Current Iran-US relations are a very fascinating subject of study among scholars in international affairs. Many works, during the last few years, have been contributed to study various aspects of this relationship. But very few attempts have been made to understand this relationship in a historical context. The belief that history necessarily is not absolutely important in understanding the problems in Iran-US relationship overlooks the crucial point that an imbalance in historical knowledge is not a small problem either. The past explains the present better and hence an attempt is made to relate history to the current context.

Modern Iran was a victim of the Great Game played between the USSR and Great Britain which were making constant infringements on both of its northern and southern flanks. Iran was discovering ways to insulate it against the two European powers. During the Second World War, when the US appeared in the international scene as a major global player, Iranians perceived it as a protector against both the Soviet and the British encroachments.

Iran and the Cold War

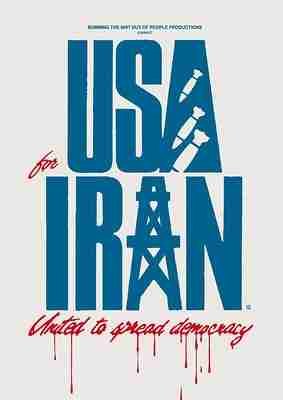

American interest in Iran, during the Cold War, was focused on two major points one was to checkmate the rising influence of Soviet Union and second, to exploit the abundance of oil as cheap energy. Hence the US started to assist it in economic, political, military and even nuclear affairs.

A report published in Times, 1961 made the following assessment: During the previous decade, roughly since 1952, the American grants and loans in several forms to Iran have totalled about $1,135 million. Of this, about $631 million has been for economic assistance and $504 million for military assistance. It started the much-aspired nuclear programme in 1957 with a boost from the Eisenhower Administration and by 1970 the Shah approved plans from the US to construct 23 nuclear reactors which would be completed by 2000.

This warm relationship got a new boost after the United Kingdom’s withdrawal from the Persian Gulf region in 1973 which created a vacuum that required a further strengthening of US alliances. The US started to follow a twin-pillar policy that relied heavily on Iran and to a lesser extent on Saudi Arabia to control the region. It was often said that President Nixon, in 1973, personally had asked the Shah to protect him and approved a blank cheque (the opportunity to buy everything short of nuclear weapons).

The Shah had exploited the situation and his demands started increasing day by day. From a mere tripwire for triggering the American retaliation against Soviet aggression, it became an actual bulwark against Soviet surrogates in the area. Relations between the two nations, reached its apex. By 1979, this resulted in a 600 per cent increase in Iran’s military expenditure and a 10-fold increase in US military sales to them.

The backlash came with the Islamic Revolution led by Ayatollah Khomeini in 1979. Besides overthrowing the US-friendly Shah, the Ayatollah’s followers promptly took American diplomats in Tehran hostage for 444 days. It was a watershed in US-Iranian relations. The hostage crisis did not make Americans any more sympathetic to Iranians. It left an indelible imprint of hatred in their minds though the Americans claim themselves as serial amnesiacs.

The shift

The American policy soon found a major shift in its foreign policy approach. In the Iraq-Iran War that continued from 1980 to 1988, the Americans supported Saddam Hussein in all possible ways. By the late 1980s, the US was playing an increasingly proactive role in its protection of shipping in the Persian Gulf. While Iranians were similarly concerned with the regular flow of oil out of the Persian Gulf. Iraq sought to block these exports. Iranian retaliation focused on the oil exports of Gulf littoral states that were financing the Iraqi state. Now that the US was protecting these states, Iran and the US found themselves in direct confrontation.

During the twilight years of the war, the US Navy opened up a second front against Iran, drawing the country’s limited naval resources away from any supporting role along the Shatt al Arab waterway. Subsequently, in the 1990s and also in the early part of this century, the US followed a policy of dual containment policy against Iran and to a lesser extent against Iraq and classified the former as a rogue state.

During the last one decade, it had been accused of playing an opposite role against the US in the War on Terror, a destabilising role in Afghanistan and a nuclear-weapon programme that threatens not only the US but also its allies in the Gulf region. Highs and lows of this tumultuous relationship, as has been witnessed in recent years, are only part of the story.

Beyond the rhetoric and usual American recriminations, an intriguing picture of a superpower’s struggle to craft and implement a viable, coherent and dominant foreign and energy policy is hidden.

Beyond the rhetoric and usual American recriminations, an intriguing picture of a superpower’s struggle to craft and implement a viable, coherent and dominant foreign and energy policy is hidden. Policymakers of the US, no doubt, know a lot about Iran. But at the end of three decades, since the Islamic Republic was put in place, key players are still lamenting about how little the US understood Iran. Something arguably had badly gone wrong and should have been addressed more proactively.

Not only the US policymakers have gone fundamentally wrong, but the Iranian hardliners are also committing grave mistakes. Iran’s economy is shabby and needs to be globalised. The most important energy sector is highly redundant and requires a thorough renovation. Without assistance from the US, it is simply not possible. The US, on its part, needs Iran for bringing stability in both Afghanistan and Iraq. Without the help of Iran, it seems less likely at this stage. Hence an Iran-US rapprochement will help the US in those counts. India, having a huge national interest in both the countries, will be one of the greatest beneficiaries.

— The author holds a Ph.D from the Jawaharlal Nehru University on West Asian studies and specialises on Persian Gulf Affairs