were halved once again in 2012, but since then, there has been a remarkable resilience and tenacity on the part of various Maoist outfits in Chhattisgarh and Jharkhand to continue to inflict casualties on the security forces and to unarmed civilians, albeit on a smaller scale than in the period 2004-2012.

The geographical spread of areas affected by Maoist violence has however shrunk, with some of the earlier affected states like West Bengal, Kerala and Madhya Pradesh reporting zero incidents of violence in their affected districts. There has also been a dramatic decline in violence levels in the affected districts of Odisha, Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Bihar and Maharashtra, which together had but six SF fatalities and 32 civilian fatalities related to Maoist violence in 2018. During this period, in the above districts, terrorist casualties were reported as 72. Replying to a question in the Rajya Sabha on 14 March 2018, Shri Hansraj Gangaram Ahir, Minister of State in the Ministry of Home Affairs stated that 106 districts in 10 States are included in the Security Related Expenditure Scheme of the Government for Left Wing Extremism (LWE) affected States. He added that in 2017, only 58 districts in the country reported LWE violence. As per a senior Home Ministry official quoted by the Times of India, post a review carried out in the Ministry, the number of Naxal affected districts have been brought down to 90, of which 30 are the most affected. Of the 30 most affected districts, 13 are in Jharkhand, 8 in Chhattisgarh, 4 in Bihar, 2 in Odisha and 1 each in Andhra Pradesh, Telangana and Maharashtra.

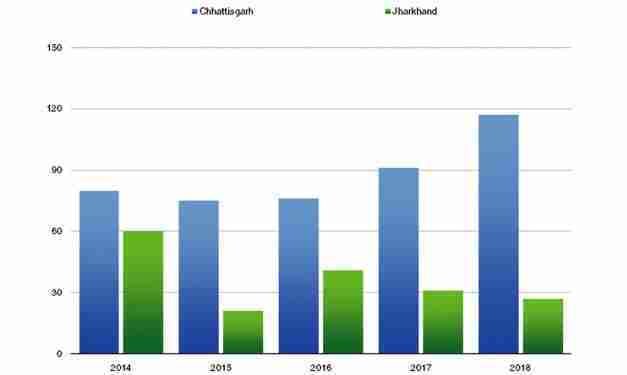

Development and security related measures undertaken by the concerned states has caused an improvement in the security environment and has led to a shrinkage of the areas under Maoist influence. Political penetration in areas which earlier were under Maoist control has also played a role in shrinking Maoist influence. However, in the two critical states of Chhattisgarh and Jharkhand, violence levels have not shown a declining trend (See Figure 1). This is the base area of the Naxals, which affords protection to the insurgents due to dense jungles, underdevelopment and paucity of roads and tracks, which makes movement difficult. In 2018, these two states accounted for 77 civilian fatalities and 67 SF fatalities, which in terms of SF fatalities was about 14 times and in terms of civilian fatalities, over half the number suffered in all other states combined. This is worrisome and gives rise to the possibility of a further expansion of Maoist activity into the neighbouring region, if left unchecked.

- Some of the major attacks that have been carried out by the Maoists against the security forces in 2018 are as under:

- 24 January: 4 SF personnel killed in Narayanpur district, Chhattisgarh.

- 13 March: 9 SF personnel of the Chhattisgarh Cobra Force killed in a land mine blast in Sukma district, Chhattisgarh.

- 20 May: 7 SF personnel killed in Dantewada district, Chhattisgarh.

- 26 June: 6 Jharkhand Jaguar Force personnel killed in land mine blast in the Chinjo area of Garhwa district.

- 11 July: CRPF constable killed in an attack in East Singhbhum district of Jharkhand.

- 27 October: 5 Central Reserve Police Force (CRPF) personnel killed and one injured after Maoists blew up their bulletproof bunker vehicle in Bijapur district, Chhattisgarh.

- 30 October: Doordarshan staffer and two SF personnel killed in a Maoist attack in Dantewada district, Chhattisgarh.

- 8 November: A soldier of the Central Industrial Security Force (CISF) and four civilians were killed when an improvised explosive device tore through a private bus in Dantewada district.

- 11 November: Maoists trigger 6 IED blasts in Kanker and attack a BSF patrol in Bijapur, killing a BSF sub inspector. The above attacks make it clear that the Maoists retain the ability to strike in their chosen areas against the police forces operating against them. The 27 October attack by the Maoists in Chhattisgarh which were followed by a few more attacks in November were an attempt to enforce a boycott of the polls. Despite threats of violence, the people came out and voted in large numbers in both phases of the polls on 12 and 20 November, which augurs well for the state and indicates that the support which the Maoists expected from the masses is not forthcoming.

Earlier, on 7 October, Home Minister Rajnath Singh, while addressing troops of the Rapid Action Force on their 26th anniversary in Lucknow, stated that the number of districts affected by Naxal violence has reduced to 10-12 districts from the earlier 126 affected districts and expressed optimism that Naxalism will be wiped out within three years. While one can laud the optimism of the Home Minister, the ground situation as of now does not point to an early end to conflict. It may take a decade or more to restore normalcy, depending on whether the respective states and the Centre musterthe requisite will to deal with the Naxalite leadership, especially their urban support base with a firm hand and at the same time, improve governance and justice delivery mechanisms, to restore confidence within the public to wean them away from the clutches of the terrorists.

State Response: Right Policies, Poor Implementation Mechanisms

The Centre’s efforts to deal with LWE is premised on a holistic approach, wherein security and development go hand in hand with ensuring rights and entitlements of local communities, improvement in governance and public perception management. Poverty alleviation programs are an important part of the focus of the state governments which are being assisted by the Centre. Legislation has also been enacted to protect tribal rights and interests. The approach is pragmatic and logically should have led to conflict resolution, especially as LWE, unlike the other festering insurgencies and terrorism within the country, is an indigenous movement which is not externally inspired, and even today has but limited support from external actors. If the policies are right, then obviously we need to look into why the Naxal movement continues to thrive.

One of the causative factors is the federal structure of the country, whereby law and order is a state subject and is not on the concurrent list of India’s Constitution. Interventions by the Centre in Maoist affected states can only be forthcoming if the affected state requests for assistance. However, once the Centre intervenes and provides assistance, the state governments dither on taking ownership of the problem and remain lackadaisical in building indigenous capacities. Another area of concern is that government departments, whether in the Centre or in the state, seldom ‘think, speak and act in concert,’ and as a result, there is a marked lack of unity in effort in all the agencies involved in countering the insurgent threat. There also is an apparent lack of political consensus between the elected representatives of the state and of those in the Centre, which inhibits political solutions from coming to fruition. A possible solution could be an amendment to the Constitution, whereby law and order could be placed on the concurrent list. This however will meet with tremendous resistance from the states, which would view it as an imposition by the Centre and an attempt to usurp the powers of the state governments.

One of the causative factors is the federal structure of the country, whereby law and order is a state subject and is not on the concurrent list of India’s Constitution. Interventions by the Centre in Maoist affected states can only be forthcoming if the affected state requests for assistance. However, once the Centre intervenes and provides assistance, the state governments dither on taking ownership of the problem and remain lackadaisical in building indigenous capacities. Another area of concern is that government departments, whether in the Centre or in the state, seldom ‘think, speak and act in concert,’ and as a result, there is a marked lack of unity in effort in all the agencies involved in countering the insurgent threat. There also is an apparent lack of political consensus between the elected representatives of the state and of those in the Centre, which inhibits political solutions from coming to fruition. A possible solution could be an amendment to the Constitution, whereby law and order could be placed on the concurrent list. This however will meet with tremendous resistance from the states, which would view it as an imposition by the Centre and an attempt to usurp the powers of the state governments.

Economic packages are at times thought to be the panacea for resolving insurgencies. There is certainly an element of economic deprivation which drives insurgencies, and development of the area must certainly be a key intervention to conflict resolution. The Centre has not been tardy in allocating resources to the affected states for boosting economic development, but the mere infusion of aid achieves little. Most states are unable to absorb the massive infusion of aid, but more importantly, poor financial oversight and lack of accountability result in its improper utilisation. In many cases, state funds have led to massive corruption, with part of the money also finding its way into the hands of the insurgents. The state administration needs to focus on the utilisation of such aid and its impact on the security situation. The Centre on its part must make further grants contingent on results being visible on the ground.

Another inhibiting factor is the fact that political parties also seek the assistance of the Maoists, when it comes to fighting elections. In the recent elections to the Chattisgarh Assembly, Mr Raj Babbar of the Congress called the Naxals ‘revolutionaries,’ a comment which was severely criticised by the Prime Minister and others. Earlier, in 2010, Mr Digvijay Singh had stated in response to a question in a TV interview on the Maoists that, “No one can defend their criminal activities. But they are not terrorists”. Policies thus get constrained when harder options need to be applied for conflict resolution, which once again reaffirms the need for a national political consensus on national security issues.

An area requiring attention is intelligence, training and leadership. Newspaper reports of the attacks that have taken place against the police forces invariably state that the Naxals were in large numbers, sometimes in the range of 300 to 400 fighters. This may well be a gross exaggeration, but even if the attacks were carried out by smaller numbers of 30 to 40 Maoists, it is difficult to comprehend why the police forces were unaware of their presence. The attack on a large CRPF party in April 2010 in Dantewada is a case in point. Here, a force of 300 or so Maoists attacked the CRPF company in the Mukrana forest, killing 76 personnel, 74 of whom were from the CRPF and two from the local police. That the police forces operating in the jungles were unaware of the presence of such large groups of insurgents in their immediate vicinity, points to serious shortcoming in operating methodology, especially in terms of patrolling, field craft, battle drills, and most importantly, their ability to operate by night. The area they can dominate thus gets restricted to the immediate vicinity of their post and makes them easy targets for the Maoists as and when they venture out. Another vital aspect pertains to leadership, which remains a weakness in the CAPF. Only through good leadership and effective training can area domination be achieved, which will put the Maoists on the back foot. This is not a facet which can be addressed through technology, such as the use of drones. Technology is a useful force multiplier, but in the absence of well trained and well led police forces, technology can have little impact on ground operations.

Efforts also need to be enhance to restrict insurgent money supply and availability of weapons and ammunition. Demonetisation did have a temporary effect, but the Maoists seem to have recovered from that shock. Maoist financial collections are assessed to be of the order of Rs 140 crore per annum, the sources being business establishments,industry, contractors, corrupt government officials and political leaders. The major part of Maoist revenue comes from the mining industry, PWD works, and collection of tendu leaves. Taxes are also levied by the Maoists in their strongholds and there is a symbiotic relationship between Maoists and illegal mining as well as forest produce. A large part of this amount comes from extortion, where paradoxically, all the actors get a share in the pie —the contractors, the Maoists and the public servants. Greater focus of the government in squeezing Maoist finances is necessary if the Maoist threat is to be neutralised. This must hence be a prime intervention of both the State and Central governments.

Left Wing Extremism draws sustenance through espousal of their ideology, which runs counter to the idea of Indian democracy. The conflict in India’s heartland is thus a battle between democracy and all that it stands for versus a dictatorship involving the suppression of the very freedoms democracy believes in. For democracy to win this battle, it must be perceived to be a functional and worthwhile entity. This would require a visible and effective justice delivery mechanism to the poorest in India’s heartland, transparency in governance, empathy on the part of government officials and targeted socio economic development. However, many of the lower level functionaries of the state, who interact with the locals—like the forest guard and the local constable, to name but a few— are themselves perceived by the tribals and other deprived sections of society to be agents of suppression and exploitation. There is thus a need for greater empathy from all government agencies. Good governance and an effective justice delivery mechanism are also key issues that need to be addressed.

The Naxal challenge primarily remains that of development, governance and rights delivery. Today, we need to provide good governance in the worst of law and order environments. To that purpose, a better civil administration structure would need to be created in place of the model we presently have. This could draw upon the best officers from across the country, as a replacement of the Indian Administrative Service (IAS) in the LWE affected areas. This could be constituted on the lines of the former Indian Frontier Administrative Service (IFAS), which unfortunately was merged into the IAS.

Conclusion

The attention of the government is focussed on a holistic approach to combat Left Wing Extremism, but the Indian State still suffers from feudal mindsets, mis-governance and corruption. Solutions lie in proper implementation of the various initiatives taken by the government to address the concern of the tribal population and the marginalised sections of the population living in India’s heartland. In the absence of improvement in governance mechanisms, the cycles of violence and counter violence will continue indefinitely, which will retard India’s progress in becoming a strong regional and global player. It is difficult to fault the approach of both the Centre and the States. What needs to be addressed are the mechanisms to implement the governments intent.

In terms of a whole of government approach, the government must function within the ambit of law and ensure that Constitutional safeguards to the tribal population are protected and enforced, in letter and spirit. In terms of governance capacities, the institutions of the state must be resurrected and made effective, to include justice delivery mechanisms and an effective civil administration. The whole of government approach must involve all instruments of state power—political, diplomatic, economic, social, administrative and military in a holistic manner and ensure unity of effort. And finally, the government must mobilise the population through an effective perception management campaign. For the police forces operating in the area, a cardinal principle must be to win the faith and trust of the local population through empathy and focussed intelligence based operations. This is not an easy ask—but this is the only way to ensure that this long running insurgency in India’s heartland becomes a thing of the past.